Welcome to the 152nd Pari Passu Newsletter.

After two deep dives into healthcare with Bausch and Better Health, it’s time to return to where restructurings run deep: retail.

Earlier in June, we explored the case of Tupperware, a food container company whose dependence on direct selling lost relevance as consumers shifted towards online retail. Today, we are looking at another storage brand that also failed to adapt to changing consumer preferences: The Container Store.

The Container Store pioneered storage and organization solutions for households. However, its reliance on an in-store shopping model and the commoditized nature of its products left it vulnerable as consumers increasingly preferred online retail. Through The Container Store’s bankruptcy, we will understand how the failure to adapt business model and liquidity strain ultimately led to its distress.

But first, a note on 9fin — the new official partner of the Pari Passu newsletter!

Hi guys, I’m so excited to announce that the Pari Pasu Newsletter has officially partnered with 9fin.

I first got onto 9fin early in the year, and it’s been a complete game-changer for both my investing and writing process. It's incredibly easy to use: within seconds, I can pull up a complete set of relevant news, data, and sophisticated analysis on any situation I'm tracking. In a short time, it's become my go-to platform for quickly making sense of what are often very complex restructurings (and to make sure I do not miss anything relevant!).

Fast-moving and opaque situations, like First Brands, are 9fin's bread and butter. They consistently post scoops and detailed analyses that help break down the nuanced detail of what's happening.

For example, last week, 9fin was first to report that Apollo had gained access to information on part of First Brands’ off-balance sheet funding before scrutiny of the auto parts supplier's financing arrangements clouded its future.

This is exactly the edge 9fin provides. They are clearly differentiated by the speed and quality of information they deliver. In my time on the platform, I’ve seen their editorial team being able to get previously unattainable levels of intel. And it's not just the journalism, the data screeners, and integrated court filings have genuinely collapsed what used to take hours pulling data and research across multiple platforms into one place.

Over the coming issues, 9fin will be bringing you exclusive content, webinars, events and offers. And to start with, I’m extremely excited to share that 9fin is offering Pari Passu readers a 45-day free trial, 15 days longer than usual.

Click below to learn more, and to access your free trial.

Even if you are not interested in their services now, I would check out their page as they have a lot of educational write-ups just like this one.

Huge thank you to 9fin for enabling the growth of the Pari Passu Newsletter!

The Container Store Overview

Founded in 1978, The Container Store (TCS) is a pure play retailer providing premium storage and organization solutions. The company positions itself in the higher end of the market by offering both standardized organization products and highly customized solutions [1]. Its product assortment includes standard organization items such as clothes hangers, shoe organizers, and modular drawers (generally priced between $10 and $25), to premium custom closets through its Elfa line (pricing ranges from $100 to $10,000) [2]. Approximately 50% of sales come from private label or proprietary products that are exclusive to TCS, reinforcing its brand differentiation and product exclusivity [3].

Figure 1: Select TCS Kitchen and Storage Products

The Container Store’s branding emphasizes its role as a premium provider of home organization, catering primarily to affluent households seeking tailored, design oriented storage solutions. This premium positioning is supported by its customized product offerings, strong customer service model, and selective approach to store expansion. The company typically operates in A+ real estate locations in affluent trade areas [1]. As of September 2024, TCS operates 102 stores across 34 states, with an average store size of approximately 24,000 square feet (or 18,000 selling square feet) [4].

Founding History

In the 1970s, storage and organization did not exist as a retail category. Manufacturers only supplied corrugated and other storage products for industrial or commercial applications, rather than for household use. At this time, if consumers wanted to get boxes for personal use, they would have to find used ones from the back rooms of grocery or department stores. While small plastic products such as Tupperware were already on the market for consumers, large scale plastic containers were not an available option for consumers. Larger plastic boxes were fragile and lacked the durability and design needed for household organization. The idea of a dedicated retail use for storage and organization solutions was, at the time, unheard of.

