Welcome to the 162nd Pari Passu newsletter.

A few months ago, we wrote about how the ad-hoc group of ATD’s litigious non pro-rata roll-up DIP structure conceded their DIP financing contention with a full resolution, choosing not to pursue future contract litigation. Ultimately, as the threat of litigation overhang continues to strongly influence the options that distressed companies choose to pursue out-of-court and in-court, some lenders are opting to concede some value early to avoid prolonged future valuation, contract, and other types of litigation inside and outside of Chapter 11. In essence, legal scrutiny provides some deterrence to aggressive outcomes.

Why? On one hand, a prolonged bankruptcy can be value-destructive to the estate due to high legal & professional fees, stricter vendor terms, customer attrition, employee turnover, and many other reasons. On the other hand, aggressive and litigious LMEs that are subsequently invalidated may leave participating creditors with poor recoveries, unless downside protection like an unwind remedy has been added. Consequently, as in the case of Weight Watchers, lenders may seek to accelerate bankruptcy and protect some theoretical going-concern value of the debtor by making concessions to out-of-the-money stakeholders in a rough justice trade.

In today’s write-up, we will discuss Weight Watchers’ prolonged path to bankruptcy, its restructuring options, and why it chose to pursue a prepack Chapter 11 rough justice outcome. Let’s dive in.

Before we get started, a quick administrative note: we now allow group subscriptions and signed the first group subscription with an investment firm. If your firm is interested in bulk discounts, please reply to this email. Please note that I will refund you in full for your premium subscription if your firm subscribes! Very exciting things ahead for Pari Passu.

Join 9fin to discuss the art of the LME: tactics and precedent that defined 2025, and what’s coming next

On December 9, 9:30am ET, 9fin’s resident LME expert, Jane Komsky, will sit down with a star studded virtual panel to discuss:

Pro rata vs. non pro rata structures and how issuer-friendly approaches tipped the scales while lenders mounted their defense

Tiered participation and cooperation agreements that defined creditor treatment structures throughout 2025

Antitrust litigation in lender co-ops and where the line sits between collaboration and collusion

Early process NDAs and how information asymmetry is being weaponized before deals even go live

Speakers include:

Gregory F. Pesce, Partner, White & Case

Shai Schmidt, Partner, Glenn Agre

Adam Shpeen, Partner, Davis Polk

Stephen D. Silverman, Partner, Gibson Dunn

Joe Zujkowski, Partner, Latham & Watkins

Jane Komsky, Head of LMEs at 9fin

We are offering qualified Pari Passu subscribers access to a 45 day free trial of 9fin — that’s 15 days longer than usual. Click here to access the offer and sample some of 9fin’s latest coverage.

Weight Loss Management Industry Overview

The global weight management industry is broad and highly fragmented, shaped by shifting consumer preferences, medical advances, and low barriers to entry. At its core, the sector encompasses a large breadth of products and services to address the growing need for weight-loss solutions in an environment where over 40% of U.S. adults are considered obese and global obesity rates continue to climb [1]. Companies in this space face the challenge of adapting to consumer expectations that change every few years, often driven by cultural trends, social media influence, or scientific developments. With low barriers to entry, market adaptability remains at the forefront of a company’s long-term success in the industry, where science, technology, and culture continue to shift sentiment and definitions.

Post WWII, the industry was dominated by behavioral-based programs that relied on structured support systems to encourage gradual lifestyle changes: weekly workshops, calorie tracking tools, and peer accountability. Their success was reinforced by decades of published research in the 1970s-1990s showing that structured programs, including those of Weight Watchers, founded in 1963, produce more sustainable results than self-guided attempts. Consumers valued the sense of community and accountability, and for a time, behavioral programs became the default option for those seeking long-term weight loss.

As the industry expanded, new products and services emerged in the 1970s-1980s to complement or compete with behavioral models. Diet pills, nutritional supplements, and prepackaged meal kits grew popular as lower-commitment alternatives, while companies like Jenny Craig (founded in 1983) and Nutrisystem (founded in 1972) centered their businesses on meal replacements and coaching. These additions broadened the definition of weight management, transforming it into a consumer-products business as much as a behavioral health service. The result was a crowded, competitive landscape where consumers could choose from structured group programs, self-directed retail products, or medically supervised diets.

The next major evolution came with technology in the early 2000s. The rise of calorie-tracking apps, fitness wearables, and online communities gave rise to a new form of “Do-It-Yourself” (“DIY”) weight loss. Apps like MyFitnessPal, founded in 2005, allowed users to log meals, count calories, and monitor exercise for free, while platforms like Instagram and TikTok amplified diet fads ranging from intermittent fasting to keto. This shift gave consumers access to tools that were both costless and flexible, eroding some of the advantages that paid programs had long enjoyed. Legacy companies that had built their models on exclusivity and structured support suddenly found themselves competing against free, digital-first alternatives powered by influencer culture. COVID would significantly propel these digital-first competitors popularizing on social media.

