Welcome to the 169th Pari Passu newsletter.

In today’s edition, we’re looking at Selecta, a pan-European leader in food technology and vending solutions, which was previously backed by KKR. Selecta’s June 2025 recapitalization transaction serves as a pivotal moment in the European distressed market, serving as a landmark creditor-led distressed disposal transaction. It is one of the first transactions that borrows the non-pro-rata LME playbook from the US and executes it in Europe. The transaction achieves a capital structure reset via a share pledge enforcement approved by the Netherlands Commercial Court, creating a tiered debt exchange and handing control of the business to the Ad-Hoc Group (AHG).

For this piece, we supplemented public disclosures with a detailed breakdown of the legal mechanics and structures at play. The post attempts to deconstruct the aggressive approach undertaken by the AHG. We will start by outlining Selecta’s business model and COVID-19-related headwinds, followed by the failed 2020 restructuring effort. Then, we’ll explore the mechanics of the Dutch Article 3:251 share pledge enforcement before diving into the problematic choice facing the non-AHG lenders. Lastly, the post identifies the interesting details that make this transaction unique, and potential options the AHG can exploit to improve its position. This post walks through the pre-2020 period (distress build-up), 2020 pandemic-induced restructuring, the failed recovery period, and finally the 2025 landmark transaction. While the 2025 transaction is complete on paper, the post-LME documentation remains open to amendments due to AHG dominance and is subject to immense legal scrutiny, leaving the ultimate validity of the June 2025 outcome still up for judicial review.

In case you missed recent LME Editions: City Brewing, Oregon Tool, Better Health, Bausch, Quest

The definitive account of AMC’s survival

9fin is offering Pari Passu readers early access to its multi-part account of how the cinema chain used a series of complex LMEs to stay afloat

This is the definitive account of the most audacious liability management projects in modern capital markets. Across four chapters, our investigation reveals the backroom negotiations, legal maneuvers, and extreme resourcefulness that saved AMC from bankruptcy.

From the creative strategies of Doug Ormond, to the extreme resourcefulness of Adam Aron and Sean Goodman and the perfectly timed meme-stock chaos unleashed by Keith Gill, this story has it all.

This is the kind of depth and sophistication (and entertainment) that you can only find on 9fin. Nowhere else gives you this level of access to the individuals, institutions, and new developments that are reshaping the distressed debt markets.

We are offering qualified Pari Passu subscribers access to a 45 day free trial of 9fin — that’s 15 days longer than usual. Click here to access the offer and sample some of 9fin’s latest coverage.

Selecta

Selecta, founded in 1957, is a Switzerland-based coffee vending machine company. It is the largest in Europe, with three times the market share of its next biggest competitor. Selecta provides a broad range of traditional and food technology solutions, along with machine installation and maintenance services. The company currently serves more than ten million clients daily, and has 304,000 machines installed across Europe. The company generated revenue of €1,145mm (at an exchange rate of €1 = $1.16, this corresponds to ~$1,328mm) and adjusted EBITDA of €204mm, resulting in an 18% margin.

Figure 1: Core Selecta Vending Machines

To further break down its operating footprint, the company operates through multiple sales channels: 16% public, 14% semi-public, 49% private, and 21% trade. The private (workplace) segment is the traditional “office coffee” segment (OCS). Under its traditional model, Selecta retains ownership of the installed machine base and provides it to corporate clients at no upfront cost, earning revenue solely through 'pay-per-cup' volume. In contrast, the rental model charges clients a fixed monthly fee, guaranteeing income and shifting utilization risk away from Selecta. Post-2020, the company has aggressively pivoted towards the rental structure to insulate itself from the structural decline in office attendance. The private channel is the most high-margin business for Selecta, but it is also the most sensitive to white-collar office attendance. The public/semi-public segment refers to high-footfall locations like airports and universities. These contracts are often won through significant upfront CapEx and rent payments to landlords, but this is justified by the high sales volume generated. The trade business is where Selecta sells ingredients (like its own Pelican Rouge coffee beans) and machines directly to other businesses.