Kip Tindell, a recent college graduate, Garrett Boone, a master’s student, and architect John Mullen recognized this gap in the market and saw an opportunity. They believed that American households needed practical, affordable, and attractive ways to organize their belongings, reduce clutter, and save time in daily life. In 1978, the three partners opened the first Container Store in Dallas, Texas. The store’s initial assortment included a wide mix of products, such as milk bottle crates, Metro shelving, wicker baskets, and Lucite canisters, which had previously never been available to consumers at traditional retailers. The concept quickly gained traction: within two weeks of opening, the store was thriving, fueled by word of mouth recommendations that spread quickly throughout the neighborhood [5]. The Container Store’s debut effectively marked the creation of storage and organization as a retail category, and the company remains the only pure play retailer of organizational products in the United States today.

Following its early success, The Container Store entered a period of rapid growth throughout the 1980s and 1990s. They opened new stores in other states such as Georgia, Illinois, and Colorado, with each expansion reinforcing the company’s ability to scale its operations. The Houston store opening, for example, received customer demand three to four times higher than what the founding team had anticipated [5]. This overwhelming response affirmed the receptivity to the company’s founding concept, and the scaling of operations laid the foundation for The Container Store’s core operating principles.

In this period, The Container Store began to shape its branding as more than just a seller of organizational items. The company cultivated its branding as a problem solving retailer, offering not just products but rather a way for customers to be in control of their lives, save time, and reduce stress through thoughtful organization. This brand promise was reinforced by the company’s highly trained sales staff. Employees were encouraged to spend a lot of time with customers, often sitting down to design tailored storage solutions that addressed individual household needs. The combination of curated product mix and customer centric service distinguished The Container Store and positioned it firmly in the premium segment.

In 1999, The Container Store acquired Elfa International AB, a Swedish manufacturer of wire drawer and shelving systems, which had been the most successful product line since the company’s founding [6]. The acquisition gave The Container Store control over a critical supplier and secured access to one of its most differentiated product categories. The Elfa brand quickly became and remains synonymous with the company’s customized closet offerings today.

In July 2007, the private equity firm Leonard Green & Partners acquired a majority stake in The Container Store, providing external capital to support the continuous scaling of the business [7]. Terms of the deal were not disclosed. Six years later, in 2013, the company completed an initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange at 12.5mm shares and an offering price between $17 and $18, representing a $827mm valuation. They ultimately raised $225mm, constituting a 27% stake, with Leonard Green & Partners retaining a controlling interest. This interest continued until 2021, when LGP reduced their ownership below 50% [8].

Business Model

The Container Store operates a dual-channel business model across physical retail stores and e-commerce platforms. While online sales have become increasingly important in recent years, the company’s model is still deeply rooted in its in store experience, given that sales associates play a central role in designing and selling customized storage solutions. The Container Store generates revenue across two primary operating segments:

The Container Store Segment (95% of revenue): encompasses both custom spaces and general merchandise. Custom spaces include fully owned and manufactured shelving systems and wood and metal based organization products. These are tailored to customer demands for specific areas of the home such as closets, kitchens, garages, and bathrooms. These products are often sold as complete projects with installation services. Some Elfa products are also sold in this segment. On the other hand, general merchandise consists of more standardized organizational products, spanning over ten thousand items. These products include categories such as bins, baskets, drawers, and modular storage systems.

Elfa Segment (5% of revenue): Elfa designs and manufactures component based shelving and drawer systems, as well as sliding doors, which are then sold through The Container Store segment in the United States. Its products are highly customizable and are used across closets, kitchens, offices, garages, and other areas of the home. While The Container Store is Elfa’s exclusive distributor in the U.S., Elfa products are also sold through other retailers in approximately 30 countries, with a concentration in Northern Europe.

Despite The Container Store launching their website in 2000 and recent initiatives to grow online sales, only 28% of FY 2023 revenue was generated online, with the rest still coming from physical stores [3]. Peers to The Container Store vary widely in their online versus physical store sales mix. For example, Home Depot generates 10% of sales online and IKEA generates 26%, whereas Williams-Sonoma generates 66%. This reflects the company’s long standing emphasis on in person customer service and key value propositions being tied to its in store experience. As a result, customer loyalty is high, with the average customer having a fifteen year tenure with the company. The company’s 102 stores are positioned in urban centers where there is strong demand for home projects and customizations.

