Welcome to the 135th Pari Passu Newsletter.

Two weeks ago, we explored the case of BurgerFi, a fast-casual chain whose aggressive acquisition strategy and premium positioning left it unable to cater to shifting consumer habits. Today, we will dive into another brand whose downfall also stemmed a failure to adapt to shifting consumer demands: Tupperware.

Tupperware became a household name in postwar America, revolutionizing food storage through direct-selling and iconic marketing. However, its heavy reliance on a traditional sales model left the company vulnerable as consumer behaviors shifted toward digital and omnichannel retail. Today, we’re going to dive into Tupperware’s bankruptcy and use it as a case study to understand how business model rigidity, liquidity strain, and creditor dynamics led to its downfall.

A Message From Restructuring

First, a quick message from me, Rx.

Over the last few months, we have been working really hard to develop the premium side of the newsletter. Tuesday’s article about Apollo’s Hunter-gatherer LMT was one of the most shared, go check it out if you have missed it earlier on the week.

On the other hand, I have had less time to dedicate to sponsors. If you / your company are looking to reach 22,000+ readers working in finance (with a strong interest in restructuring), please complete the form here and I will share my details from there.

Now, time to enjoy the writeup!

Tupperware Founding

During World War II, plastics were primarily used for military applications such as producing gas masks and various wartime equipment. After the war, the plastics industry faced excess production capacity from manufacturing military goods. Earl Tupper took advantage of this surplus and took plastic to the consumer goods market. Traditional polyethylene plastics were hard, smelly, and unappealing to everyday consumers, so Tupper experimented until he developed a cleaner, translucent, and more versatile material; Tupper Plastics was thus founded in 1938. His breakthrough came not just from the material itself, but from creating an innovative sealing mechanism coined the “Tupper seal.” Borrowing the concept from paint can lids, Tupper designed an airtight lid that made a burping sound when it was fully sealed. This feature was central to the 1946 debut of the Wonder Bowl and a line of companion storage containers that marked the beginning of the Tupperware brand.

Tupperware products gained traction during a time when American families were seeking affordable, practical solutions for food storage in a growing consumer economy. With refrigerators becoming more common, people needed better ways to preserve leftovers and reduce waste. Tupperware met this demand with its functional, attractively designed containers, which were soon produced in vibrant colors inspired by natural elements. The brand eventually opened a storefront on Fifth Avenue, transforming what was once a utilitarian item into a household staple.

In 1947, Brownie Wise, a divorced single mother in Detroit, discovered Tupperware and quickly recognized its potential after mastering the unique sealing mechanism. Drawing on her previous experiences in marketing and home-based product demonstrations, Wise introduced a party-based sales strategy. She launched gatherings called “Polly-T” parties (later known as Tupperware Parties), where hosts and trained saleswomen would demonstrate Tupperware products in a fun, hands-on environment. Her famous demonstration involved filling a Wonder Bowl with liquid, “burping” the lid (sealing it tightly), and tossing it to show off the spill-proof seal.

Figure 1: Brownie Wise Tosses Liquid-Filled Tupperware Container to Woman in 1950s Tupperware Party [3]

These events resonated with postwar women seeking both social interaction and extra income without disrupting their domestic responsibilities. Wise’s exceptional direct-sales marketing strategy caught the attention of Tupper, who appointed her as head of marketing vice president of Tupperware, positions that were rarely held by women at the time. Tupperware’s direct-selling strategy was executed through Tupperware parties and other in-person gatherings, where independent sellers demonstrated products and sold them directly to consumers. Tupperware subsequently exited retail channels in 1951 and shifted entirely to its direct-selling model, which remained the company’s sole marketing strategy until very recently [1]. To clarify, Tupperware did not pursue digital marketing at all for the majority of the company’s lifetime, only appearing for the first time in physical locations with its debut on Target shelves in 2022 [6].

Wise built a strong female salesforce and further boosted morale and performance through “Jubilees,” celebratory events that fostered community and rewarded top sellers. Wise believed that “if we build the people, they’ll build the business;” her strategy transformed Tupperware into a thriving direct sales empire and made her the first woman featured on the cover of BusinessWeek [1].

In 1958, Tupper sold the company to Rexall Drugs for $9mm and moved to Costa Rica. Rexall expanded the company, notably entering international markets in Europe and South America, before selling the company to Kraft in 1980. Using the same playbook of multilevel marketing and international expansion, Kraft continued to grow the company. Unsatisfied with Tupperware’s performance, however, Kraft spun it out via IPO in 1996. Through the 1980s, Tupperware’s patents had expired, allowing competitors to create competing products that cut into sales. Additionally, with women entering the workforce in record numbers throughout the second half of the 20th century, Tupperware’s multilevel marketing strategy focused on stay-at-home mothers had begun to lose relevance. These headwinds proved to be early indicators of greater issues Tupperware has faced over the past few years [2].

