Welcome to the 154th Pari Passu Newsletter,

We’re super excited to bring you Part 2 of our Thames Water series, a comprehensive deep dive into one of Europe’s most consequential workouts ever! If you missed Part 1, start there. We set out the 1989 privatization, Ofwat’s model (RCV, WACC, ODIs and ring fencing), and the ownership journey from RWE to Macquarie’s whole business securitisation. That context shows how value extraction, regulatory limits, and underinvestment laid the ground for today’s crisis.

In Part 2, we get into the nuts and bolts of the ongoing restructuring. We dive deep into the company’s multi-layered capital structure, which reveals a key driver of distress only really found in the UK. From there, we present our narrative of the roller-coaster that Thames Water has been through since 2023: shareholders backing out, cash lock-ups, parent companies’ defaults, and increasing government and regulatory intervention.

This will be one of the most unique restructuring stories you will ever read!

But first, a way to efficiently handle K1s and your taxes

I firmly believe that one of the most underrated benefits of working great buyside jobs is the ability to invest in funds that are usually reserved for Institutional Investors (often with backleverage and no fees, but that’s a discussion for another day).

The annoying downside? Getting K1s and seeing our tax filings get a lot more complicated. I have experienced this, and if you have not already, you will.

This is why, when Agent Tax reached out, I was so excited to learn more, and I am now excited to bring this service to you. Agent is a modern tax strategy firm purpose-built for investment professionals. You will receive a dedicated expert tax advisor (yes, human) who will leverage technology to proactively plan, prepare, and optimize your taxes.

Tax is everyone’s biggest expense, and this is a great service to minimize tax leakage. Click below to learn more with a free consultation and mention Pari Passu to get $100 off.

Recap of Part 1

Let’s recap Part 1 and the story so far. We began with the privatization of the entire water sector in England & Wales in 1989. We outlined three major themes that have and will continue to run through our story: (i) water and sewage service providers are typically natural monopolies, (ii) the absence of competition means incentives for shareholders are misaligned with customers’ and the environment’s interests, and (iii) the need for a regulator to act as a substitute for competition and to ensure public needs are met.

We then learned about the UK’s water regulator, Ofwat. There we produced a mental model to understand what is otherwise a complex regulatory framework: (i) Ofwat sets price limits for customer bills, (ii) one of the most important factors in price setting is determining what constitutes fair or allowed returns (estimated WACC x Regulatory Capital Value (RCV), the asset base subject to regulation) (iii) Outcome Delivery Incentives and (iv) Ofwat’s ringfencing rules, which trap cash in the operating company if credit ratings fall below Baa2. We then covered the RWE ownership period from 2001 to 2006, where we saw debt loaded onto Thames, but in the parent companies above OpCo, and over £1bn of dividends extracted by the ultimate German parent.

