Welcome to the 164th Pari Passu Newsletter,

Ahead of our year-end letter next week, today’s writeup marks our final restructuring deep dive of the year. This year, we’ve covered Extend-and-Exchanges, Hunter-Gatherer LMEs, and the growing trend of Sponsor Subordination. Today, we’re ending the year strong with a double-LME edition, diving into City Brewing, one of America’s largest beverage co-manufacturers. Over more than 150 years, the original City Brewery successfully capitalized on various alcoholic beverage trends, the most recent of which was the hard seltzer boom of the late 2010s. However, as these trends subsided, City Brewing’s new investors ran into serious trouble, eventually leading to two consecutive LMEs in April 2024 and August 2025.

This write-up is based on discussions with people familiar with the situation, which informed our market-sourced view of the company’s financial distress and ensuing transactions. This perspective was especially helpful in unpacking the dynamics of the dropdown and double-dip structure in the 2024 LME, and how it shifted value towards a select group of creditors. Some figures are based on market estimates and discussions and should not be interpreted as company disclosures.

We’ll dive into the risks of the co-manufacturing repobusiness model and detail the rich history of City Brewing. We’ll also cover the last 5-10 years of trends in the alcoholic beverage market, and how City Brewing ended up on the wrong side, before ending with an in-depth analysis of both liability management exercises and the path ahead for City Brewing’s new owners.

New AI Model Releases - What Does It Mean for Finance

OpenAI’s Project Mercury appears to be paying off. GPT-5.2 released Wednesday and scored 68% on junior investment banking tasks. These models appear to be powering Endex: OpenAI’s Excel agent.

Major Wall Street firms are rapidly adopting Endex for analyst tasks, as CEOs like Jamie Dimon warn that AI productivity gains will reshape finance teams and eliminate certain roles over the coming years.

They are also hiring additional bankers and analysts to train their agentic capabilities.

Contract Manufacturing Business Model

Before we dive into the history of City Brewing itself, it’s important to review the co-manufacturing business model and its inherent risks that played a role in the company’s distress.

Co-manufacturing, or co-packing, refers to a production model in which a third-party manufacturer produces and packages beverages on behalf of brand owners. In this structure, the co-packer owns and operates the physical manufacturing infrastructure, including brewing systems, bottling lines, quality control, etc., while the customer (beverage brand) provides the beverage formulation. The beverage manufacturing process is inherently quite complex, and the co-manufacturing business model shifts this burden from beverage brands to the dedicated co-packer.

Figure 1: The Beverage Manufacturing Process [1]

This model is attractive to brand owners because it dramatically reduces the capital requirements associated with beverage manufacturing. Instead of deploying millions of dollars to build brewing or bottling facilities, brands can outsource production and allocate capital towards product development, marketing, and distribution. This allows new beverage brands to scale quickly, as production can ramp up without the time investment required to construct and permit new facilities. Typically, using a co-packing model, new brands can move from an approved formulation to first production in 8-12 weeks [2]. This flexibility is especially attractive in trend-driven beverage categories such as hard seltzer, energy drinks, craft beer, and other unique ready-to-drink (RTD) beverage products, where rapid product launches can be critical for capturing market share.

On the co-packer’s side, this business model is extremely capital-intensive, as co-packers must build and maintain large, highly regulated brewing facilities. This presents its own set of risks and rewards. In terms of rewards, the co-manufacturing business model offers quite attractive economics when facility utilization is high. Once fixed costs associated with plants, labor, and equipment are covered, incremental production typically carries relatively high contribution margins, allowing co-packers to benefit from economies of scale. In an environment of strong and stable demand, co-manufacturers can have a quite attractive cash flow profile.

However, this model is not without risks. First, co-packers are highly dependent on their customers' performance and the durability of consumer trends. Because they do not own the brands they produce, co-packers have limited control over end-market outcomes. Instead, they rely solely on forecasted demand and order sizing from their brand customers. Therefore, a co-packer’s revenue is indirectly tied to the success or failure of third-party brands and shifts in consumer or retailer preferences.

