Welcome to the 168th Pari Passu Newsletter,

With two bankruptcies in five years, each spanning multiple legal jurisdictions, McDermott represents one of the most complex corporate restructurings in recent memory. Once a major player in offshore oil and gas construction, the company’s acquisition of CB&I was meant to expand its capabilities but instead brought over significant liabilities and operational challenges.

This write-up explores McDermott’s dual restructuring journey, beginning with the financial and strategic missteps that led to its 2020 Chapter 11 filing, and continuing through its second, cross-border restructuring involving courts in the U.K., the Netherlands, and the U.S. We’ll examine key factors such as its business model, letter of credit obligations, the sale of Lummus Technology, and how creditor negotiations shaped each outcome.

But first, a great report from AlphaSense

As we announced last week, we’ve begun working with AlphaSense. Through this partnership, we encourage people to sign up for a free trial here.

With the free trial, you can explore the breadth of content available on the AlphaSense platform, including expert call transcripts, company documents such as earnings calls and filings, equity research, and industry and market reports—and leverage their generative AI capabilities to surface deep insights at a speed beyond what’s humanly possible.

In addition, today, you can download and read for free the Top Market Trends 2026 report, which distills signals from across its platform to help investors and operators spot the inflection points that will matter most.

In case you missed it last week, you can download here their report on how investment managers are using AI to accelerate research and the investment process to gain an edge.

McDermott Overview

Founding History

McDermott was founded in 1923 by Ralph Thomas McDermott as the J. Ray McDermott & Company to complete a contract to build fifty wooden oil rigs in Texas. Aided by the Texas oil boom of the early 1900s, the company grew rapidly and eventually expanded to Louisiana to capitalize on the growing offshore oil industry in the Gulf of Mexico. McDermott quickly became a pioneer in the offshore space, achieving milestones such as constructing the first offshore platform for 100ft of water in the Gulf and the first offshore platform in the Middle East. In 1954, McDermott went public and was listed on the NYSE in 1958. By the 1970s, McDermott had become a leading global provider of offshore engineering, procurement, construction and installation (EPCI) services [1] [3].

Business Model

So, what does an EPCI company even do? Simply put, McDermott constructs major infrastructure projects for major oil and gas exploration and production companies, such as ExxonMobil and Saudi Aramco. This includes offshore drilling rigs, transport pipelines, and storage facilities. Within the oil and gas industry, they function as a middleman, building the infrastructure for their customers to actually drill for resources, transport them, and refine those resources for sale [1] [6].

McDermott operates in a highly competitive, low margin industry. Approximately 92% of McDermott’s revenues come from the completion of construction contracts, which “are awarded on a competitively bid and negotiated basis” [1]. These contracts are principally fixed-price (accounting for 81% of total revenue), meaning that McDermott is paid a prearranged price for the completion of the project. Any cost overruns or other issues that arise during the project must be paid for by McDermott. This structure is advantageous for McDermott’s customers but is flawed for McDermott and its competitors – the combination of intense competition and fixed-price contracts creates scenarios where McDermott and its competitors bid contract prices down close to break-even. This is reflected by McDermott’s low-teens to single-digit gross margin, which we will examine later.

