Welcome to the 167th Pari Passu Newsletter.

Last week, we published an extremely detailed piece covering the 2025 Distressed Investing Conference. One of the key themes in the Liability Management Exercise (LME) panel was how litigation shapes deal structure: panelists cited Serta’s Fifth Circuit reversal as an example of how companies are moving away from relying on open market purchase (OMP) provisions to execute uptiers. As we pass the one-year anniversary of the Serta decision, it is worth recalling that another decision issued on the same day upheld a different uptier. While much of the legal spotlight around uptiers and creditor-on-creditor violence has focused on the landmark Serta transaction, the case of Mitel offers a fascinating contrast worth exploring.

In today’s writeup, we will explore Mitel’s changing position within the unified communications industry, the company’s 2022 uptier and 2025 Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and compare the court’s reasoning to other recent LME rulings to understand what’s changing in the evolving LME playbook.

Introducing Our New Sponsor: AlphaSense

Before we get started, I’m pleased to welcome AlphaSense as a sponsor of the Pari Passu Newsletter. As an analyst who used this tool in my previous full-time investing role, this is very exciting, so let me tell you more!

AlphaSense is a leading market intelligence and research platform. It is designed for investors and advisors operating in complex, time-sensitive environments where speed, depth, and differentiated insight are critical.

Since I started using the tool in my role (and now, for the newsletter), it has become an essential part of how I analyze companies, industries, and evaluate investment opportunities. Particularly when timelines are compressed, and public disclosures alone are insufficient (which is almost always the case in credit and special situations). Based on that firsthand experience, it is a tool I confidently recommend to readers of this newsletter.

At a glance, AlphaSense delivers:

Unmatched expert insight: Access to 240,000+ expert call transcripts across 24,000+ public and private companies, with approximately 6,000 new transcripts added each month, particularly valuable to get conviction in a differentiated thesis

Early signals beyond public disclosures: Channel Checks and expert synthesis surface demand trends, operational realities, and competitive shifts before they appear in filings or earnings calls

Research at true scale: Search and analyze 500mm+ documents, including filings, broker research, earnings calls, news, and industry publications, all in one platform. Really helpful to save time and ensure you are not missing anything.

I strongly encourage readers to explore AlphaSense firsthand. AlphaSense is offering Pari Passu readers a complimentary free trial, providing access to the platform’s research, expert insights, and finance-focused AI capabilities (I could spend 1,000 more words on this, but we need to get to today’s writeup).

You can request a free trial of AlphaSense for yourself here.

I’m excited to partner with AlphaSense and look forward to bringing their insight and capabilities to the Pari Passu community.

To kick things off, they have made available to anyone a great report on AI covering:

The defining themes of 2025 (from the transformation of search and the rise of memory-enabled AI to the foundations laid for agentic systems)

What to expect in 2026 as AI becomes more proactive, specialized, and seamlessly embedded into products and workflows

Why 2026 will be the year of measurable ROI.

Thank you, AlphaSense!

Unified Communications Industry Overview

The Unified Communications (“UC”) industry began to develop as businesses increasingly demanded more integrated ways to manage phone, video, and messaging tools. During the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, businesses primarily relied on switchboards to route phone calls. These switchboards were located in telephone company offices and were operated manually by human operators, who physically connected calls by plugging wires into jacks on a large panel.