Client concentration amplifies this risk. Typically, large co-packers rely on a small number of large anchor customers to keep utilization high and steady, as this reduces the uncertainty and incremental costs associated with switching between a larger number of smaller brands. However, the loss of a single major contract or a large reduction in order size can serve as a serious detriment to the economics of co-manufacturing.

The third risk relates to the size of the customers that co-packers serve. Since well-established national brands typically have their own brewing facilities, co-packers thrive from emerging and mid-sized brands. In a trend-driven beverage market, emerging brands that grow in popularity can become a cash cow for a co-packer; however, when brands grow too large, co-packers risk being insourced. Additionally, if emerging beverage brands don’t take off within a couple of years, they separate from the winners, reducing order size and eventually shuttering altogether. The client attrition factor from smaller brands can add unplanned capital requirements, as co-packers must reconfigure manufacturing lines to meet new brands’ needs. Therefore, successful co-packers must strike a balance, finding stable midsize brands.

G. Heileman Brewing Company

Now that we’ve overviewed City Brewing’s co-manufacturing business model, let’s get into the history of the company itself.

City Brewing’s original location was established in 1858 in La Crosse, Wisconsin, by German immigrant Gottlieb Heileman. Heileman used this facility to found the G. Heileman Brewing Company, which originally focused on using water from the Mississippi River to develop lagers (a type of beer) popular with German immigrants in the area [3].

Over the next century and a half, the G. Heileman Brewing Company would remain under Heileman family ownership. The company grew rapidly via a series of acquisitions, acquiring nearly two dozen other regional breweries. In 1956, the company ranked 39th among US breweries. During this period, the company was primarily producing its own branded beer, occasionally using co-manufacturing to fill excess capacity. By 1983, after several more pivotal acquisitions aimed at national expansion, the company was the fourth-largest US brewery, with annual sales exceeding $1bn [3].

However, as the broader brewing industry continued to consolidate, G. Heileman faced increasing competition, which eventually led to the company’s sale to the Stroh Brewery Company, the third largest brewery behind Anheuser-Busch and Miller.

However, after just three years, Stroh, having failed to compete with national brands, underwent a fire sale of its brands and assets in 1999.

City Brewing

During the 1999 sale, the flagship LaCrosse facility (the original G. Heileman brewery) was acquired by the investment firm Platinum Holdings (no, not Platinum Equity) for $10.5mm, just a few months after it was closed. Under new ownership, the LaCrosse facility was established as City Brewing. Unfortunately for Platinum, after failing to gain traction, the new company defaulted on a $4.5mm loan used to fund the acquisition and was foreclosed on [3].

In November 2000, another group of investors, led by future City Brewing president Randy Smith, raised $9mm to acquire City Brewing and the LaCrosse facility out of foreclosure. Finally, the new investor group was able to fully return to production, employing 185 people by mid-2001. By 2002, the company was producing at least 1.2mm barrels (31 gallons each) of beverage annually. Notably, while City Brewing did still operate several of its own legacy beer brands, upwards of 98% of production was done under co-manufacturing agreements, with an early notable customer being Arizona Iced Tea [3]. This agreement also reflected City Brewing’s new strategy of diversifying beyond beer into other RTD beverages.

