Welcome to the 151st Pari Passu newsletter.

In today’s edition, we’re looking at Better Health Group, a Medicare-focused primary care platform backed by Kinderhook Industries. Better Health was one of the fastest-growing physician practice rollups in the Southeastern US Medicare-Advantage market. Today’s piece will cover how a modest change in Medicare policy had an outsized impact on Better Health’s liquidity and forced the company to pursue a first-of-its-kind liability management exercise.

Better Health serves as one of the most exciting LME cases of 2025, as the company was weeks away from closing its uptier transaction when the Fifth Circuit ruled that its methodology was no longer viable. Desperate for liquidity, instead of filing for Chapter 11, Better Health and its advisors scrambled from the original uptier to a brand-new extend-and-exchange transaction framework in just a few weeks.

Today, we’ll walk through the company’s history and liquidity challenges, along with the originally proposed LME and rapid pivot to a new transaction model. Lastly, we’ll end with the surprising outcome for a small lender group that challenged the deal, and analyze how it shaped recoveries across the capital structure.

Recent LME editions: Bausch, Quest, American Tire Distributors, Saks Global

Better Health

Physician Partners, more commonly known as Better Health Group, is a primary care provider founded in 2006 and headquartered in Tampa, Florida. Better Health operates as a managed service organization (MSO) and is built around the fast-growing Medicare Advantage market [1]. Medicare Advantage is a private version of Medicare, a government health insurance program for individuals aged 65 and over. Under Medicare Advantage, the government (more specifically, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)) pays insurers a fixed monthly amount for each senior, adjusted based on the patient's health status. For example, a healthy 65-year-old might earn the insurer $900 per month, while an 85-year-old with a pre-existing condition earns the insurer $2,000+ per month. These rates are determined by the CMS using a risk scoring system and are subject to change, which will become important later on. Medicare Advantage insurers typically charge patients the standard Medicare monthly premium of ~$175; however, low-income patients who qualify as dual eligible for Medicaid may pay no premium at all.

As an MSO, Better Health acquires physician practices, often independent clinics, and provides them with various services, including back-office support, revenue cycle management, marketing, etc [1]. The providers (physicians) keep delivering patient care at their clinics, but now as a part of Better Health’s platform, which handles the administrative and insurance-facing complexities. Better Health also provides the option for providers to retain ownership of their clinic, becoming a “strategic partner” [1]. This dual model allowed the company to expand by targeting both retiring doctors seeking an exit and to younger providers looking for support to scale their clinics.

From 2006 to 2019, the company operated as a founder/physician-owned business, primarily targeting Medicare Advantage-eligible clinics in the Southeast US. In 2019, private equity firm Kinderhook Industries acquired a majority stake in Physician Partners and rebranded it as Better Health Group [2]. At the time, the Medicare Advantage market was extremely fragmented, and Kinderhook would take advantage of this to rapidly expand via a rollup strategy. While financial details of the 2019 acquisition were not disclosed, Kinderhook would later make a $500mm equity investment in December 2021 to support continued clinic acquisitions. At the time of the 2021 capital infusion, Better Health had grown to serve over 137,000 members through a network of more than 545 providers (actual physicians and clinicians, not clinics themselves) [2]. Assuming 3-5 providers per clinic, the number of clinics under the Better Health umbrella likely ranged from around 100 to 200.

Figure 1: Better Health’s Value Proposition [1]

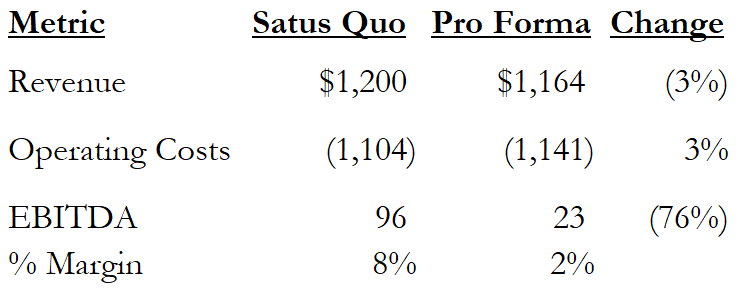

In November 2023, Better Health raised an additional $175mm in growth capital from its sponsor. While Better Health was and remains a private company, the press release provided some important details. First, the company had expanded to over 1,200 affiliated providers and over 250,000 patients, more than doubling both figures from the time of the 2021 $500mm follow-on investment [3]. Better Health also generated $1.2bn in annual revenue at the time. Additionally, later 9fin coverage reports a H1 2023 EBITDA margin of 8%. This equates to EBITDA of ~$96mm, providing an important perspective into the company’s financial health as of 2023 [6].