However, the arrival of GLP-1 medications in 2017, but rapidly popularized in the COVID and post-COVID era, marked the most disruptive turning point in the industry to date. Drugs such as semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Zepbound) achieved double-digit body weight reductions in clinical studies [2], fundamentally altering consumer expectations around weight loss. While behavioral programs had promised steady progress, GLP-1s offered rapid and significant results, reframing dieting as a medical problem with a pharmacological solution. Side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and gallbladder disease or pancreatitis did not diminish demand, as millions of prescriptions were written within just months of launch [3]. Even today, the market for GLP-1 drugs continues to remain supply-constrained, not demand-constrained.

This rapid adoption gave rise to telehealth providers offering quick online consultations and monthly subscriptions to secure access to GLP-1s. Companies like Ro, Hims, and even traditional pharmacies moved into the space, creating an environment where consumers could access prescription drugs with relative ease. The cost of GLP-1s, though declining, is still meaningful: ~$499/month before any health insurance, declining insurance coverage, continuous drug intake, and incremental telehealth provider costs [4] [44]. Yet the tension remains clear: behavioral programs emphasize long-term habit change and holistic health benefits, while GLP-1s promise faster results but carry medical risks [5] and long-term cost burdens.

Founding and History

Weight Watchers traces its “human-centric” origins to 1961, when Jean Nidetch, a homemaker from Queens who had long struggled with her own weight, began inviting friends into her apartment for weekly support meetings. Nidetch once exclaimed, “compulsive eating is an emotional problem, and we use an emotional approach to its solution.” [6] This philosophy, anchoring weight management in accountability, shared experience, and behavioral change, became the bedrock of Weight Watchers.

The model quickly resonated. By 1963, the first large public meeting drew 400 attendees, and with the financial backing of fellow participants Al and Felice Lippert, Nidetch formally launched Weight Watchers Inc. The trio rented a movie theater in Queens for meetings, charged a modest $2 weekly fee, and reinvested proceeds into growth. The company’s model was intentionally self-reinforcing: many lecturers and group leaders were themselves successful Weight Watchers alumni, further deepening credibility and relatability.

Figure 1: Jean Nidetch leads a Weight Watchers meeting in the 1960s [7]

Within five years, Weight Watchers had expanded nationally and abroad through a franchise system. By 1968, it operated 91 franchises across 43 states and ten international markets, boasting over one million members. The company also diversified early into branded cookbooks, videotapes, and packaged low-fat foods, and even launched a syndicated television program, Weight Watchers Forum. This multi-pronged expansion helped solidify Weight Watchers as both a program and a consumer brand, embedding it deeply into American diet culture and culminating in an IPO that same year to fuel further growth.

Nidetch stepped down as company president in 1973, though she remained a public face of the brand. In 1978, H.J. Heinz acquired Weight Watchers for $71.2mm [8]; and, under Heinz, the program’s consumer product line expanded significantly, with branded frozen meals and snacks gaining a foothold in grocery stores worldwide. This era cemented Weight Watchers not just as a meeting-based program, but as a household name with reach across multiple consumer touchpoints.

The company’s most important product innovation arrived in 1997 with the introduction of the proprietary Points Program. Rather than asking members to count calories or follow rigid restrictions, the Points system translated nutritional information (calories, saturated fat, protein, fiber, etc) into a single, user-friendly metric. Each member received a personalized daily Points allowance, and each food was assigned a Points value based on its nutritional content. The simplicity of the Points framework, combined with the behavioral support of meetings, dramatically increased adherence and became the backbone of Weight Watchers for more than two decades.

Ownership of the company shifted again in 1999, when Heinz sold its stake to Luxembourg-based private equity firm Artal Group. Under Artal, Weight Watchers launched its first digital tools, returned to public markets in a 2001 IPO to raise ~$417.6mm ($24/share for 17.4mm shares offered), and operated for many years as a “controlled company” under exchange rules. Artal gradually reduced its stake beginning in 2018, retaining about 20% ownership into 2022 before fully exiting in 2023 [10].

The 2010s brought both challenges and rejuvenation. In 2015, Oprah Winfrey acquired an equity stake (10% ownership + an additional 5% of fully diluted stock options) and joined the board, providing one of the most high-profile celebrity endorsements in corporate history [11]. Her involvement reinvigorated marketing efforts and boosted subscriptions at a time when Weight Watchers was struggling with slowing growth. In 2018, the company rebranded to “WW” with the tagline Wellness that Works, an effort to reposition away from the stigma of “dieting” toward the broader, more holistic concept of wellness. [12]

Throughout its history, Weight Watchers’ credibility rested not only on its cultural visibility but also on its scientific foundation. Over the past four decades, more than 160+ peer-reviewed clinical studies have examined the program [13], with consistent findings that Weight Watchers participants lose more weight and maintain greater long-term weight reduction compared to self-help or DIY methods. This evidence base helped secure Weight Watchers’ standing as the #1 “Best Diet for Weight Loss” in U.S. News & World Report rankings for 15 consecutive years, a distinction that reinforced its reputation even as competition intensified [14].