Most of the revenue is driven by coffee and water, amounting to 43% of revenue for 2024, followed by vending and food (31% of 2024 revenue). The remaining 26% of 2024 revenue was driven by the trade segment, which effectively functions as a B2B wholesaler, selling ingredients and hardware to third-party businesses rather than vending to consumers. It is important to note that while the trade segment sells coffee products, these B2B sales are reported separately from the consumer-facing coffee and water segment (43% of revenue). Selecta operates with a diversified client portfolio, with the top 10 clients only making 11% of FY24 revenue [1]. In terms of geographic breakdown, the company is split 33%, 33%, and 34% between North, South/UK&I, and Central Europe, respectively [1].

Business Headwinds

To fully understand the roots of Selecta’s distress, we must first contextualize its long history of private equity ownership. Selecta was owned by Allianz Capital Partners from 2007-2015, a period characterized by relatively stable but low-growth performance before KKR acquired the business to pursue an aggressive buy-and-build strategy. Allianz acquired Selecta at 8.6x adjusted EBITDA at an enterprise value of €1.1bn, contributing €240mm in the form of sponsor equity. KKR purchased Selecta from Allianz Capital Partners in October 2015. This acquisition was structured as a debt-heavy rescue where KKR, which was already a creditor through a €220 million PIK loan provided in 2014, paid a nominal equity price to take control of a business burdened by €866 million in existing debt, effectively valuing the company at approximately 7x of its then-Adjusted EBITDA of €127 million. KKR executed an aggressive buy-and-build strategy, and perhaps the two most important moves in the KKR era were the acquisitions of two key competitors: Pelican Rouge for €554mm in 2017 and Gruppo Argenta for €224mm in 2018 [3]. Pelican Rouge is a coffee services and vending company, while Gruppo Argenta was a leading vending and coffee service provider in Italy. While these two landmark acquisitions solidified Selecta’s position as a market leader in Europe, it also significantly burdened the balance sheet due to the use of heavy debt to finance these acquisitions. Essentially, the overarching thesis was based on synergies and stable recurring cash flows from daily coffee consumption across Europe.

However, as noted above, the business model is at its core heavily sensitive to footfall in the workplace and public areas. Thus, the business proved to be exceptionally fragile to the structural shifts caused by the onset of the pandemic. Essentially, there are two main drivers that derailed the business: revenue pressure and cost rigidity.

The structural decline in office attendance caused a severe revenue contraction in 2020–2021, breaking down the unit economics of the installed machine base. To better understand this dynamic, we can analyze the classic industry metric, which is sales per machine per day (SMD): even a 10-15% drop in SMD can have a meaningful impact on unit economics. We can look at SMD as a core efficiency metric that exposes Selecta’s operating fragility during this period. For Selecta, the blended SMD for FY2019 was €9.90; this average was likely reduced by the public channel [1]. Public machines rely on sporadic impulse buys, while the workplace segment drives higher averages through the recurring daily coffee/food consumption of office workers. During 2020, Selecta’s SMD dropped to around €7.20 (27% decrease) [1]. This implies that thousands of machines likely became unprofitable during the COVID era, failing to generate enough sales volume to cover the fixed cost of the logistical network. To understand the severity of this decline, we must recognize that Selecta’s model relies on density and volume to cover its high fixed costs. With SMD plummeting to €7.20, thousands of machines likely fell below their cash-flow breakeven point. This meant that for a significant portion of its fleet, Selecta was effectively paying more to service the machines than it was collecting in cash, instantly turning a profitable asset base into a source of liquidity drain.

Compounding this revenue pressure was the rigid nature of the cost base. Selecta’s operating leverage worked against it as route-based logistics could not be reduced in proportion to the drop in sales volume. The company operates a massive logistical network (which adds to its moat in good environments) with thousands of route drivers and technicians, and owns a fleet of service vehicles. Essentially, the cost to service a vending machine is largely fixed: a driver must visit a machine to clean, service, and restock regardless of whether the machine sold 100 or 150 cups of coffee in that given week.