Figure 2: Geographic Map of The Container Store’s Asset Network

Employee Programs

Supporting this focus on personalized in store experience, The Container Store invests heavily in employee training and development. The company employs 3,800 people, 2,900 of which work in store locations [4]. Full-time employees receive over 200 hours of training in customer service, compared to the low to mid double digit training hours typical in retail [5]. This extensive preparation allows associates across different stores to deliver consistent recommendations for customer projects, reinforcing the company’s reputation for expertise and reliability.

The company further differentiates itself by offering wages nearly double the retail industry average. In addition, The Container Store has historically sought to align employee incentives with ownership. Its 2013 IPO was driven in large part by a desire to give equity to employees. At the time of the offering, the company implemented a direct to share program through which employees received a 14% equity stake, which is far above the typical 2% allocation [5]. These initiatives have helped the company maintain an annual employee turnover rate of less than 10%, compared to an industry average closer to 30%. However, these practices also contribute to structurally higher SG&A expenses, which account for more than 50% of revenue [4].

Supply Chain and Vendors

Another unique aspect of The Container Store’s business model is its supplier network. Despite the fact that the company does not maintain long term contracts with vendors, most of their vendor relations are very long standing. Notably, eighteen of its top 20 vendors have supplied products for at least ten years, and many of these relationships are exclusive to The Container Store. These long standing arrangements are partially rooted in the company’s founding years, when Kip Tindell and his partners had to personally convince manufacturers to supply their industrial and commercial products to them for retail use. By educating suppliers on the differences in consumer facing sales and negotiating favorable terms, the founders built trust and established partnerships that remain central to the business today [9].

From a geographic perspective, The Container Store sources approximately 47% of its products domestically and 53% internationally, with around one third of imported goods coming from China [4]. All products flow through one of the company’s two distribution centers, which manage both retail inventory and direct to consumer order fulfillment. In addition, the company operates its own manufacturing facility in Illinois (known as C Studio), which produces wood based custom space offerings.

Path to Distress

The broader changes in consumer retail habits and the growing competitiveness of the storage and organization category laid the foundation for The Container Store’s recent struggles. Beginning in the mid 2010s, the retail environment shifted significantly. American consumers began to redefine what they considered to be good customer service. Surveys showed that many cited Amazon as delivering strong customer experience, despite the lack of any direct human interaction. This stood in contrast to The Container Store’s model: the average customer drove around 25 minutes to reach a store, and sales associates were expected to spend significant time in conversation with each shopper to recommend personalized solutions. Consumers increasingly favored retailers where purchases could be completed in minutes and shipped directly to their homes, reducing the perceived value of The Container Store’s in-person expertise. As a result, the company began to lose customers making smaller purchases, typically items under $25, to diversified retailers that offered faster and more convenient alternatives.

A second challenge was the highly commoditized nature of The Container Store’s product set. While the company had pioneered the specialty storage and organization category, its standard organizational items were highly replicable, leaving little protection or sustainable moat from competitors. Major retailers such as Target, Home Depot, Williams Sonoma, and IKEA increasingly captured market share by offering comparable products, often at lower prices, with greater convenience and faster delivery. In a 2024 interview, The Container Store’s founder acknowledged that even when customers discovered products at The Container Store, they could frequently find similar items on Amazon or at other large scale retailers and have them delivered directly to their homes [5]. These competitors also benefited from streamlining SKUs, focusing on high turnover products, and minimizing inventory complexity. In contrast, The Container Store’s value proposition required maintaining a comprehensive and diverse inventory, which contributed to elevated SG&A costs and historically necessitated significant inventory build up ahead of key holiday periods.