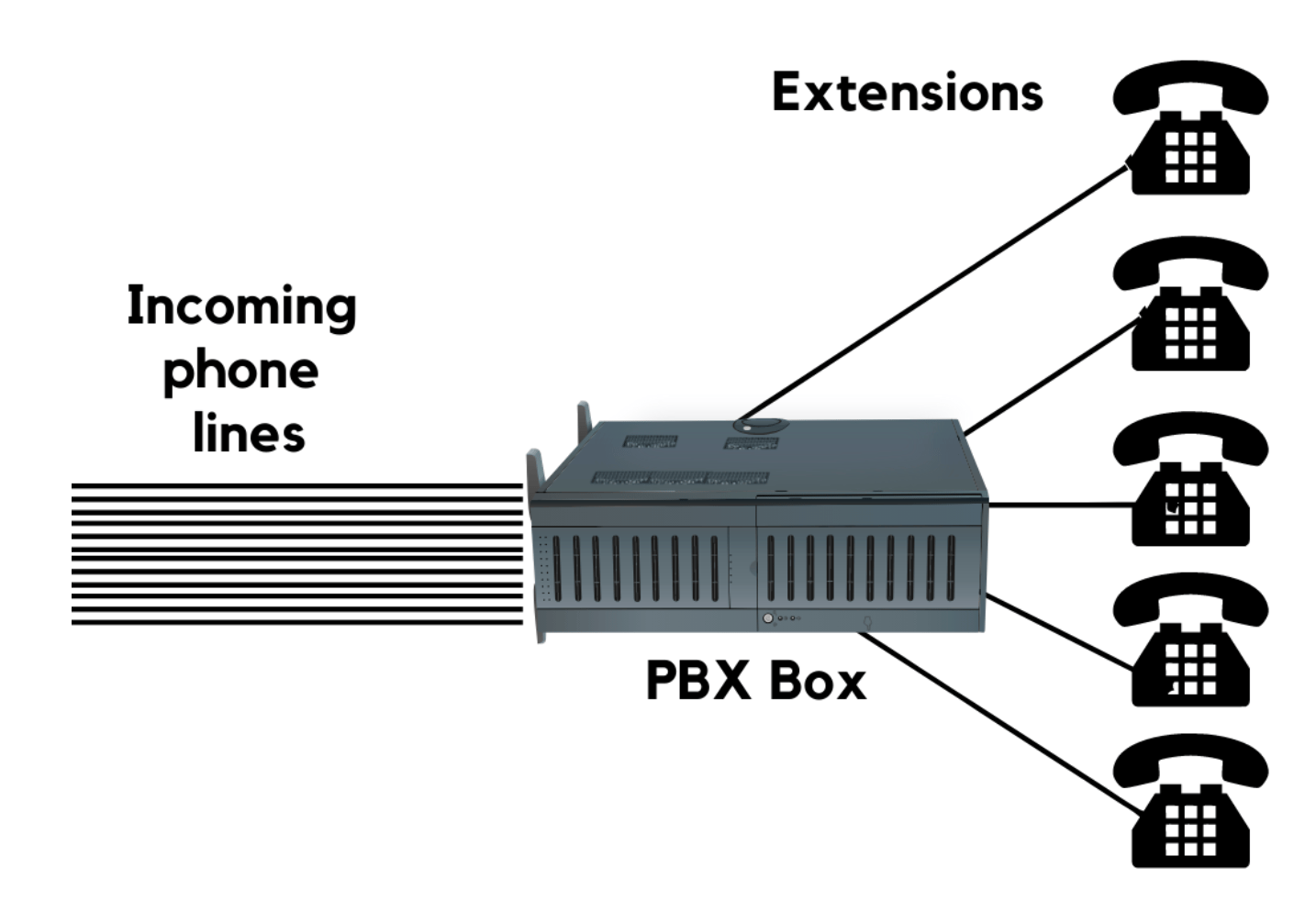

In the mid-twentieth century, the private branch exchange (PBX) system was introduced, which allowed businesses to handle their own internal call routing without relying on a separate telephone company for every phone call. The PBX system sat on-premise (on-prem), meaning there was a physical piece of hardware owned and maintained by a company. A PBX still relied on a public phone network for external calls via a few external phone lines from a telephone company, but connected internal calls so that they stayed within the office’s own system [2].

To better understand how PBX works, let’s take a look at the graphic below:

Figure 1: Traditional On-Prem PBX System [11]

Imagine you have a fifty-person office, and everyone has a desk phone. Without a PBX, you would need fifty separate phone lines from the phone company, which would equate to fifty monthly phone bills. After installing a PBX box inside the office, fewer phone lines are needed to connect to external parties. Let’s say, for simplicity, that only ten phone lines are now needed from the phone company. Within the office, the PBX connects all fifty desk phones together, and employees can call each other directly using the PBX. For outside calls, the PBX shares the ten external lines. If one is available, the call gets routed out. To clarify, while the company can now streamline all internal calls, it still needs a phone line for every external call the office wants to make; the office can only make or receive as many external calls at once as the number of phone lines it has. In doing so, the PBX made business communication more time and cost-efficient.