The two operating dynamics listed above lead to crucial implications for the business during a distressed environment. First, the firm cannot linearly cut route frequency/coverage with declining revenue. For instance, if a driver starts visiting a machine less frequently, food quality is ruined, and this may lead to a worse customer experience, leading to increased churn. Second, the private channel never fully recovered after the pandemic, as work from home gained traction, leading to a fundamental shift in the end-market behavior of the largest sales channel for Selecta. Even with hybrid work (three days a week in the office), the SMD for that machine effectively falls by around 40%. Therefore, the core drivers for distress were all these factors combined: the top line continued to shrink due to pandemic-induced factors, while the fixed cost of “last mile” delivery cannibalized the shrinking revenue, leading to EBITDA margin compression to the point where it could no longer service Selecta’s debt load.

2020 UK-Led Cross-Border Restructuring

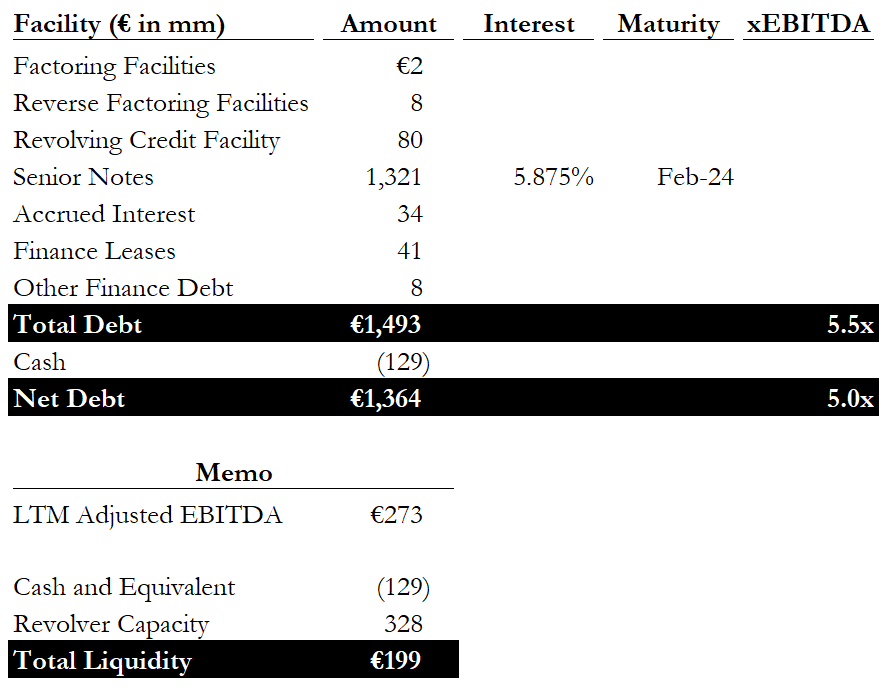

Figure 2: Cap Table as of 4Q 2019

The COVID-19 pandemic served as the immediate trigger for Selecta's first restructuring. Almost overnight, the company faced a liquidity crunch as lockdowns across Europe caused revenue to drop by approximately 50% in the early months of the pandemic. In 2020, management estimated €25mm to be the minimum required liquidity for the business, while it considered a €100mm liquidity headroom as adequate for uninterrupted operational performance [4]. With the business facing a €11mm and €20mm liquidity shortfall by October and December, respectively, management was forced to execute a dual-track response: a severe operational restructuring to stop the bleeding, and a financial restructuring to bridge the gap to a recovery they hoped would come in 2021.

Prior to executing the financial restructuring in 2020, Selecta initiated a comprehensive operational restructuring to stabilize the business [2]. First, many POS (point of sale) machines were taken out of the field in FY20 (roughly 11,000 machines or 3% of 400,000), and another 15% of POS machines in FY21. Furthermore, Selecta implemented reductions in disbursements through working capital management, deferred government payments, and strict CapEx controls. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, Selecta made substantial reductions in both the corporate and field labor force (roughly 40-80%, showing the severity of the crisis) in FY20 [4]. This radical downsizing was necessary to force the company's fixed cost base to match the sharp drop in activity.