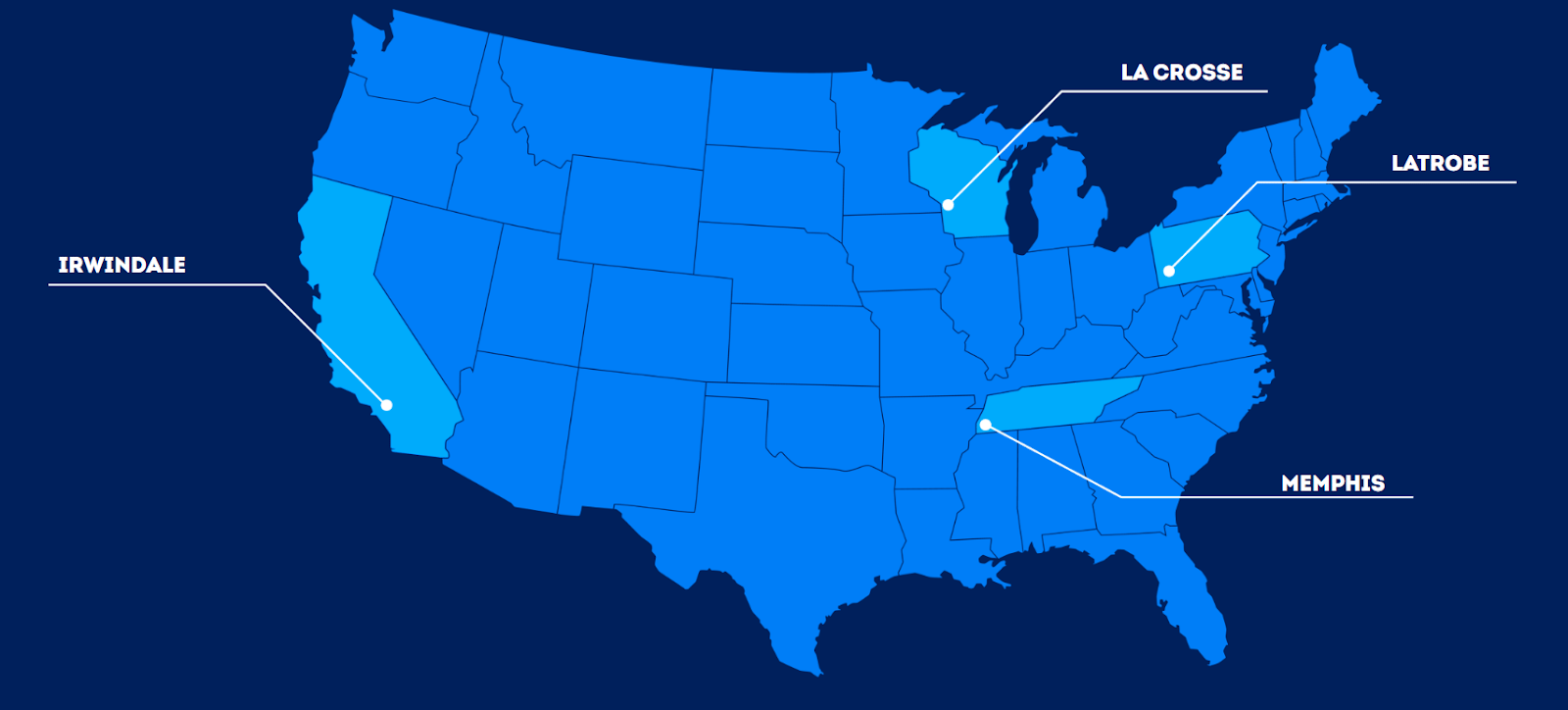

Over the next decade, as City Brewing continued to grow as a powerful regional co-packer, the company also acquired two more facilities. In 2006, it acquired the former Latrobe Brewing Company plant in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and in 2011, it acquired a brewing plant in Memphis, Tennessee, previously operated by Molson Coors (a large national brewery). City Brewing stated that the Memphis acquisition expanded its total brewing capacity from 6mm to 10mm barrels annually, nearly 10 times what the company was producing a decade earlier [4]. For reference, Bud Light, which at the time was the largest American beer brand, produced 47.4mm barrels in 2010 [17].