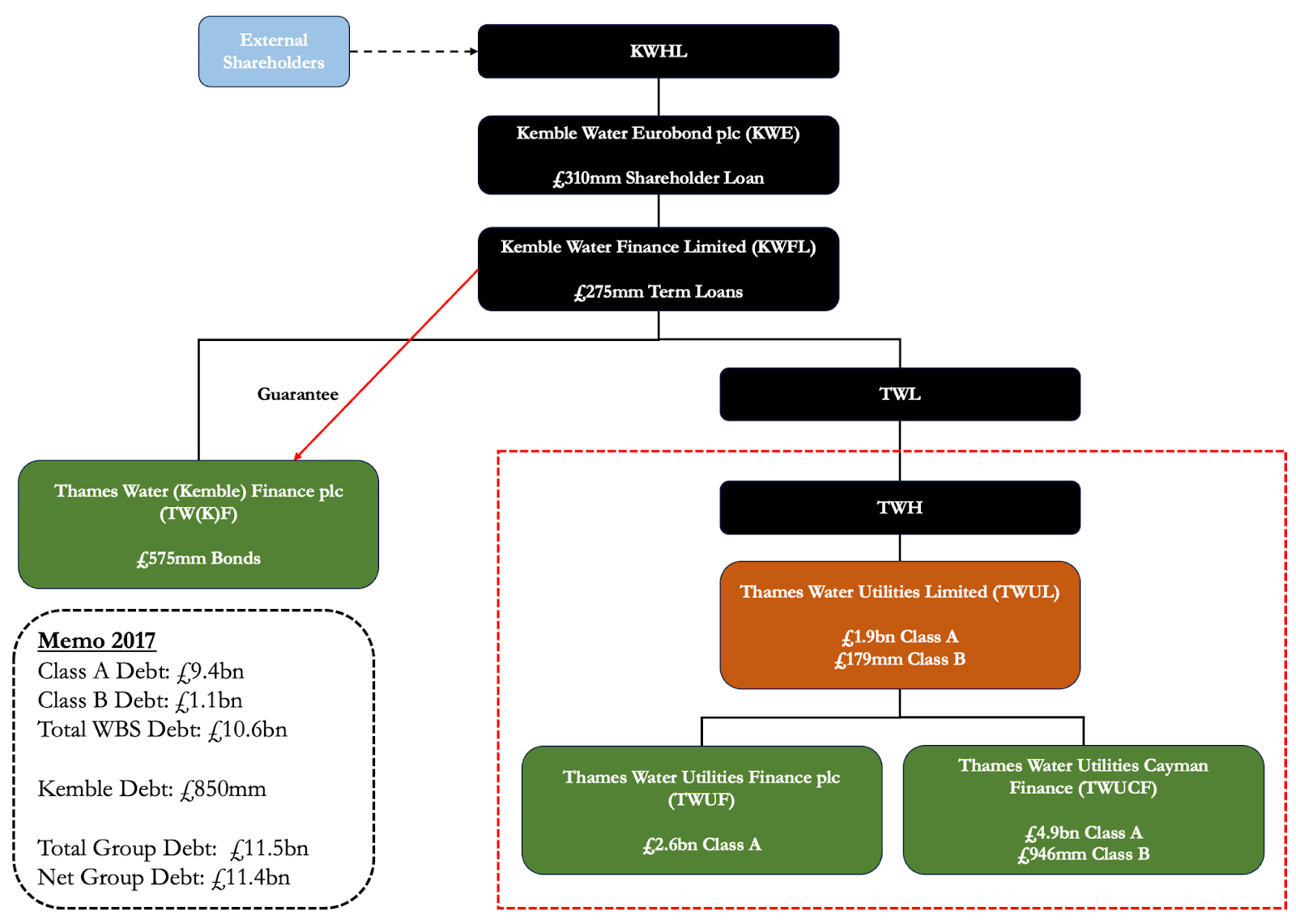

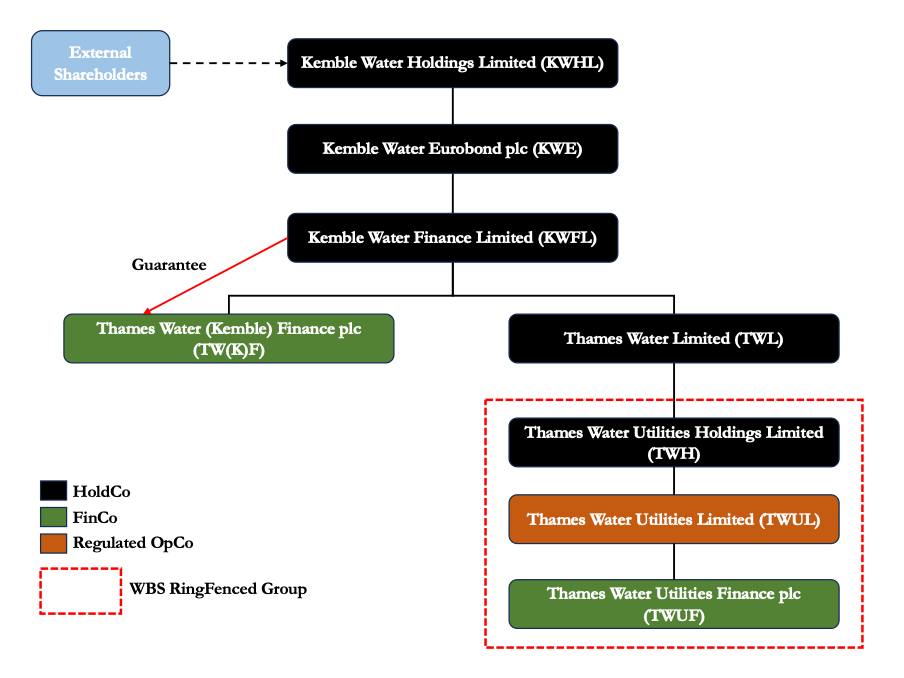

Next came Macquarie in late 2006, which sparked the most consequential period for Thames’ present day crisis. They first put in place a Whole Business Securitization (WBS), and we broke down the key terms of the Common Terms Agreement (CTA) which governed the structure, binding all creditors across different instruments under one unified set of rules in the WBS. We also saw the host of parent companies outside of the ring-fence: the Kemble Group. By 2017, this complex corporate structure protected Thames’ credit ratings and allowed Macquarie to redistribute and load debt onto the WBS (£2bn to almost £11bn) and extract £1.2bn in dividends and interest payments, all while missing several performance targets. And so, we left off with Thames looking very shaky, its statutory Gearing Ratio (RCV/Net Debt) at 83% and its Post Maintenance Interest Cover Ratio (PMICR) at 1.7x.

Macquarie exit 2017

In March 2017, Macquarie completed its exit from Thames Water, selling its remaining 26.3% stake in the ultimate parent, Kemble Water Holdings Limited (KWHL). The buyers were Borealis Infrastructure (OMERS) and Wren House (Kuwait Investment Authority), who joined other long-term pension and sovereign investors already on the register [3]. Structurally, as the deal was an equity sale at the Kemble level, Thames Water’s debt stack remained untouched.

In contrast to Part I, we are going to delve even deeper into the financial information Thames was publishing. We will move away from using statutory Net Debt to ‘covenant basis’ Net Debt. Some debts, like shareholder loans and certain intercompany loans, are not included in how Net Debt is defined in the Common Terms Agreement (CTA). This will provide us with the most accurate information on Thames’ financial health assessed against its covenants.