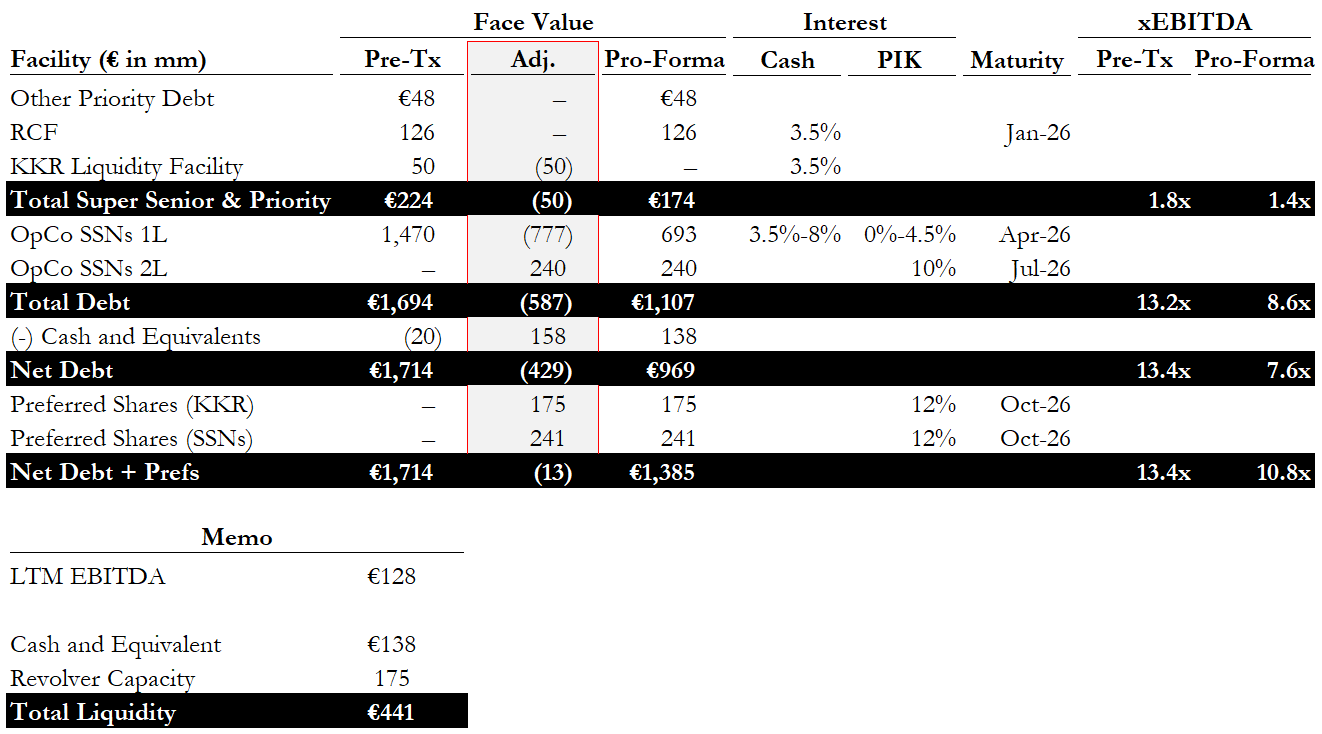

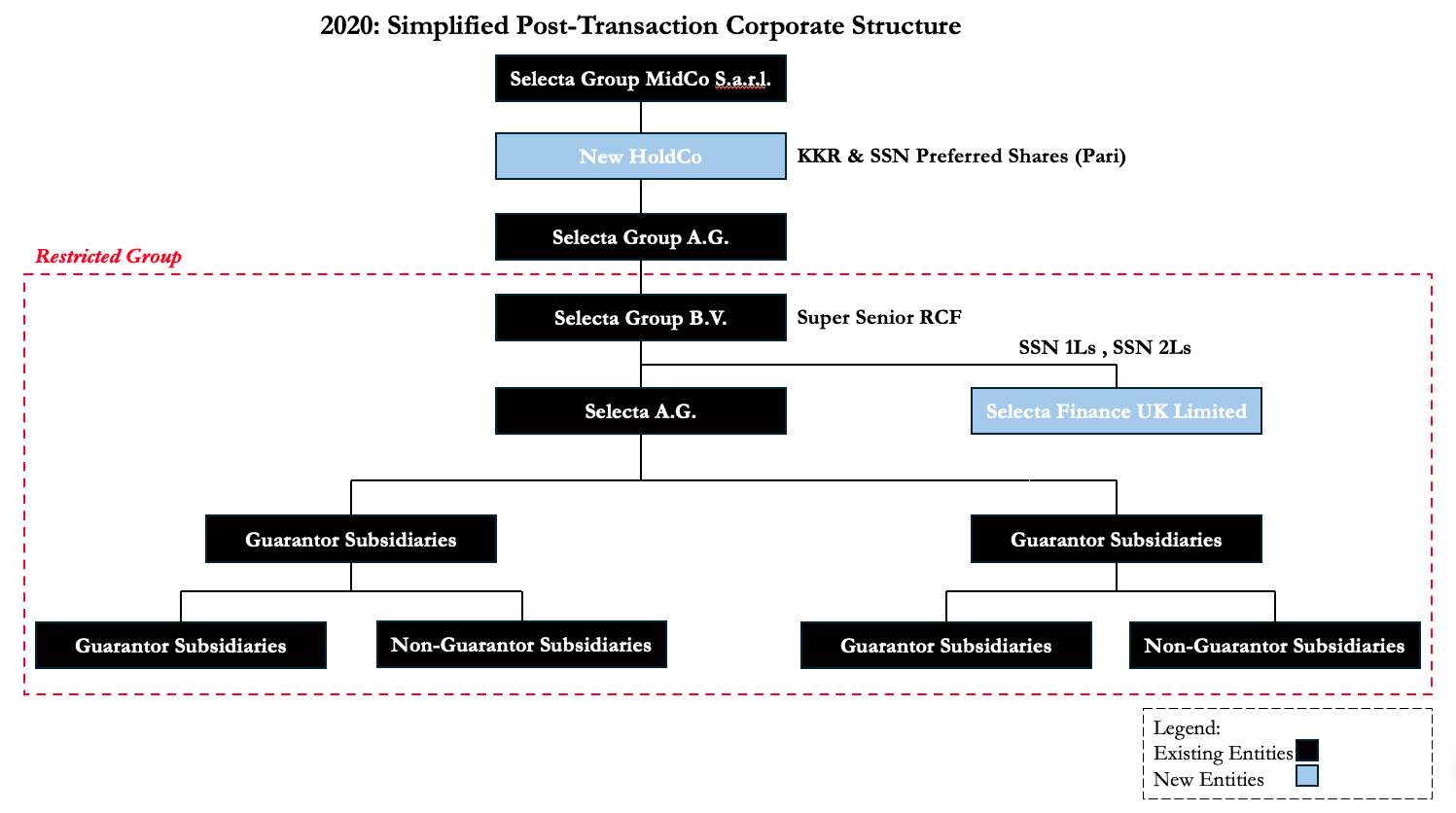

The focus of this post is on the June 2025 transaction, but it is important to walk through the basics of the 2020 transaction. The first step of the transaction was a €175mm new money injection from KKR (the sponsor) to provide liquidity support for the operational turnaround of the business. The entire €175mm investment from KKR was not entirely new capital injected into the business: €125mm was new money, while the remaining €50mm was a drop-down of the pre-existing emergency loan KKR had provided in March 2020 [4]. Instead of repaying this loan in cash, Selecta converted it into the new capital structure. Both components of the facility were invested at the HoldCo level in the form of preferred shares. Thus, the new KKR investment sat junior to the OpCo level debt, but senior to the old equity. KKR remained the majority owner of this business through this transaction. The second step of the transaction was exchanging the senior secured notes into new instruments maturing in 2026. Essentially, for every €100 of existing senior secured notes, €64 of the claim remained at the OpCo level, while €16 of the claim was moved up to the HoldCo level as preferred shares (pari with the KKR preferred shares). As a result, lenders realized a 20% haircut to par. The pre-transaction OpCo senior secured notes total of €1,470mm was distributed into €693mm of 1L notes, €240mm of 2L notes, and €241mm in preferred shares. A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows the lenders took about a 20% haircut as the post-conversion amount of €1,174mm is around 80% of the €1,470mm face value. Additionally, the claim converted into HoldCo preferred shares was effectively demoted in the capital structure, sitting structurally junior to the debt and ranking pari passu with KKR’s position.