2021 Buyout

Throughout City Brewing’s expansion period, Blue Ribbon Partners, the owners of Pabst Brewing, a key customer of City Brewing, had been building a meaningful equity stake in the company. In 2021, a new consortium of investors, including Oaktree Capital Management, Blue Ribbon Partners, Charlesbank Capital Partners, and existing management, among others, acquired 100% of City Brewing's equity from its legacy shareholders, primarily founder-owners [5]. Through our research, Pari Passu sources said that Blue Ribbon rolled $450mm of equity in the transaction, while new equityholders contributed $400mm [0]. The recapitalization was also funded via an $850mm term loan, which, in total, implied valuing City Brewing at $1.64bn TEV or 8.5x PF adjusted EBITDA of $193mm.

Figure 2: The 2021 Buyout [0]

Following the transaction, City Brewing also announced a new $630mm investment program, which aimed to capitalize on the growing craft beer and hard seltzer markets by growing capacity from 10mm barrels in 2021 to 20mm in 2025 [0]. The largest part of this investment program was the acquisition of a brewery in Irwindale, California, from Pabst Brewing Company (which was owned by Blue Ribbon). While the specific sale price of the facility is not public, Pabst purchased it from Molson Coors in 2020 for $150mm, and people familiar with the matter said that the price remained in that range [0].

The impact of this expansion was twofold. First, it was projected to nearly double City Brewing’s capacity from 130mm cases (~10mm barrels) to 240mm cases (~17mm barrels). This additional capacity allowed City Brewing to become the primary co-packer for multiple new national brands, including Pabst, which announced the movement of a majority of production to City Brewing’s facilities by 2024. The second impact was geographical, as the Irwington expansion provided a key touchpoint into the Western US. City Brewing could now practically co-manufacture for most, if not all, of the continental US.

Figure 2: City Brewing’s Geographical Footprint

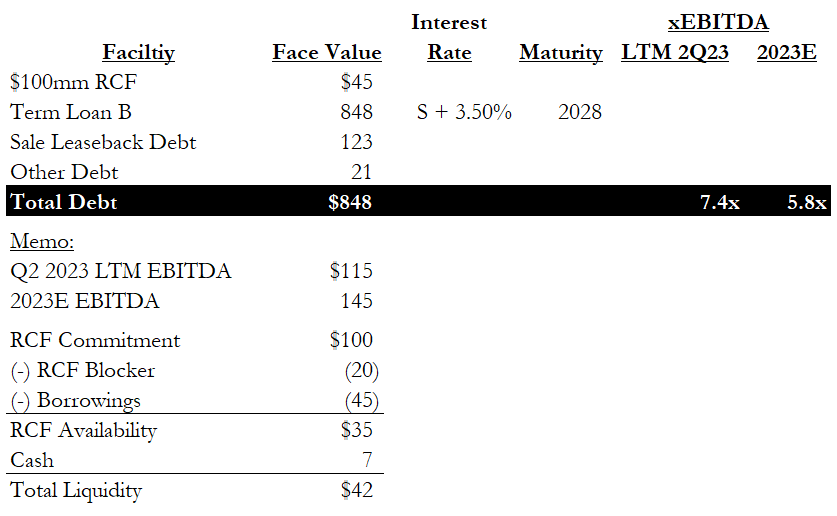

To put some perspective on City Brewing’s financials, we’ll first look at their total debt following the 2021 buyout. In conjunction with the deal, the company issued a $850mm term loan B, due 2028, and priced at SOFR + 3.50%, as well as a $122mm RCF, due 2026, priced at S + 3.25%. At the time of the transaction, based on $175mm of 2021 Adj. EBITDA, leverage was roughly 5x [0].

The RTD Bev Market: Boom and Bust

At the time of the 2021 transaction, the alternative alcohol market, particularly hard seltzers, was at the peak of its growth. From 2018 to 2021, the total hard seltzer market more than quadrupled, from $2.4bn to $11.3bn, representing a ~70% CAGR [7]. This provides a strong rationale for the $630mm investment program, meant to expand beyond beer into categories like hard seltzer.