After the invention of on-prem PBX systems, voice over internet protocol (VoIP) emerged in the early 2000s to enable companies to take advantage of the internet to transmit phone calls as data packets. VoIP eliminated the need for physical telephone lines altogether, instead allowing voice communication to travel over existing internet networks. This shift laid the groundwork for cloud-based communication services and ultimately gave rise to Unified Communications as a Service (UCaaS), where companies could access voice, video, and messaging tools entirely online without owning or maintaining physical hardware. This new model, known as a multi-tenant (multi-customer), subscription-based UCaaS model, allows many businesses to share the same cloud infrastructure while paying a monthly fee per user, similar to how companies subscribe to services like Microsoft 365. The cloud refers to remote servers hosted in data centers that deliver computing resources over the internet, and it allowed the UC industry to scale rapidly; by offloading infrastructure to the cloud, UC providers could serve many customers at once and update software centrally [2].

In the UC market today, companies typically pursue one of two business models [3]:

Pure-Hosted Cloud Players: Cloud providers run call control (technology that manages phone calls in a network), as well as handle media like voice and video, and offer collaboration tools, all through a shared online platform. This setup is called “multi-tenant,” meaning many different businesses use the same system at once. Everything is accessed through the internet, so companies don’t need to install or maintain any equipment on-site. Clients typically subscribe on a per-seat per-month basis, and key market players include Microsoft Teams, Zoom, and RingCentral.

Hybrid Players: Hybrid providers sell both on-prem PBX hardware and cloud solutions for smaller or branch offices. On-prem services and products are often provided for larger enterprises because they can spread fixed infrastructure costs across a larger base, while smaller businesses typically opt for cloud solutions to avoid large capital investments. On-prem products are typically sold as an initial sale of hardware and software, with ongoing recurring maintenance revenue. Prominent vendors include Mitel, ShoreTel (pre-acquisition, which we will discuss later), and Cisco.

Mitel Company Overview

Founded in 1973 in Canada, Mitel is a leading global provider of UC solutions that provides telephony, messaging, and video call services for businesses. At its peak, Mitel offered hardware, software subscriptions, and professional support services for over 75mm users in nearly 150 countries [1].

Mitel’s Hybrid Business Model

In 2024, Microsoft led the global unified communications market with a 45% market share and $32bn revenue, followed by Zoom and Cisco (each with around 5% of market share and $4bn annual revenue). The remaining 45% is highly fragmented across a mix of cloud-only, hybrid, and on-prem players; some players include RingCentral, 8x8, Avaya, Google Meet, Slack, Mitel, and Fuze. Mitel does not directly compete with Teams or Zoom for raw scale. Instead, Mitel’s strength lies in serving mid-to-large enterprises that want to keep some of their hardware equipment (like servers or phone desk networks) while also using cloud-based tools. This hybrid approach gives customers more control over their setup as opposed to fully cloud-based providers like Zoom [5].

The 65mm businesses Mitel currently caters to operate in a variety of verticals such as hospitality, education, and healthcare. The company generates revenue from three main segments, which make up around 90% of annual revenue [1]:

1. Software & Subscription Products: Software & Subscription Products include the software and cloud-based tools businesses use to manage communications, including phone calls, video meetings, and contact centers. Customers pay for services like virtual phone systems (which replace desk phones) and all-inclusive collaboration platforms similar to ones offered by Microsoft Teams. These tools can be installed on-site, accessed remotely via the cloud, or a combination of both in a hybrid model. Software and subscription products made up around 40% of FY 2024 revenue.

2. Professional & Support Services: Professional & Support Services include services that help customers install, customize, use, and maintain Mitel’s products. An example of this kind of service is integration support, where Mitel’s teams and partners make sure Mitel’s tools work well with a customer’s existing business systems. This segment made up around 30% of FY 2024 revenue.

3. Hardware Products: Hardware Products include sales of IP desk phones, conferencing hardware, attendant consoles, and wireless solutions, making up around 20% of FY 2024 revenue. For hardware production, Mitel partners with two high-volume contract manufacturers, Flex Ltd. and Celestica, Inc., and other smaller vendors for legacy equipment.