The transaction also provided substantial cash flow relief by converting interest obligations into Payment-in-Kind (PIK). Specifically, the new Second Lien notes (10% interest) and the Preferred Shares (12% dividend) were structured as 'PIK-only' instruments, meaning interest would accrue to the principal rather than being paid in cash, thereby effectively pausing significant debt service outflows.

Figure 3: Pre and Post 2020 Transaction Cap Table

There was one tranche of senior secured 1L notes prior to the transaction (€1,470mm), which was bifurcated into two tranches post transaction (€693mm 1L and €240mm 2L notes). The capital injection was crucial in extending the runway to navigate the immediate post-pandemic environment. The existing senior secured notes (previous maturity) were exchanged for new 1L and 2L notes maturing in 2026. To implement this transaction, Selecta utilized an English Scheme of Arrangement under the Companies Act 2006. As the group was initially Netherlands-based, this required adding a new co-issuer called Selecta Finance UK Limited to the debt silo. This UK entity became the co-issuer (alongside the original issuer, Selecta Group B.V.) of the new Senior Secured First Lien Notes and Senior Secured Second Lien Notes (both maturing in 2026). Through this structure, Selecta was able to access the English High Court and bind all creditors to the deal with a 75% voting threshold [5].

It is worth briefly exploring the English Scheme of Arrangement and the legal maneuvering utilized by Selecta. To create a sufficient connection to the UK jurisdiction, which is a prerequisite for the English courts to accept the case, Selecta amended the governing law of its debt documents to English law, and it also added a newly incorporated UK entity as a co-issuer of its notes. The benefit of this structure was that Selecta was able to work within a more creditor-friendly regime, securing the necessary 75% approval and combining its pan-European creditor base. The Netherlands (the alternative) lacked a robust pre-bankruptcy restructuring tool equal to the UK Scheme. Furthermore, without accessing the UK, Selecta would likely have had to execute a fragmented transaction across multiple jurisdictions or required unanimous creditor consent (a big hurdle given the diverse creditor base).

Figure 4: Simplified Org Chart at 2020 Transaction

Failed Recovery and Emergence from COVID-19

The 2020 transaction was designed as a bridge to a post-COVID recovery that ultimately never materialized as planned by management. The transaction solved the impending liquidity crisis via the KKR facility and converted cash interest to PIK. The fundamental problem with this conversion was that the outstanding debt principal ballooned while the business failed to recover operationally. At its crux, the 2020 transaction implicitly assumed a quick return to pre-COVID-19 work habits and significantly underestimated the persistent impacts of the pandemic. At the time of the deal, the company expected adjusted EBITDA to increase from €128mm in 2021 to €224mm in 2024, and estimated leverage to get down below 8x [4].