Unfortunately for City Brewing’s new investors, these plans would begin to unravel as the hard seltzer market’s growth decelerated rapidly in 2021, as it became saturated and consumers shifted to other alternative alcohols, such as RTD spirits. At the same time, various national alcohol brands diluted the hard seltzer market by launching their own versions. While City Brewing did not publicly report financials, people familiar with the situation described the following financial picture. To start, people familiar with the situation described $175mm of 2021 Adj. EBITDA and $110mm of unlevered cash flow before capex [0]. After accounting for substantial capex spend of $190mm, reflecting the aggressive facility investment program, true unlevered FCF was -$75mm [0]. With SOFR near zero, City Brewing was footing just $35mm of TLB interest expense at the time, bringing total cash burn in 2021 to -$110mm. While City Brewing was spending cash to increase capacity, it was losing business at the same time. Outside of the market-wide headwinds the company faced, White Claw, the single largest seltzer brand at the time and a key City Brewing customer, opened a $490mm brewery in 2022 and began shifting production there [9]. This shift provides a great example of the risks to the co-packing model we detailed above, which is simply being outgrown by the successful customers who initially propelled the business.

The next year painted a very similar picture for City Brewing: hard seltzer and craft beer demand continued to decline, and with it, the company’s operational performance. As facility utilization continued to fall, City Brewing struggled to shed fixed costs, and EBITDA continued to experience outsized declines. This strain became most evident in Q1 2023, when the company broke its 7.15x leverage covenant on its RCF, reporting leverage of 8.95x [10]. With ~$1,050mm of total debt (including leases and other debt), this implies LTM EBITDA of $117mm. With just $14mm of cash on hand, the company was forced to negotiate, and lenders agreed to waive the requirement through Q4 2023.

Another variable taking shape for City Brewing was interest rate pressure. By mid-2023, SOFR had reached its peak of roughly 5.25%, raising City Brewing’s effective TLB rate from 3.50% to 8.75%. On $850mm of TLB debt, this corresponds to an increase in interest expense from $30mm to $74mm. When adding interest on the $77mm RCF draw, this burden increases to roughly $84mm. Critically, this represents over 70% of EBITDA we estimated above, but despite liquidity pressure, City Brewing continued to pour cash into facility improvements and capacity expansion, with estimated capex between $40mm and $80mm. Assuming $50mm of capex, the company would have been burning $30mm of cash annually.

Instead of turning to lenders, City Brewing funded this cash shortfall via a series of equipment sale-leasebacks, totalling $133mm from 2022 to 2023, using proceeds to fund capex and pay down the RCF. This strategy was particularly concerning for lenders, as City Brewing’s collateral base primarily consisted of its brewing and packing equipment. As a result of these sales, City Brewing’s $850mm TLB rapidly declined to the low 40s in May 2023[10]. This implied just ~$400mm of enterprise value (~4x EBITDA), representing a massive decline in lender confidence.

2024 LME

According to Pari Passu sources, we’ve put together an estimate of City Brewing’s 2023 financial profile. The factors outlined above had caused Q2 2023 LTM EBITDA to deteriorate to $115mm. However, by Q3 2023, City Brewing’s operating performance had begun to stabilize, with 2023 EBITDA projected to rebound to roughly $145mm as utilization improved under new contracts [0]. Importantly, this brought the company back into compliance with its leverage covenant, with 2023 leverage now sitting at 5.8x. Despite an improvement in EBITDA, City Brewing still faced significant cash flow pressures. Ramping up production for new contracts can require considerable modifications to production lines, as different beverages have quite different equipment requirements. The EBITDA improvements from new manufacturing contracts were offset by the capital needed to ramp up production.

Figure 3: Capital Structure as of August 2023 - Illustrative Estimates

As a result of these capital requirements, along with the significant interest burden detailed above, total Q3 2023 liquidity still sat at just $42mm, as City Brewing struggled to convert EBITDA into cash [11]. With $145mm of EBITDA and $84mm of interest expense, we estimate that City Brewing likely burned cash through the rest of 2023 and H1 2024, reflecting a capex figure toward the upper end of management’s $40mm to $80mm range.