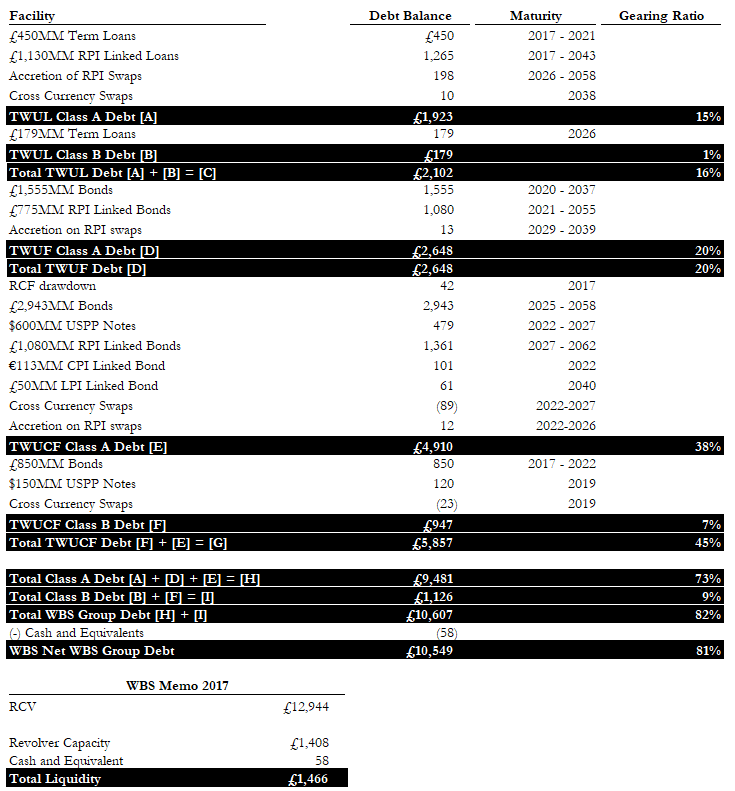

Below is a cap table for the WBS entities. Due to the refinance risk mitigation clauses in the CTA, Thames’ capital structure is complex and consists of several different types of debt instruments across various entities. So, to help you make sense of Thames’ financial position, we have consolidated its capital structures, included corporate structure charts with debt labeled, and pulled debt maturity profiles. Let’s go through WBS’s capital structure first.

Figure 1: WBS 2017 Debt Capital Structure [1] [8]. Note for revolver capacity, the RCFs are included inconsistently across annual and investor reports, so we only include total revolver capacity in memos.

You may have noticed that when looking at the cap table that the RPI-linked loans and bonds, their ‘debt balance’ is often significantly higher than their face value. For example, £775mm Class A RPI Bonds issued by TWUF had a debt balance of £1,080mm. The debt balance is the outstanding principal due, and in Thames’ case, has been increasing without any additional borrowing. The reason for this is that a significant portion of WBS debt is inflation-linked.

Inflation-Linked Debt is where the principal and interest payments rise with consumer prices. The face value of the debt will track an inflation index, and the interest payments will rise accordingly as a fixed percentage of this increasing principal [4]. RPI stands for the Retail Price Index, which is a measure of price inflation that, unlike CPI, includes mortgage interest payments, housing-related costs, council taxes, etc [5]. It is the inflation measure used on most of Thames’ indexed bonds.

The obvious advantage for investors is that it ensures their income streams do not lose value over time. Should inflation rise, the principal and interest they are owed rise accordingly. But why are they popular for water companies? Well, customer bills are tied to inflation. Within a five-year Asset Management Plan (AMP) cycle (the period between the water regulator’s price reviews), water prices move with inflation after the price review is complete. This allows the water company to hedge against fluctuations in earnings due to inflation [2]. Combined with the fact that there is no need to compensate investors for the risk of future inflation spikes eating into their returns, index-linked debt was attractive for water companies like Thames [2].

However, it is not a perfect hedge. From 2020 onwards, Ofwat only allowed customer bills to rise annually by CPI + H (housing costs), which normally is lower than RPI [6] [7]. This means debt accretion from inflation will generally be higher than the customer bill increases. Thus, if there is a significant spread between CPI + H and RPI, then that is problematic for Thames [6].

So there’s another reason now why Thames has so much debt! Between Part 1 and Part 2 thus far, we have highlighted why WBS debt has been increasing, and we assessed its gearing ratios, interest coverage, and credit ratings. However, it is time to ask the most important question: when is all this debt falling due?