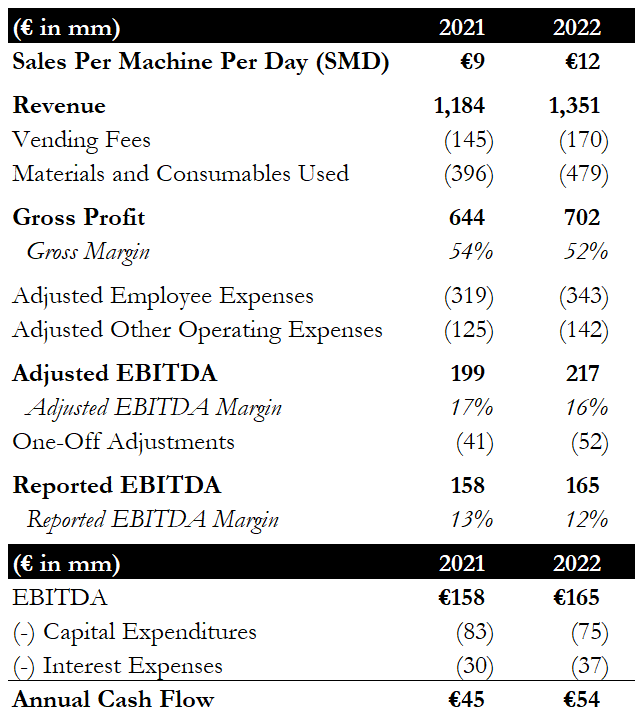

As shown in the figure below, the slow recovery in the top-line was not translating to meaningful free cash flow conversion. While reported EBITDA grew to €165mm, annual cash flow remained relatively flat at around €54mm. It is important to note that the interest in the figure refers to cash interest paid, so it ignores the massive PIK interest that was slowly accruing on the balance sheet. Essentially, the strong bifurcation between cash generation and the debt pile meant that the business could not climb out of its troubled capital structure.

Figure 5: Operating Performance During 2021-2022. SMD is calculated as Net Sales/Machines/Working Days.

Following the initial stabilization, the period from 2022-2024 was defined by a combination of stagnant volume and soaring costs. In 2022, the war in Ukraine caused a spike in input costs, exposing the vulnerability of Selecta’s cost structure. As a result, management implemented the Strategic Intentional Churn (SIC) policy, which focused on physically removing unprofitable machines to improve margins. This was a double-edged sword: while it helped improve margins, it shrank the absolute coverage/scale of the business, handicapping top-line recovery. By 2024, although the business had stabilized as a leaner entity, cash flow barely covered maintenance capex, leaving the compounding PIK interest to push the capital structure mathematically beyond the point of no return.

By 2025, Selecta faced a looming 2026 maturity wall with the 2026 notes approaching repayment. A fundamental reason behind the failed recovery in the zombie years (2021-2024) was that the high debt burden diverted significant cash flow from operations to debt service, which limited the ability of management to invest in necessary projects like telemetry and new machines. There were a few other reasons behind the failed recovery. First, rising materials and consumables costs significantly outpaced revenue growth. Second, a sharp rise in vending fees meant that landlords were capturing a larger share of the marginal revenue recovery.

Review of Key Transaction Elements

Before analyzing Selecta’s 2025 out-of-court transaction, it is crucial to first understand the specific legal maneuver used by the Ad-Hoc Group (AHG) to control the business post-restructuring.

You are about to reach the core of the report. This is where the story gets interesting.

Free readers miss out on the sections that explain:

• Key Transaction Elements

• The Co-op: The Glue Behind the Aggression

• June 2025 Out-of-Court Transaction

• Non-AHG Lender Choice and Exchange Math

• Transaction Analysis: AHG Control and Next Steps

• Conclusion

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive.

Reach us at [email protected] for a group subscription to avoid falling behind your peers.

Unlock the Full Analysis and Proprietary Insights

A Pari Passu Premium subscription provides unrestricted access to this report and our comprehensive library of institutional-grade research

Upgrade NowA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Full Access to Our Entire Archive

- 150+ Reports of Evergreen Research

- Full Access to All New Research

- Access to the Restructuring Drive

- Join Thousands of Professional Readers