Mitel sells its products and services using two methods: directly to consumers and indirectly through a global network of over 6,000 partners. These global partners include distributors and channel resellers, and nearly 90% of the company’s global sales come through these indirect channels [1].

Mitel’s cloud UCaaS platform (branded MiCloud) is primarily built and maintained by its in-house engineering team. Though Mitel licenses some third-party software components, the bulk of the cloud’s proprietary code is developed internally and capitalized as software development costs. Before Mitel went private in 2018, the company was generating $1.1bn in revenue with a 45% cost of revenue in 2017. Cost of revenues comprised device manufacturing costs, channel partner incentives, third-party software licensing fees, and the amortization of capitalized development expenditures [4].

Corporate History

Now that we have a better understanding of Mitel’s business model and the UC industry, let’s explore the company’s history to understand the events that preceded its current distressed situation. Mitel was founded in 1973 and has pioneered many breakthrough technologies in the UCaaS space, including the invention of a virtual PBX that allowed people within a company to make internal or external calls, and for incoming calls to be directed to the correct party without going through telephone wires [1]. The company mainly relied on inorganic growth through acquisitions to support its business, taking on more than a dozen acquisitions between 2011 and 2018 alone [12]; in this section, we will focus on a few major acquisitions. The company’s growth journey launched in 2007, when Mitel acquired Inter-Tel, a U.S. provider of business phone systems and other UC solutions [4].

Next, in April 2010, the company underwent an IPO that aimed to raise $200mm in order to, among other purposes, pay down some of the company’s existing debt incurred from the acquisition. Mitel priced its 10.5mm common shares at $14 per share, falling below the expected range of $18-20, for a total valuation of around $950mm [6].

From 2010 to 2013, Mitel’s revenue plateaued at around $600mm with adjusted EBITDA hovering around $85mm, yielding around 15% EBITDA margin [4]. The company attributed its lack of revenue growth to the macro challenges following the Great Financial Crisis, but RingCentral (one of Mitel’s largest competitors) had more than tripled its revenue from FY 2010 to $150mm in FY 2013, and 8x8 (another major competitor) had nearly doubled its revenue to over $100mm in FY 2013 [7] [8]. Evidently, the main issue was not the macro-environment. Mitel simply failed to pivot quickly to cloud-native UCaaS; the company’s revenue was not growing as fast as its peers, and as Mitel failed to meet evolving customer needs, the company continued to lose market share as a result.

In 2014, Mitel purchased Aastra Technologies for $370mm [9]. Aastra itself was a hardware-centric PBX company, and rather than accelerate Mitel’s shift to a multi-tenant, subscription-based UCaaS model that had proven effective for competitors, the acquisition deepened Mitel’s reliance on hardware. The acquisition did, however, expand Mitel’s geographic footprint into Latin America while strengthening its position in Europe and Asia; following the acquisition, FY 2014 revenue and EBITDA nearly doubled to $1.1bn and $170mm from FY 2013, but EBITDA margin stayed the same around 15%. Importantly, Mitel was still posting losses due to high SG&A and R&D costs that, together, consumed around 80% of annual revenue. The company also recorded $60mm in free cash flow, and now had $650mm in debt against only $90mm in cash [4]. Mitel’s gross margin remained flat around 50% from 2010 to 2014 [4], while competitors like RingCentral had grown theirs from under 58% in 2011 to 65% due to their shift from hardware to subscription-based models [7].

Between 2015 and 2016, Mitel’s top line remained essentially flat at just over $1bn and around $140mm EBITDA as the business continued integrating Aastra [4]. Meanwhile, the pure-cloud UCaaS market was beginning to shift dramatically, with cloud-native platforms like Microsoft Teams and Zoom rapidly gaining market share through seamless integration with existing software ecosystems like Microsoft 365, Google Workspace, and popular CRM and project management tools. It wasn’t until 2017, after Mitel’s $530mm all-cash acquisition of ShoreTel, that the company began to transition to pure-cloud UCaaS offerings. With the acquisition, Mitel aimed to use ShoreTel’s existing technology to help its existing customer base of over 60mm businesses move to the cloud more easily, offering them a smoother transition from traditional on-prem phone systems to a subscription-based service without needing to replace their entire existing systems [10].