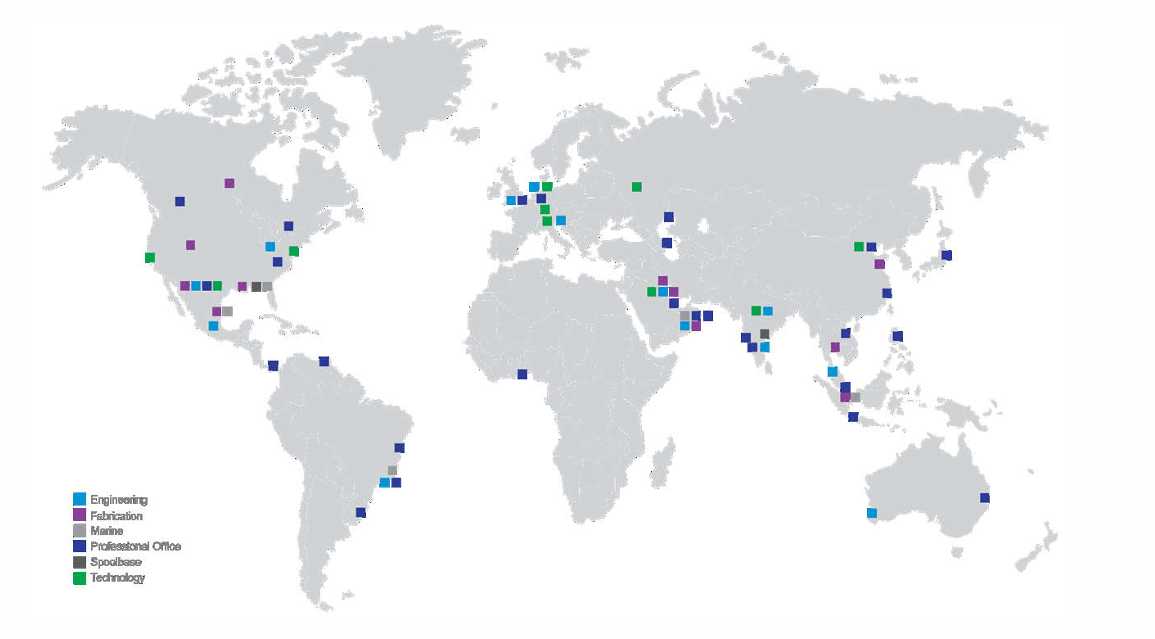

McDermott operates globally – and addresses four primary end markets [2]:

Offshore and subsea ($2.8bn, 34% of 2019 revenues): EPCI services for the upstream oil and gas sector across the full project life cycle.

Liquified natural gas ($1.4bn, 17% of 2019 revenues): Technology and EPCI services for liquified natural gas (LNG) facilities, which cool natural gas to a liquid state for efficient storage, transport, and international trade.

Downstream ($3.2bn, 38% of 2019 revenues): Construction of petrochemical and refinery units.

Power ($968mm, 11% of 2019 revenues): Construction of combined-cycle and simple-cycle gas power generation plants.

Figure 1: Map of McDermott’s operations [6]

Letters of Credit

Before we get into the details of McDermott’s restructuring, it’s important to grasp the role of its letter of credit (LC) facilities. McDermott constructs large-scale infrastructure projects for its clients, which take years to complete and hundreds of millions of dollars. Naturally, project sponsors want guarantees that their project will be completed in a timely manner, or compensation otherwise. As such, clients require performance guarantees in the form of LCs. These are issued by an administrative agent (usually a bank) on McDermott’s behalf to assure project sponsors that contractual obligations will be fulfilled, or compensation will be provided in case of a breach of contract or a default [1] [7] [13].

For example, imagine McDermott is building a subsea natural gas pipeline for Saudi Aramco under a $200mm contract. Within 30 days of being awarded the contract, McDermott must post a LC commitment through a pre-arranged LC facility with its administrative agent, say Barclays. Under this facility, Barclays is guaranteeing payment to Aramco if McDermott fails to meet certain obligations involving the pipeline project. The facility functions very much like a loan, with a predetermined principal amount and associated usage fees (similar to interest payments, but at lower rates). For instance, McDermott might have a $500mm LC facility provided by Barclays. The LC commitment amount typically equals approximately 5-10% of the total contract value. Let’s estimate 10% for our example, so McDermott posts a $20mm ($200mm * 10%) LC commitment under its LC facility with Barclays. The facility now has $480mm of outstanding LC capacity remaining.