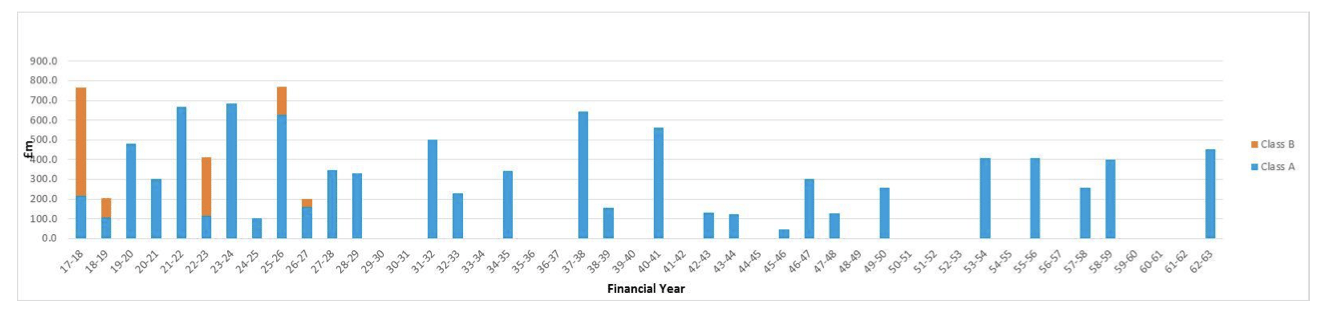

Figure 2: WBS Debt Maturity Profile 2017 [1].

Immediately, you will see that in 2017, there is a massive maturity wall. This mostly consists of the Class B £550mm Series 8 Bond that is maturing in July 2017. This was shortly refinanced right after FY 2017 into a Class B £300mm 2023 Bond and a Class B £250mm 2027 Bond.

Other than this, we can see how most of the debt is bunched up in the 2020s. Despite the refinance risk covenant in the CTA (recall that additional debt issuance cannot cause net debt to exceed 20% of RCV in any 24-month period or 40% of RCV within any five-year AMP [1]), approximately £4.5bn of the £10.6bn WBS falls due in the next nine years.

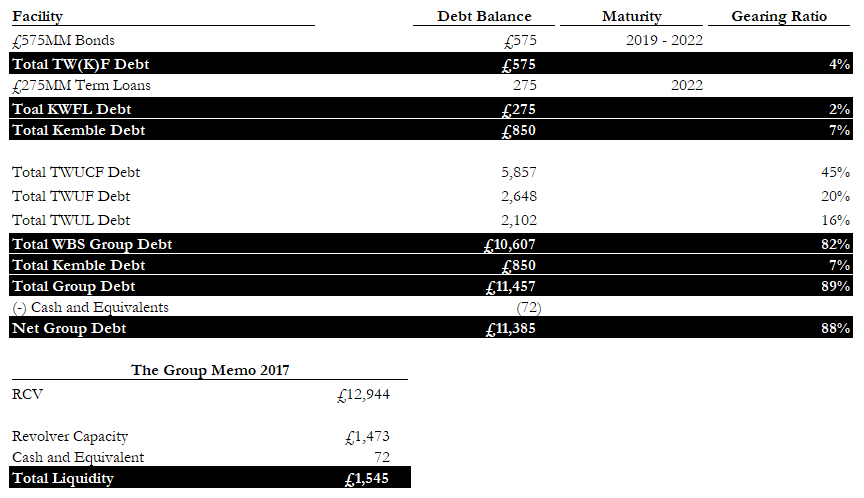

Finally, let’s have a look at the Group’s capital structure, including the Kemble companies

Figure 3: The Group 2017 Debt Capital Structure. Shareholder loans to Kemble Eurobond are excluded as it does not count towards Debt on a covenant basis [1] [8].

Figure 4: Corporate Structure Chart 2017 with Debt [1] [8].

The group carried £11.4bn net debt, and over 93% of it was pushed down into the WBS structure. The holding companies added only a thin layer on top, leaving the WBS to shoulder virtually the entire burden. With net debt almost identical to gross and cash buffers negligible, the balance sheet was already stretched.

Reaching a Boiling Point FY 2017 – FY 2023

Before we look at the numbers, in early 2018, Thames moved to close its Cayman Islands finance subsidiary (TWUCF) [11], which had become politically toxic even though those offshore entities produced no direct tax advantage [12] [13]. All bonds were refinanced and effectively transferred to TWUF.

Figure 5: New Group Corporate Structure in FY 2019 after TWUCF’s closure [12]

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Full Access to Over 300,000 Words of Evergreen Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Access to the Restructuring Drive