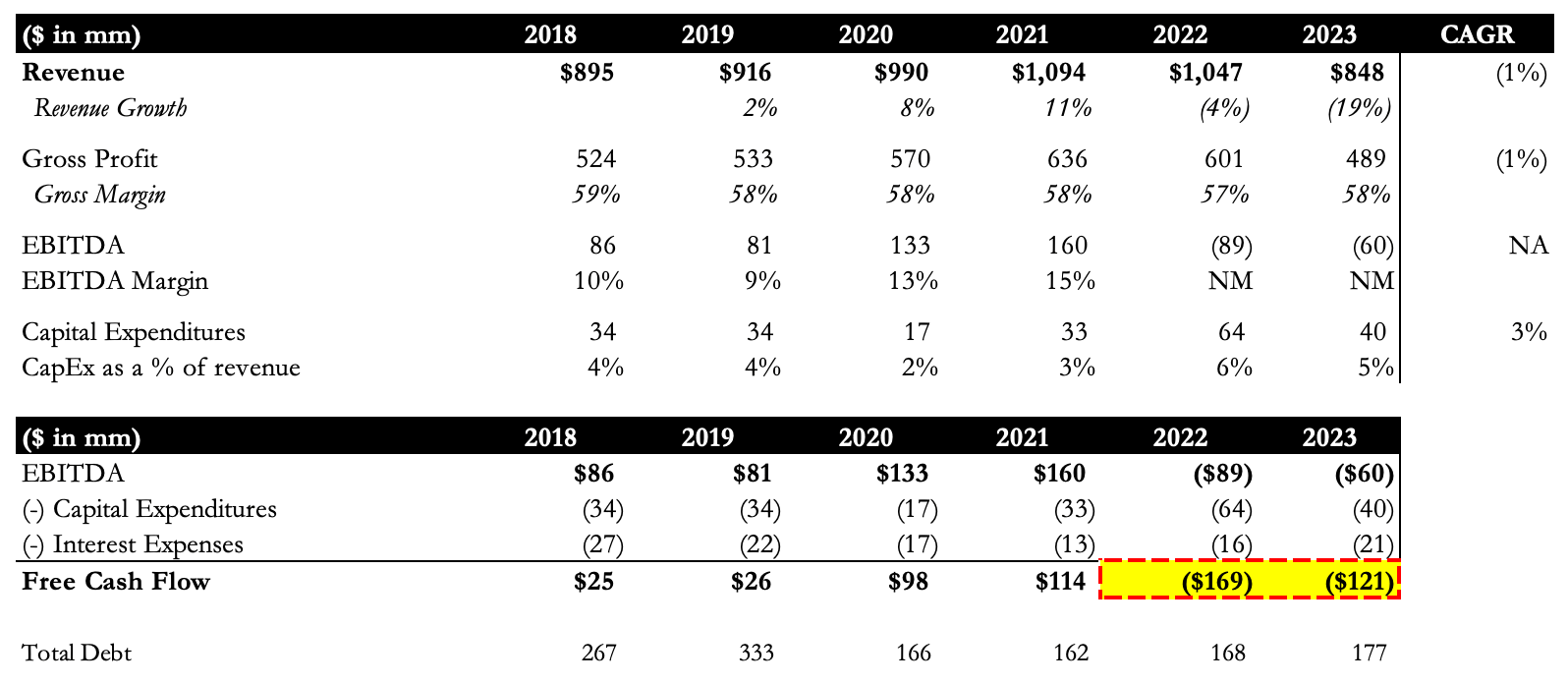

The combination of shifting consumer preferences and commoditized products began to materially weaken financial performance post-pandemic. While COVID-19 was a strong tailwind that made The Container Store’s performance peak in 2021, much of this demand was pulled forward, leaving a weaker post-pandemic retail environment. With fewer home sales, greater price sensitivity, and availability of similar products from mass retailers, consumer receptivity to The Container Store’s premium positioning declined. As a result, free cash flow quickly turned negative at ($169mm), and ($121mm) for 2022 and 2023 respectively [10].

Figure 3: Historical Financials

On top of operational challenges and negative cash flow generation…

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Full Access to Over 300,000 Words of Evergreen Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Access to the Restructuring Drive