Let’s quickly summarize Mitel’s financial performance before the company went private in 2018. From 2014 – 2017, the period during which Mitel acquired and was integrating Aastra and ShoreTel, revenues stayed flat at around $1bn, with SG&A consistently making up 30% of sales and R&D consuming another 10%. With high opex primarily resulting from integrating its newly acquired companies, Mitel had been posting break-even operating margins but decent free cash flow ranging from ~$20mm to ~$80mm [4]. By 2018, Mitel’s customer base consisted of 70mm businesses and users across over 100 countries [11].

In April 2018, Searchlight Capital Partners (a private investment firm focused on PE and credit investments in North America and Europe) acquired Mitel in a $2bn all-cash transaction at a 9.5x EBITDA multiple. Right before the company was taken private, Mitel had a market cap of around $1.6bn [21]. As part of the transaction, Mitel took on a few significant pieces of debt: $1.1bn term loan, $260mm junior term loan, and a $100mm revolver. In the company’s final public filing in Q3 2018, Mitel was generating around $1.3bn in revenue with 60% gross margin and barely breaking even. After the acquisition, Mitel carried around $1.4bn in total debt, with a net leverage ratio of 6.2x and an LTV of around 70% [4]. Below is the company’s capital structure after the November 2018 acquisition closing date (interest rates and exact maturity dates were not publicly available):

Figure 2: Mitel’s Pro Forma Capital Structure as of November 2018 [4] [15]

CEO Turnaround and 2021 RingCentral Partnership

Over the next few years, Mitel focused on integrating its series of acquisitions. Shortly after being acquired by Searchlight in 2018, the company underwent management changes when CEO Richard McBee stepped down and was succeeded by Mary McDowell. McDowell was the former CEO of Polycom (a developer and manufacturer of workplace collaboration systems, like video conferencing services) and had overseen the successful financial turnaround of Plantronics before it was acquired by electronics company Plantronics in 2018. One of McDowell’s primary goals at Mitel was to improve the company’s operational performance, similar to the transformation she led at Polycom, through continuing the company’s goals of migrating its existing on-prem users to the cloud [12].

Interestingly, there was significant overlap between McDowell’s past roles and Mitel’s corporate history. In 2016, Mitel had publicly announced its plans to acquire Polycom, but the deal fell through when Siris Capital (a tech-focused PE firm where McDowell was a senior advisor) made a more compelling offer. McDowell was appointed CEO after the acquisition of Polycom by Siris [12].

Meanwhile, the UCaaS industry experienced a wave of competitor consolidation. Around the same time that McDowell became Mitel’s new CEO, Mitel was exploring a merger with Avaya, a competitor historically focused on on-prem phone systems that was transitioning into a cloud communications provider. However, in October 2019 (after Avaya had emerged from Chapter 11 in December 2017), Avaya opted instead to pursue a strategic partnership with RingCentral. As we have mentioned throughout this writeup, RingCentral was one of the industry leaders in cloud-based UC solutions. The $500mm partnership aimed to modernize Avaya’s outdated on-prem systems by launching “Avaya Cloud Office by RingCentral,” a cloud-based service that ran on RingCentral’s cloud technology but was branded and sold by Avaya; Avaya brought a large global customer base and strong sales and distribution network to the partnership. This partnership was widely seen as a lifeline for Avaya, which lacked a competitive in-house cloud solution and needed to quickly pivot amid its fragile financial health and lack of market share [13].