At some point along the way, the project faces delays and misses a completion milestone. This constitutes a violation of the contract, and so Aramco may draw on the LC for compensation, and McDermott then has one business day to make the required payment to Aramco, equal to the posted LC commitment amount. If McDermott fails to make the payment, the lenders funding the LC facility are required to cover the shortfall. Note that Barclays is not solely responsible for making the LC payment, as LC facility commitments are typically syndicated out to multiple lenders. In return, these lenders receive secured debt claims in McDermott’s capital structure. As you can see, LCs function as a form of insurance for project sponsors in case something goes wrong and McDermott cannot pay [1] [7] [13].

Also, LCs have a funded and unfunded portion. When Aramco draws on the LC and the LC lenders pay on behalf of McDermott, the amount drawn becomes the funded portion of the facility – real cash has left the bank to satisfy McDermott’s obligation. Until that point, the LC was unfunded, meaning it existed only as a contingent guarantee. Once funded, McDermott owes that amount back to the LC lenders, and the liability shifts from off-balance-sheet to a secured debt obligation. From our example, the LC facility would have a funded portion of $20mm, an unfunded portion of $480mm, and the LC lenders would hold $20mm in secured claims against McDermott [15].

In terms of contract size, McDermott defines large contracts as those between $50mm and $250mm, although some contracts can range in the billions of dollars, such as a $3bn EPCI mega project that McDermott was awarded by Saudi Aramco in July 2019. These LCs must typically be posted within 30 days of the contract award. The average project duration ranges from two to four years, depending on the complexity and scope of work. McDermott spends a large portion of project costs early on, as each new project requires major front-end investment on engineering (designing the project), procurement (buying materials and equipment), fabrication (building major components in off-site facilities), and mobilization (transporting everything and preparing the job site). In contrast, payments from customers are usually tied to performance milestones and are often backloaded, with a portion retained until final completion [2] [36].

Events Leading Up to the 2020 Bankruptcy

Now that we’ve covered the key aspects of McDermott’s business model, we can turn to the events that triggered its first period of financial distress, which all started with an ill-fated acquisition.

CB&I Acquisition

In December 2017, McDermott ($1.9bn market cap) announced that it was acquiring onshore oil and gas EPCI company Chicago Bridge & Iron (CB&I, $1.7bn market cap) in a fully stock-funded deal in which CB&I shareholders received 0.82 shares of McDermott for each CB&I share that they owned. There was essentially no premium involved in the deal and valued CB&I at ~0.5x revenue (for context, McDermott was trading at ~2.2x revenue). The total enterprise value of the deal was ~$6bn [10] [21] [38].

By revenue, CB&I was much larger – $6.7bn in 2017 compared to McDermott’s $3.0bn. However, at the time, CB&I was struggling due to years of mismanagement. Back in 2013, CB&I paid roughly $3bn in a cash and debt deal to acquire The Shaw Group, a power generation construction company, which saddled it with Shaw’s problematic projects. Chief among these was Shaw’s subsidiary Stone & Webster, which had contracts to build two new nuclear power plants that suffered huge delays and cost overruns. CB&I ultimately sold its stake in the subsidiary to partner Westinghouse for $161mm, recording a $973mm loss on net assets sold, to free itself from liability of certain delayed projects. In March 2013, CB&I purchased Phillips 66’s coal technology business (which specialized in turning coal into a cleaner-burning gas used for power and chemical production), which turned out to be a poorly timed bet on the rapidly declining coal industry due to cheaper fossil fuel alternatives and new environmental regulations. These untimely expansion moves, combined with the fact that many of CB&I’s legacy projects were facing cost overruns, left CB&I overextended and financially vulnerable. From 2015 to 2017, CB&I’s revenue declined by 37%, its gross margin from 12.7% to 0.1%, and its EBITDA margin from 6% to (3%). By the end of 2017, CB&I’s stock had fallen by 44% and its one-year default risk spiked to an all-time high of 7.85% [10] [16] [17] [18].

McDermott saw the acquisition as an opportunity to consolidate with a larger, but struggling, competitor at a low price, who they believed was at the tail end of its struggles. In doing so, McDermott nearly tripled its revenues, from $3.0bn in 2017 to $8.4bn in 2019, and aimed to establish a vertically integrated onshore-offshore EPCI company that provided infrastructure across the oil and gas lifecycle, from exploration and transport (McDermott) to refinement and chemical treatment (CB&I).