Business Model

Tupperware’s direct-selling business model operated under a sales force consisting of independent consultants. These consultants, primarily women, did not work as traditional employees but operated as independent contractors. Their role was to sell Tupperware products directly to consumers, often through Tupperware parties where they demonstrated products and took orders. Consultants earned commissions on their own sales and could earn additional income by recruiting others, creating a tiered structure that resembled what we know today as multilevel marketing. This model allowed Tupperware to scale its global reach without maintaining a large retail footprint, with the company expanding to 3.1mm consultants and eighty countries by 2015. Tupperware later expanded into adjacent sectors through acquisitions, including a beauty and personal care brand in Mexico [1].

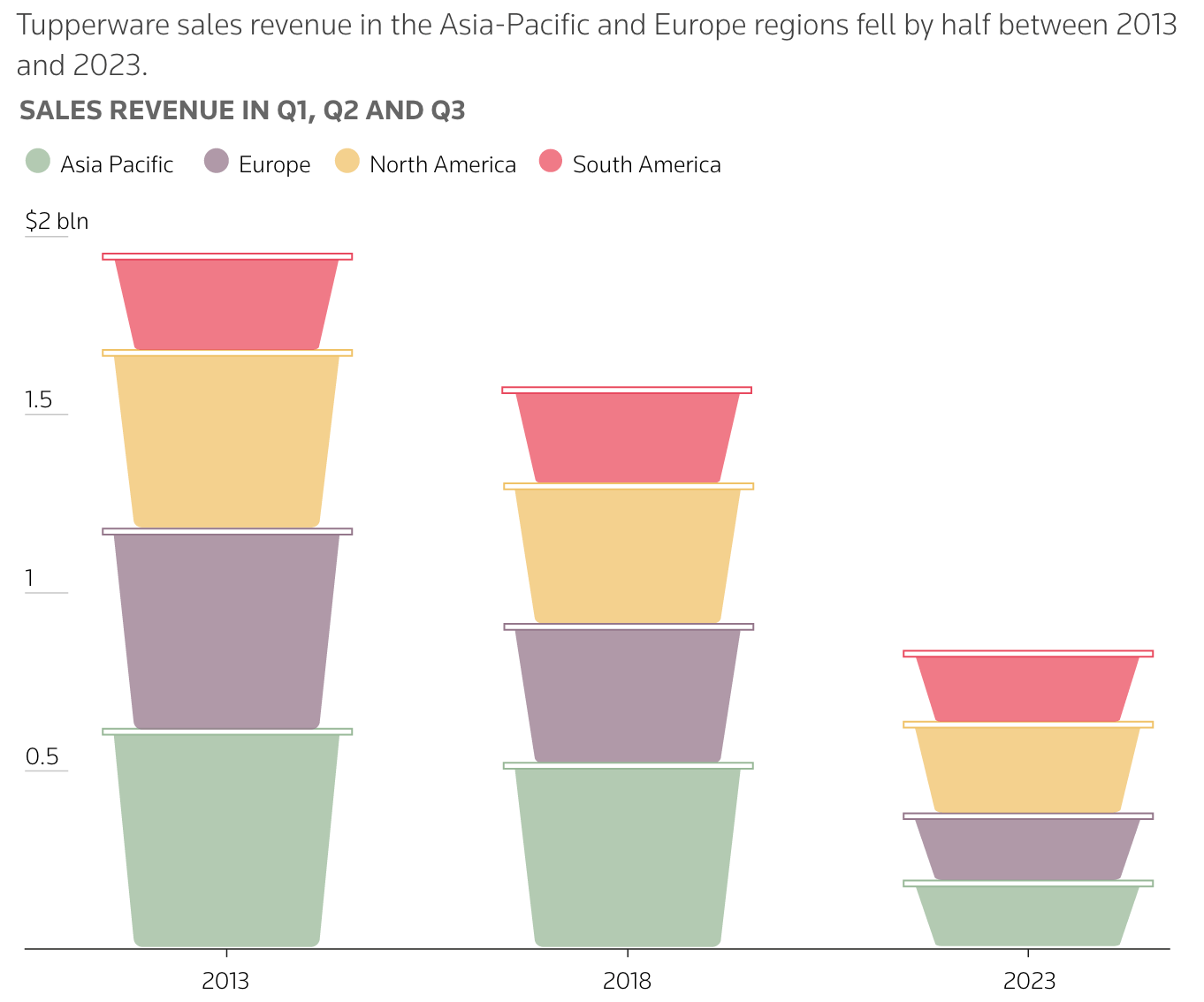

The company conducted business in four main regions: Europe, Asia Pacific, North America, and South America.

Figure 2: Tupperware Sales by Segment [10]

While we will focus on pre-distress financials in this section, the graph above gives a comprehensive view of the company’s performance over time, which will be relevant later. Most of the company’s revenue comes from foreign sales, with North America sales only accounting for around 25% of revenue in the past decade prior to the company’s financial struggles. Revenue peaked in 2013 at $2.7bn after steady growth from 2009. From 2013 to 2017, the company’s growth stagnated with an average revenue of $2.4bn, $1.6bn gross profit, $330mm operating income, and $220mm net income. We did not factor in net income for 2017 for our five year average as there was a particularly large net loss of negative $265mm in 2017 due to a $375mm non-cash income tax charge resulting from the enactment of the US Tax Cuts and jobs Act of 2017 (educed Tupperware’s U.S. corporate tax rate and triggered a one-time tax on previously untaxed foreign earnings) [7]. Tupperware’s market cap peaked at around $5bn in 2013, and decreased to around $3bn by the end of 2017 [8].