Following Avaya’s successful RingCentral deal and Mitel’s failed merger attempt with the company, Mitel pivoted toward its own strategic partnership with RingCentral in November 2021. Under the agreement, RingCentral became the only provider of cloud-based communication services for Mitel. The plan was to move all of Mitel’s existing customer base, regardless of whether they were using Mitel’s older, on-prem systems or its own cloud offerings, over to RingCentral’s newer cloud platform called the Message Video Phone (MVP) platform. By offloading the cloud migration of its customer base to RingCentral, Mitel was able to focus on its core UC offerings and enterprise partnerships. To support this transition, RingCentral paid $650mm to acquire key Mitel IP assets, including the company’s MiCloud Connect UCaaS platform, access to its customer base, and CloudLink, a proprietary technology that helped bridge on-prem systems with cloud functionality [1]. Essentially, this partnership functioned as a partial sale of most of Mitel’s UCaaS services. RingCentral acquired key assets and took over delivering all cloud-based communications services to Mitel customers going forward. This partnership was also different from Avaya and RingCentral’s deal. In Avaya’s case, the company offered a RingCentral-driven cloud communications service that was still sold as an Avaya product. In Mitel’s case, the company’s customers were fully migrated to a RingCentral-owned platform, with RingCentral operating the service directly.

However, the customer migration to RingCentral’s cloud platform was slower than anticipated in early 2022. While Mitel had eventually made the switch to integrate cloud into its existing infrastructure, the company made the transition too late, while competitors had already established strong cloud-native platforms and captured significant market share. Additionally, the COVID pandemic also had a negative impact on the company. Though the pandemic accelerated the shift to remote work, which in theory should have been a profitable opportunity for a UCaaS company like Mitel, the company was unable to adapt to accelerating hybrid communications needs due to liquidity constraints. Macroeconomic challenges also led to global chip shortages and rising input costs for hardware products, further limiting Mitel’s ability to capture the increase in demand for UCaaS services [1].

No public information about the company is available after its 2018 acquisition by Searchlight. However, we know that during this period, Mitel’s total debt amounted to $1.2bn by the end of 2022. While this debt load was lower than the $1.4bn of debt the company held at the time of its 2018 acquisition by Searchlight, Mitel was far less equipped to manage it in 2022. The combination of low revenue from slow customer migration, increased costs due to the pandemic, and other macroeconomic headwinds left Mitel with less cash flow and flexibility to service its debt load. These events pushed Mitel to explore out-of-court restructuring solutions, and the company ended up pursuing a non-pro rata uptier with a majority of its term loan lenders in the fall of 2022 [1].

2020 Serta Uptier Precedent

Before we dive into Mitel’s LME, let’s do a quick review of what an uptier is and how to execute one. Uptier transactions allow a majority of secured lenders to subordinate minority lenders by amending credit docs to create a superpriority tranche, then exchanging their old debt for new senior debt. This exchange is often supported by new money financing. Uptiers hinge on two clauses found in credit docs: (1) whether lien subordination provisions can be amended by a simple majority and (2) whether non-pro rata debt-for-debt exchanges are permitted, often via the open market purchase (OMP) loophole. Because many credit docs require the unanimous consent of lenders to raise new debt (which could have a higher priority than existing debt), the first requirement ensures a simple majority of lenders can amend this provision. The OMP provision in the second requirement is the key concept underpinning the entire structure and legality of an uptier. As a review, an open market purchase is a contractual carve-out that allows a borrower to repurchase its own debt on a non-pro rata basis (typically at a discount) without offering the same terms to all lenders [14].