Liquidity Headwinds

While Better Health’s growth looked impressive by late 2023, the company’s profitability hinged on a critical variable: the Medicare Advantage program. Specifically, Better Health’s topline was almost entirely dependent on payments from Medicare Advantage insurers. While Better Health’s capitated payments (the per-member-per-month payments received from Medicare Advantage insurers) as a specific percentage of revenue are not publicly available, a similar company, Cano Health, reported capitated payments at 95%+ of revenue, highlighting the importance of these payments [11]. As a reminder, these reimbursement payments are determined by the CMS risk adjustment system, which assigns a risk adjustment factor (RAF) score to each patient based on age and diagnoses via a system known as hierarchical condition category (HCC) coding. The higher the score, the higher the per-member-per-month payment that’s downstreamed to Better Health. This system is designed to compensate providers for treating sicker populations.

In 2023, CMS finalized the transition to its updated risk scoring model, HCC Version 28, which would be phased in over the next three years from 2024 to 2026 [4]. The model added new HCC categories while eliminating thousands of others. This change resulted in a broad downward adjustment in risk scores, particularly for common chronic conditions such as diabetes, vascular disease, and depression. For Medicare Advantage providers like Better Health, this downward change in scoring meant they’d receive less reimbursement per patient per month, despite the cost of care remaining the same. Specifically, the change to Version 28 was expected to decrease risk-adjusted reimbursement rates by 3%, directly affecting Better Health’s topline [7].

While a 3% drop in revenue may seem modest, it’s important to consider that this occurred amid no changes to Better Health’s overall cost structure. Since primary care providers already operate at very slim margins, the impact of this change was disproportionately significant. By late 2024, it was reported that the company’s EBITDA margin had dropped from 8% to 2%, highlighting how the reimbursement changes flow directly to the bottom line [6]. However, as the analysis below shows, for Better Health’s EBITDA margin to drop by the reported levels above, the company must have also experienced a moderate increase in operating costs. While the driver of these increased costs isn’t publicly known, it is likely due to increased staffing costs amidst a widespread labor shortage affecting the broader healthcare industry [12].

Figure 2: Estimated EBITDA

While specific details of Better Health’s cash position aren’t public, it was reported that the company was burning ~$90mm annually [7]. This is reflective of three factors: the drop in EBITDA due to reimbursement changes, a disproportionately high interest burden, and continued clinic capex.

In terms of interest, Better Health’s funded debt consisted of a $750mm Term Loan B at SOFR + 5.50% due October 2028 [7]. Assuming SOFR of 4.5% as of Q4 2024, Better Health’s effective interest rate was 10%, equating to an interest burden of $75mm, more than triple EBITDA. Interest alone results in cash burn of $52mm. It is reasonably inferable that the remaining $38mm of cash burn ($90mm reported - $52mm), representing 3% of revenue, came from the company’s continued investment into new clinics. For context, the company opened or acquired 70 clinics in 2023 [7]. This equates to ~$540,000k capex per clinic, which makes sense given roughly 3-5 providers per clinic and the nature of Medicare Advantage clinical care, which doesn’t require surgery suites or expensive equipment.

Again, while Better Health’s true liquidity runway was unknown, we know that the company secured an additional $175mm of equity financing in November 2023. Assuming Better Health entered 2024 with $125-175mm of available cash, at the annualized cash burn rate of $90mm, the company would likely run out of cash in mid-2025.

As lenders took notice of Better Health’s increasing cash burn, the company’s debt began trading at distressed levels. In August of 2024, as Better Health’s term loan traded in the 60s, the company hired Evercore and Kirkland & Ellis as investment banker and legal counsel, respectively, to begin addressing concerns [7]. At the same time, a majority group of lenders retained Houlian Lokey and Davis Polk. The rest of 2024 marked a steady decline, as liquidity continued to erode with no real operational turnaround being executed. By December 2024, as Better Health continued to burn cash, its debt traded near 40 cents, setting the stage for the January 2025 LME [7].

Uptier Review

Before we dive into Better Health’s unprecedented transaction, it’s important to briefly review some of the important mechanics at play. We’ll quickly cover the structure of uptier transactions and the recent 5th Circuit ruling on the 2020 Serta Simmons transaction. If you are already familiar with these concepts (some of which were featured in our Quest Software writeup), feel free to skip past this section, as we’ll keep it largely high-level.