By the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, Weight Watchers operated across 11 markets with millions of global members. Its hybrid model blended digital subscriptions through the WW app with in-person workshops led by more than 20,000 coaches, supported by branded consumer products and clinical programs. Yet its constant brand reinvention efforts underscored the fragile position of any behavioral weight-loss brand in an industry defined by low barriers to entry, fast-changing consumer sentiment, and increasingly disruptive alternatives.

Business Model

WeightWatchers (“WW”) operates as a subscription-based platform, offering three main tiers that blend behavioral support with digital tools; and, since 2023, a growing telehealth component. While WW operates across 11 global markets, 70% of its business derives from the United States. Ancillary revenue from product sales and licensing has largely disappeared, leaving subscriptions as the overwhelming majority of the company's revenue. Due to the highly seasonal (“New Year’s effect") nature of its business model, WW’s subscription count generally surges in Q1 of each fiscal year, and WW proceeds to aggressively market to retain those subscribers in Q2-Q4.

Subscriptions: WW generates subscription revenue, which accounts for ~85-95% of total revenue, through the monetization of its behavior-change programs via its (i) mobile WW app and (ii) supportive group sessions with trained coaches. Their offerings include one-on-one coaching and various programs such as the Diabetes Plan, a modified food program tailored towards Type one and two diabetics, and the GLP-1 Program, another modified plan that helps members prioritize nutritious foods while their appetite is significantly reduced by medication. The subscriptions are broken down into three groups:

Digital (core): Access to the Points program (incl. Diabetes and GLP-1–compatible pathways), tracking tools, recipes, and community. The cost is $23/month without any promotional rates or startup fees.

Workshops + Digital (premium): Digital features plus coach-led group sessions delivered virtually and in-person. This cohort shrank structurally as consumers shifted to digital-first usage and post-COVID studio closures continued [15]. The cost is $45/month without any promotional rates or startup fees.

Clinical (since Sequence acquisition in 2023 discussed later): Telehealth evaluation and ongoing monitoring for anti-obesity medications (when clinically appropriate). This service expands access to GLP-1 drugs when available by aiding customers in the prescription process. The cost is $74-84/month without any promotional rates or startup fees.

Other Revenues (formerly included e-commerce and product sales): Historically, WW sold branded consumables (snacks, bars) and studio merchandise (cookbooks, kitchen tools) through its e-commerce platform and studio locations; as studios closed/shifted and the brand deemphasized owned CPG, this line has shrunk materially from 17% of revenue in 2018 to ~1% of revenue in 2024 of. In 2021, consumer product sales only represented ~12% of the business, with international sales being unprofitable for the business [16]. As a result, WW discontinued consumer products sales in 2023, reducing overall brand visibility and shifting towards a pure subscription business model. Today, this segment is de minimis relative to subscription revenues and consists of revenues from licensing, franchise fees.

Figure 2: Revenue Breakdown in USD millions by Segment for each fiscal year. Given the Sequence acquisition in 2023, Clinical revenues only appear for fiscal years 2023 and beyond [21].

Path to Distress

The seeds of WW’s distressed situation were apparent before its Chapter 11 filing, as subtle cracks in the business model widened into structural problems. What began as a shift in subscriber behavior, WW’s problems would soon balloon to rising incumbents that would permanently reshape the weight management industry during and after the pandemic. Layered on top of this were mounting financial pressures and costly bets that exposed an overleveraged balance sheet that gave the business little margin for error. The story of WW is not one of just consumer preference change, but unpredictable, sudden shifts in the industry that left WW struggling to reinvent itself as a leading business in weight management. Pre-COVID Customer Segment Divergence and Financial Profile

Prior to the pandemic, the fixed-cost studio model that historically underpinned WW’s high-margin business was weakening as consumers were shifting away from WW’s core brand philosophy centered around in-person connectivity and best supported by the Workshops + Digital (premium) subscription offering. The % of premium subscribers tied to WW's legacy in-person studio business as a % of total subscribers declined from 42% in early Q1 2015 to 32% in Q1 2019. Figure 2 shows the continued divergence between the Digital (core) and Digital + Workshop (premium) subscribers. While the growth of the core segment masked the subscriber churn in the premium subscription tier, this was a problem because workshops provided sticker retention and higher engagement that led to higher LTV customers.