Figure 4: Capex-Driven Cash Burn - Illustrative Estimates

By April 2024, after continuing to burn cash, City Brewing was in desperate need of liquidity, with $6mm of cash and $4mm available under the RCF, just $10mm of total liquidity, likely equating to just a few weeks of runway. However, City Brewing had likely exhausted its prior method of equipment sale-leasebacks, as lenders would no longer tolerate collateral leaking [10]. Instead, the company retained Evercore and Sullivan & Cromwell to explore a solution that would address the entire capital structure while raising the liquidity required to return to full utilization.

After negotiating with an ad hoc lender group comprising 73% of TLB holdings, City Brewing launched a distressed exchange, offered to all TLB and RCF lenders, on April 15th, aiming to close by April 24th [12]. The transaction, which featured elements of both a dropdown and double dip, closed on April 26th, 2024. The structure is detailed below [12]:

Certain brewery assets were dropped down into a non-guarantor restricted subsidiary, referred to as BrewCo.

$115mm of new money raised in a first-out term loan, due 2028, priced at S + 6.25%, at the BrewCo level.

The New Money and subsequent new RCF draws were upstreamed to City Brewing (RemainCo) via an intercompany loan.

Ad Hoc TLB holders exchanged 50/50 at 97 cents into a first-out and second-out term loan, at the BrewCo level.

Other TLB lenders could exchange 40/60 into the first-out and second-out tranches at 85 cents, only if they participated in the new money offering.

The $115mm ($122mm incl. fees) of new money, raised at BrewCo, also benefited from a RemainCo guarantee, providing double-dip protection to BrewCo debt and diluting any holdout claims left at RemainCo.

Figure 5: City Brewing’s 2024 LME

Eventually, the transaction gathered 98% of TLB holders, leaving just 2%, or $15mm of TLB debt, held at RemainCo. These non-participating creditors were now structurally subordinated to participating creditors, as BrewCo held a majority of City Brewing’s valuable equipment and facility assets. In simple terms, in the event of a BrewCo liquidation, BrewCo's debt would need to be fully paid off before any value flows up to RemainCo. This effectively put all RemainCo debt out of the money.

Economically, the transaction served a few key functions. The first was the injection of $115mm of new capital. $78mm of this new money was used to pay down a substantial portion of the exchanged RCF, which, under the deal, had been upsized from $100mm to $120mm and extended by one year, leaving just $7mm in outstanding RCF borrowings following the transaction [0]. The remaining cash would be used to cover accrued interest payments and transaction costs. All in all, the transaction increased City Brewing’s liquidity from $10mm to $108mm, comprised of $6mm in cash and $102mm in remaining availability under the upsized RCF. At the company’s annualized cash burn rate of roughly $30mm, this RCF provided more than three years of projected runway. Importantly, this deal also eliminated the leverage covenant that had previously troubled City Brewing. Lastly, while the deal did capture $50mm of discount, total debt only dropped by $6mm, holding leverage at an aggressive 7.2x 2024 EBITDA of $146mm.

Continued Distress

Despite City Brewing’s improvements in liquidity, the transaction did nothing to solve the inherent volatility in its business model.

You are about to reach the midpoint of the report. This is where the story gets interesting.

Free readers miss out on the sections that explain:

• December 2024

• 2025 Transaction

• Go-Forward Lender Options

• Recovery Analysis

• Key Takeaways and Much More

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive.

Get your employer to pay, Reimbursement / Approval Email Template here.

Unlock the Full Analysis and Proprietary Insights

A Pari Passu Premium subscription provides unrestricted access to this report and our comprehensive library of institutional-grade research

Upgrade NowA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Full Access to Our Entire Archive

- 150+ Reports of Evergreen Research

- Full Access to All New Research

- Access to the Restructuring Drive

- Join Thousands of Professional Readers