Cost Overruns and Liquidity Issues

In reality, McDermott could not be more wrong – instead of a mounting gradual recovery, CB&I continued to deteriorate, and McDermott was left holding the bag on its portfolio of troubled contracts. In 2019, two legacy CB&I projects, the Cameron LNG export terminal and the Freeport LNG export terminal, ran a total of $318mm above the agreed upon contract value (for context, 2019 revenue was $8.4bn). With some of McDermott’s own projects facing issues, the company recorded a total of $689mm in cost overruns in 2019. From an accounting perspective, these overruns represent the total amount that actual project costs exceeded the estimated costs, which translated directly to gross losses [1] [2].

Figure 2: McDermott’s Project Cost Overruns in 2019 [2]

At the same time, McDermott was winning a lot of new contracts very quickly. For context, the company had a record-high project backlog of $19bn at the end of 2019, compared to a backlog of $3.9bn at the end of 2017. These contracts added to the company’s near-term financial obligations because each new project requires major front-end investment (as we explained earlier) and substantial LC commitments and working capital requirements, while cash flows are typically only realized near the end of the project lifecycle. In total, McDermott would need approximately $1bn to $2bn in LC availability to support its project backlog. The mismatch between project expenditures and collections underscores the importance of adequate LC capacity and liquidity for McDermott’s operations, making it a key factor in how new financing and the bankruptcy plan would eventually be structured [1] [2] [8].

Prepetition Financials

To provide context, let’s take a look at McDermott’s financials since the acquisition took place.

Figure 3: McDermott’s Financials from 2014 to 2019 [2] [8] [9]

As a reminder, the 2018 revenue figure includes the half year impact of the CB&I acquisition, and 2019 the full year impact. Immediately, we can see a similar trend across McDermott’s gross, EBITDA, and adjusted EBITDA margins – each reached a high point in 2017, and then deteriorated in the following two years. As we discussed earlier, by 2017, CB&I was already a loss-making machine, barely breaking even at the gross margin level. Its unprofitable operations dragged down McDermott’s margins in 2018, and the continued decline in 2019 can primarily be attributed to the $689mm in cost overruns [2] [20] [21].

Additionally, notice that McDermott’s leverage ratio was only 1.3x in 2017, before jumping to 17.6x in 2018 due to a combination of lower EBITDA and higher debt. This is because McDermott entered into its main secured credit agreement in 2018, which included an undrawn revolving credit facility (RCF) and a $2.26bn TL that was primarily used to repay certain indebtedness of CB&I, fully repay $500mm of its second-lien notes, and fund operations and working capital needs. The added interest expense from the additional borrowings significantly weighed down on McDermott’s annual cash flow generation, beginning in 2018 [2].

In 2019, since adjusted EBITDA was negative, we can use 2018’s adjusted EBITDA margin of 3%, which is a rough estimate of McDermott’s margin post-CB&I acquisition, albeit under distressed circumstances. With these adjustments, 2019 leverage was 20x (5,107 / (8,431 * 3%)), illustrating that leverage worsened even under flat margin assumptions. In reality, margins declined further, meaning actual leverage was even higher [2] [14] [19].

We can also estimate how much runway McDermott had at the end of 2019. In Q3 2019, McDermott reported $677mm in unrestricted cash and $5mm in revolver availability, for $682mm of total liquidity. The company burned ~$351mm of cash in Q4 (for a total of $755mm in the year), leaving ~$331mm in liquidity. Using an average estimated cash burn of $189 million per quarter ($755mm / 4), McDermott had less than two quarters of runway remaining. This estimate likely understates the urgency, as the company’s cash burn was accelerating due to declining profitability.