Uptier Structure:

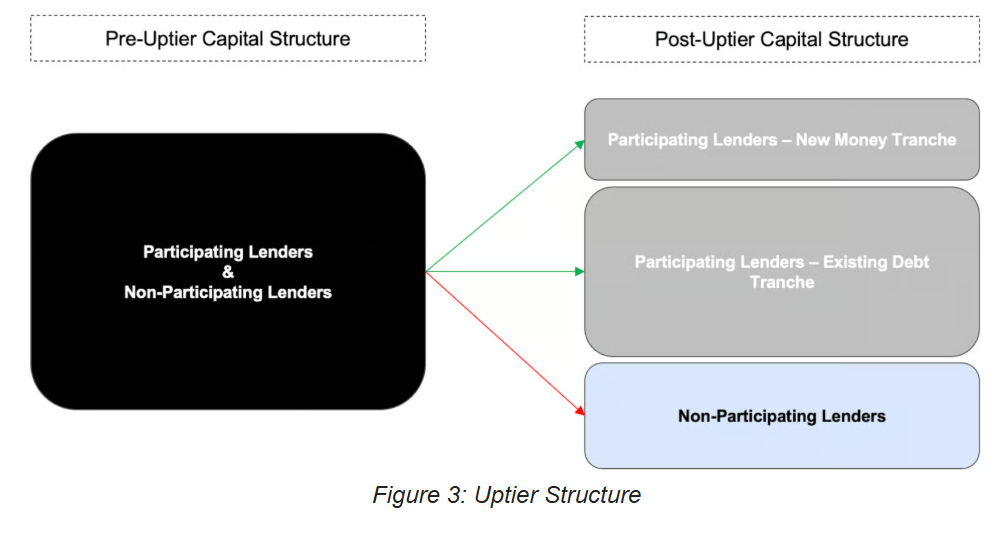

An uptier transaction involves amending an existing credit agreement (with majority-lender consent) to allow the borrower to issue new priming debt that sits above the old debt, often referred to as a “super senior” tranche. Participating lenders fund that new money, and are also invited to exchange their existing debt (at a discount or dollar-for-dollar) for a second-out tranche of priming debt. In an uptier, non-participating lenders are left subordinated to these new tranches, thus receiving a worse recovery in a bankruptcy scenario. The figure below visually depicts this type of transaction:

Figure 3: Uptier Structure

Serta Simmons Review:

Uptiers have been heavily litigated in recent years, the most notable of which is Serta Simmons’ June 2020 uptier. We’ve discussed this transaction in depth, but to quickly recap, Serta raised $200mm of new money via a non-pro rata uptier. Participating lenders (Eaton Vance, Invesco, etc.) exchanged $1.2bn into an $875mm second-out tranche, while providing $200mm of new money for a first-out tranche. While a third tranche was created, it was never used. Non-participating lenders were left with just over $1bn of now-subordinated debt.

To effectuate this transaction, Serta relied on an exception to the pro-rata sharing provision of its credit agreement, specifically allowing for non-pro-rata purchase of debt via an open market purchase (OMP). As a reminder, pro-rata sharing means that all recoveries/payments should be made equal to all lenders in a class of debt. However, without getting too far into the details, know that Serta used the ambiguity of this open market purchase definition to push through its transaction.

Fast forward five years, to December 31, 2024, when the Fifth Circuit of Appeals overturned a previous ruling upholding this transaction, which shifted the landscape of uptiers and LMEs more broadly. Borrowers, who now must move beyond the OMP exemption, have been forced to find new, creative ways to effectuate uptiers, which leads us to today’s transaction.

The Original LME

By December 2024, shortly before the Serta ruling, Better Health and its advisors had decided that a non-pro rata uptier was the best course of action for the company. Similar to Serta, Better Health’s credit agreement featured an open market purchase exception to its pro-rata sharing provision. In December 2024, as the company and the AHG (64% of TLB debt) prepared to execute the non-pro rata deal, a minority creditor group (18% of TLB debt held by two lenders), referred to as the “Priority Group,” retained White & Case as legal counsel and challenged the deal to receive better terms [7]. The remaining holdout lenders also comprised 18% of debt.

By year-end, Better Health, the AHG, and the Priority Group had settled on a non-pro rata uptier, summarized by the image below, that featured the following terms [7]:

$113mm in new money provided pro rata by all participating lenders

AHG exchanges at par into $162mm of first-out debt and $308mm of second-out debt

Priority Group exchanges at 80 cents into $65mm of second-out debt and $39mm of third-out debt

All remaining holdouts (~18% of debt) are offered an exchange at 70 cents into $67.5mm of second-out and $67.5mm of third-out debt.

Figure 4: Structure of Better Health’s Proposed Uptier (Note: Includes Pari Passu Assumptions)

The proposed LME included a couple of interesting features. The first was the way…

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Full Access to Over 300,000 Words of Evergreen Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Access to the Restructuring Drive