We also want to note that, while Tupperware’s performance began to steadily decline starting in 2018, the company’s financial performance overall had been relatively stable since 2009 [8]. This is important to recognize as Tupperware relied almost exclusively on its direct-selling model in this period. Despite the broader shift toward digital channels, Tupperware’s relative financial stability indicates that the company’s core business performance, and thus its legacy direct-selling strategy, remained relatively effective for nearly a decade. Even as the pandemic forced many stores to rely exclusively on direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales, Tupperware stayed committed to its direct-selling strategies by taking Tupperware parties online, with e-commerce sales only making up around 4% of total revenue in 2020 [5].

2020 Refinancing Senior Secured Notes

As shown in Figure 2 and discussed in our review of Tupperware’s early-to-mid 2010s performance, the company’s previously stable financial trajectory began to erode after 2018. While the overall reusable storage container market grew from $1.35bn in 2014 to $1.44bn in 2019 [11], revenues for Tupperware decreased for three years in a row from $2.3bn in 2017 to $1.6bn in 2019 [9]. The decline in revenue was largely driven by a drop in Tupperware parties, as consumers increasingly had less time or interest in attending in-person gatherings, and competitors like Rubbermaid and Glad adopting omnichannel sales channels. Despite the prevalent shift toward digital sales, Tupperware held steadfast in their direct-selling strategy even as other direct sellers began adopting digital strategies. Pampered Chef (another direct-seller of kitchen supplies), for example, reported digital sales accounting for over half of revenues in 2019, up from 10% in 2014, after successfully integrating digital channels into its business model. Additionally, the company faced leadership instability, with no permanent CEO following the departure of Rick Goings after more than two decades as CEO and the brief 18-month tenure of his successor, Patricia Stitzel [11].

While Tupperware’s sales strategy was beginning to show signs of faltering, the company’s bonds still traded around par as creditors believed the company could meet its financial obligations given its leverage profile: a $272mm Five-Year Revolving Credit Agreement and a $600mm 4.75% Fixed Rate Senior Secured Notes due 2021 [9].

The COVID pandemic in 2020 only accelerated early signs of failure in Tupperware’s business model. The shutdown of social interaction due to the pandemic severely impacted Tupperware’s direct sales strategy. Q1 2020 revenue fell an additional 23% on a quarterly year-over-year basis, with the number of direct sellers falling to around 490,000 globally, reflecting a 15% year-over-year decline. Given this impact to the business, combined with the disclosure of an investigation into financial reporting errors by Tupperware’s Mexican beauty business, Moody’s cut Tupperware’s bonds to single-B in February 2020. Tupperware’s single-B rating placed it in the speculative / junk rating, below investment grade. By May 2020, the bonds had traded down to a low of thirty cents on the dollar due to concerns about Tupperware’s ability to repay the soon-maturing notes in 2021. At this point, market cap was also fell to $130mm [8]. With no insight into the future of the pandemic and a cash burn of nearly $50mm in Q1 2020, the situation looked dire for Tupperware [12].

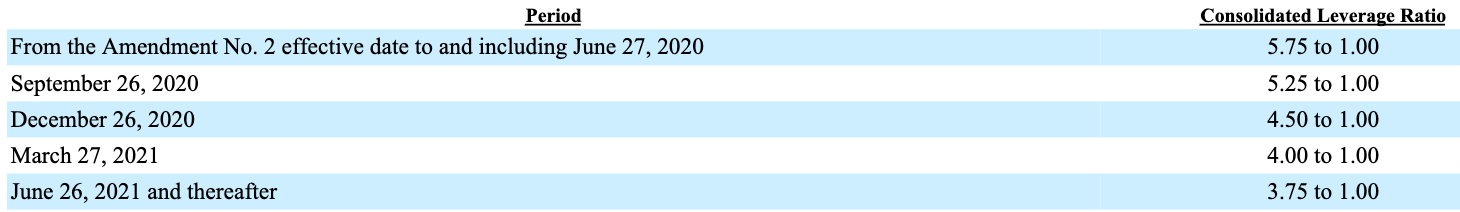

First, in February 2020, creditors agreed to amend the credit docs governing the Revolving Credit Agreement to increase the leverage ratio threshold from 3.75x to 5.75x. In Q4 2019, the company had total debt of $875mm and adjusted EBITDA of $240mm, giving a leverage ratio of 3.6 [25]. The increase in leverage ratio threshold was done as a preventative measure to ensure Tupperware did not default, as its leverage ratio at the end of 2019 was nearing the limits provided by the debt docs [9]. Over the next near, the leverage ratio would gradually return back to the original 3.75x:

Figure 3: Leverage Ratio Adjustment Timeline [9]

Second…

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Get Access to the Restructuring Drive

- See Sources and Backups to All Free Writeups

- Join Hundreds of Readers