Figure 3: Subscriber composition: Core and Premium subscribers as a % of total subscribers

Additionally, the divergence between the two subscription tiers represented a story of deteriorating unit economics for the legacy business model because WW had to spend more on marketing to retain its increasingly core (digital-only) subscription base. This is indicated by the growth of marketing as a % of revenue from ~26% in 2015 to ~35% in 2019; meanwhile, revenue remained relatively flat throughout the period. In other words, WW was spending more to hold flat revenue, a clear indicator of structural headwinds. Therefore, diseconomies of scale from higher marketing costs reversed the trend in subscriber attrition was clear through WW’s declining EBITDA margins that fell from ~26% in 2015 to ~22% in 2019 [17]. Evidently, the company was not able to grow by aggressively pursuing marketing due to increased churn as capturing the same customer cohort became increasingly difficult.

Despite this adverse subscriber composition trend and declining margins, unlevered free cash flow remained positive leading into the COVID. However, the cracks in the business model were apparent as WW reported negative levered FCF in FY 2019 primarily due to its onerous annual interest expenses of ~$130mm. Although WW did not face large impending maturity walls in the near term, the excessive cash interest burdened FCF.

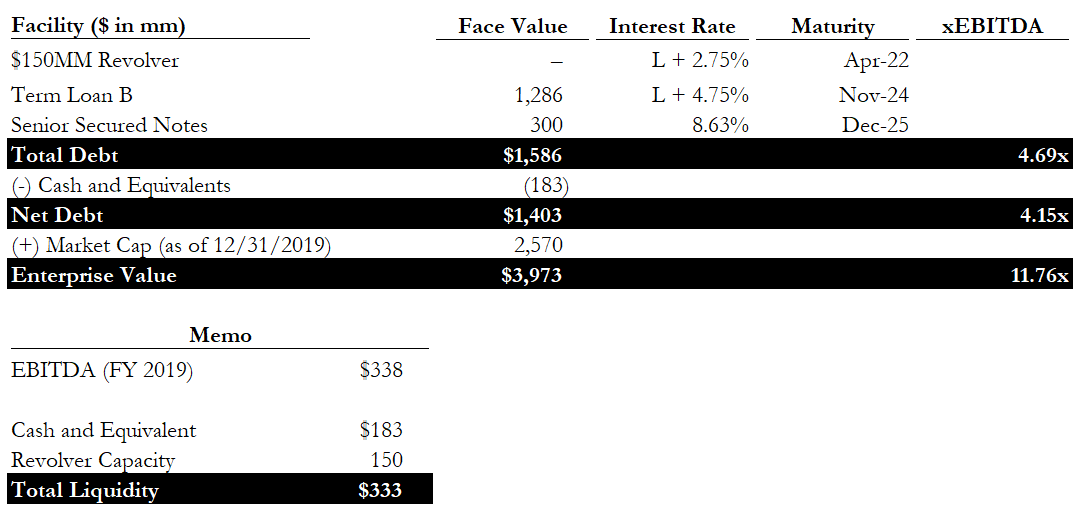

Figure 4: WW International Cap Table as of January 2020

COVID: Forced Digital Pivot

The COVID-mandated lockdowns permanently strained the company’s in-person studio subscription business and struck the member connectivity at its core. Premium Workshop + Digital subscribers fell ~43% Y/Y from 2019 to 2020 and forced the company to pivot towards enhanced virtual engagement for digital subscribers. More concerningly, despite the full reopening of the Company's studio locations in early 2021, premium subscription growth remained muted, and its subscription numbers never returned to pre-pandemic levels. As previously mentioned, WW had been gradually moving toward digital, but the pandemic made that transition immediate and non-negotiable.

Finally, a way to efficiently handle K1s and your taxes

Rx here,

I firmly believe that one of the most underrated benefits of working great buyside jobs is the ability to invest in funds that are usually reserved for Institutional Investors (often with backleverage and no fees, but that’s a discussion for another day).

The annoying downside? Getting K1s and seeing our tax filings get a lot more complicated. I have experienced this, and if you have not already, you will.

This is why, when Agent Tax reached out, I was so excited to learn more, and I am now excited to bring this service to you. Agent is a modern tax strategy firm purpose-built for investment professionals. You will receive a dedicated expert tax advisor (yes, human) who will leverage technology to proactively plan, prepare, and optimize your taxes.

Tax is everyone’s biggest expense, and this is a great service to minimize tax leakage. Click below to learn more with a free consultation and mention Pari Passu to get $100 off.

You are about to reach the midpoint of the report. This is where the story gets interesting.

Free readers miss out on the sections that explain:

• The Sequence Acquisition

• The Clinical Shortfall

• Why no out-of-court exchange or LME?

• Chapter 11 Filing

• Rough Justice Outcome

• Future Outlook

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive. Reach out for a group subscription.

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Full Access to Over 300,000 Words of Evergreen Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Access to the Restructuring Drive