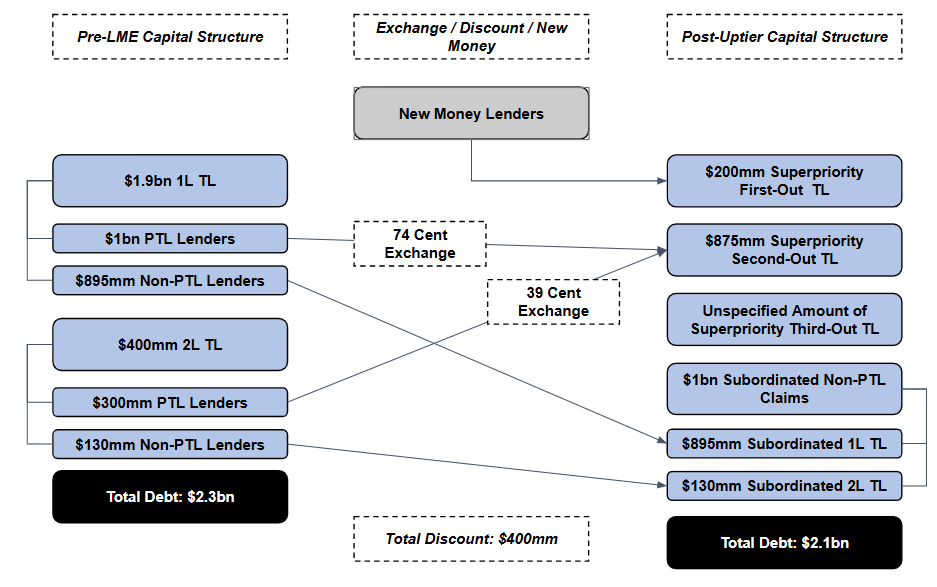

Prior to the age of aggressive LMEs, OMPs were used by lenders to repurchase debt at a discount as a deleveraging measure. It wasn’t until Serta’s uptier that this provision was weaponized to facilitate coercive out-of-court restructuring solutions through non-pro rata sharing provisions. To first summarize the transaction itself, Eaton and Invesco led the participating lenders to create three new debt tranches, two of which were used, and the third was reserved for potential future use with no outstanding debt at the time of the uptier. The participating lenders contributed $200mm in new money, creating the new superpriority first-out tranche. Then, they exchanged their existing 1L debt at a 26% discount and 2L debt at a 61% discount into the new superpriority second-out tranche [14].

Figure 3: Serta’s Capital Structure Before and After 2020 Uptier [14]

This transaction left the minority group, including Apollo and Angelo Gordon (who had initially formed a group to propose a dropdown transaction), heavily subordinated. When the company filed for bankruptcy in January 2023, the minority group only got 1% of reorg equity, while the new first out claims received a $315mm post-reorg term loan, and new second out claims got almost all of the reorg equity. In response, minority lenders sued Serta. However, Judge Jones of the Southern District of Texas Bankruptcy Court sided with the participating lenders after citing adequate definitions of “open market purchase” in Serta’s credit docs.

Mitel’s 2022 Liability Management Transaction

Serta’s uptier was the first high-profile case to use the OMP loophole to execute a non-pro rata uptier exchange. Serta’s transaction, along with J.Crew’s famous IP dropdown, laid the groundwork for a wave of aggressive LMEs. Mitel followed this trend and executed its own uptier led by a majority of its first and second-lien term loan lenders in October 2022. In this section, we will outline the financial structure of the company’s transaction. Later, we will revisit this critical LME in the context of Mitel’s Chapter 11 filing, including an analysis of the company’s credit docs that enabled the transaction to be executed, as well as a comparative analysis of the legal mechanics behind the Mitel and Serta uptiers.

Along with its participating first and second lien lenders (“PTL Lenders”), Mitel executed an uptier in October 2022. A summary of the transaction can be seen below [17]:

Figure 4: Mitel’s Post-Uptier Capital Structure [15]

1L and 2L PTL lenders contributed $156mm in new money in the form of a new superpriority first-out tranche

1L PTL lenders exchanged $603mm of existing first lien loans into new superpriority second-out loans at a 5% discount to par

2L PTL lenders exchanged $152mm of second lien loans into new superpriority third-out loans at an 18% discount. These three new tranches were secured by the same collateral backing the existing first and second-lien loans. The proceeds of the transaction were used to pay down the company’s $90mm revolver maturing in November 2023 and replace it with a new $65mm revolver with a November 2025 maturity date; the new revolver was pari passu with the new money superpriority first tranche

Just like Serta’s uptier, non-participating lenders ($389mm in total claims across the 1L and 2L Term Loans) were excluded from the exchange entirely.

In total, Mitel captured a discount of ~$50mm on the exchange and was able to raise $156mm of new debt, increasing near-term liquidity and providing temporary relief; the company’s uptier effectively functioned as a refinancing meant to extend Mitel’s runway [15].

Post-Uptier Distress

You are about to reach the midpoint of the report. This is where the story gets interesting.

Free readers miss out on the sections that explain:

• Post-Uptier Distress

• Uptier Litigation

• Reversal of Serta’s Uptier

• Mitel’s Contrasting Decision

• Chapter 11 Filing and Emergence

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive.

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Full Access to Over 300,000 Words of Evergreen Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Access to the Restructuring Drive