Prepetition Initiatives

Superpriority Credit Agreement

In early September 2019, having identified that it was facing an acute liquidity crisis and was at risk of breaching several debt covenants, McDermott retained Evercore and AlixPartners to address liquidity and develop a revamped business plan. This was not received well by the public – shares plunged by 62% and market cap fell from $1.1bn to $420mm. With market sentiment souring, the company’s initial attempts to raise liquidity via 1) issuing new debt that ranked junior to existing secured debt and 2) sale of its “Tank” (sold for $475mm in 2024) and Pipe Fabrication assets were unsuccessful. Further stretching vendor payables, which grew from $595mm at the end of 2018 to $1.4bn by Q3 2019, was also no longer an option [1] [14].

Days later, McDermott announced that it was planning to sell its “Tech” asset, which refers to its 50% stake in the joint venture Lummus Technology, the process technology business that it acquired from CB&I. McDermott stated that it had received an unsolicited bid for its stake for over $2.5bn, and shares promptly recovered 50% [1].

However, McDermott and its advisors needed more time and financing to 1) consummate a value- maximizing sale of Lummus and 2) deleverage its overburdened capital structure, and 3) obtain additional liquidity and LC availability to continue operations and address its $19bn order backlog. McDermott’s secured lenders came to the rescue – in October 2019, McDermott announced a new $1.7bn Superpriority Senior Secured Credit Facility, with immediate access to $550mm in new money via a TL facility and the capacity to issue up to $100mm in new LCs. There were three additional tranches of funding that could be accessed if certain conditions were met, which will come into play later. The Superpriority Facility was designed to potentially transition into a debtor-in-possession (DIP) facility in the case of an in-court process [1].

With $550mm in new money, McDermott began developing a revamped business plan. The new plan narrowed McDermott’s focus to areas where it had the most experience and strongest performance. This included offshore oil and gas projects in the Middle East, where McDermott already had in-house construction yards and long-term client relationships; select subsea projects that offered higher margins; LNG projects with lower overall construction risk; petrochemical facilities that McDermott could help design from the early planning stages; and its long-standing business building large storage tanks [1].

McDermott and its advisors also began contemplating an out-of-court restructuring. However, despite the new money from the Superpriority Facility, the necessary balance sheet deleveraging was deemed impossible to achieve out-of-court because it would require the virtual unanimous consent of various creditors and shareholders. Negotiations for achieving that level of consent would likely take months, and the new money from the Superpriority Facility did not provide sufficient runway to complete those negotiations. Additionally, there was no guarantee that negotiations between so many stakeholders (secured lenders, bondholders, vendors, customers) would even be successful, so given the urgency of McDermott’s business deterioration, focus shifted to an in-court process [1].

$69mm Bond Interest Payment

On November 1st, 2019, McDermott skipped out on a $69mm interest payment on its Senior Notes, and elected to enter a 30-day grace period. Before the grace period expired, McDermott entered into a forbearance agreement, which is an arrangement that temporarily delays enforcement of debt obligations, with an ad hoc group of ~35% of the Senior Notes [1] [6].

On December 1st, 2019, McDermott gained access to Tranche B under the Superpriority Facility, which consisted of an incremental $250mm TL and an additional $100mm in LC availability. With access to Tranche B, McDermott and its advisors concluded that it had approximately six weeks left to reach an agreement before it ran out of liquidity. At this point, it was decided that the Lummus sale would be consummated via a section 363 sale as part of a Chapter 11 process, which would produce more value, as opposed to a rushed out-of-court sale process. Alarmingly, many of McDermott’s vendors were getting increasingly impatient, given that they were not getting paid, and began seizing vessels, asserting liens on collateral, and filing collection lawsuits. The race was now not only against liquidity, but also against McDermott’s vendors. In early January, the Lummus prepetition marketing process successfully secured a binding stalking horse bid from a joint partnership between The Chatterjee Group (a private investment firm with interests in energy and technology) and Rhône Capital (a $11bn AUM global private equity firm), for $2.7bn. Finally, with continued support from its customer base, McDermott was able to successfully draft a restructuring support agreement (RSA) [1].

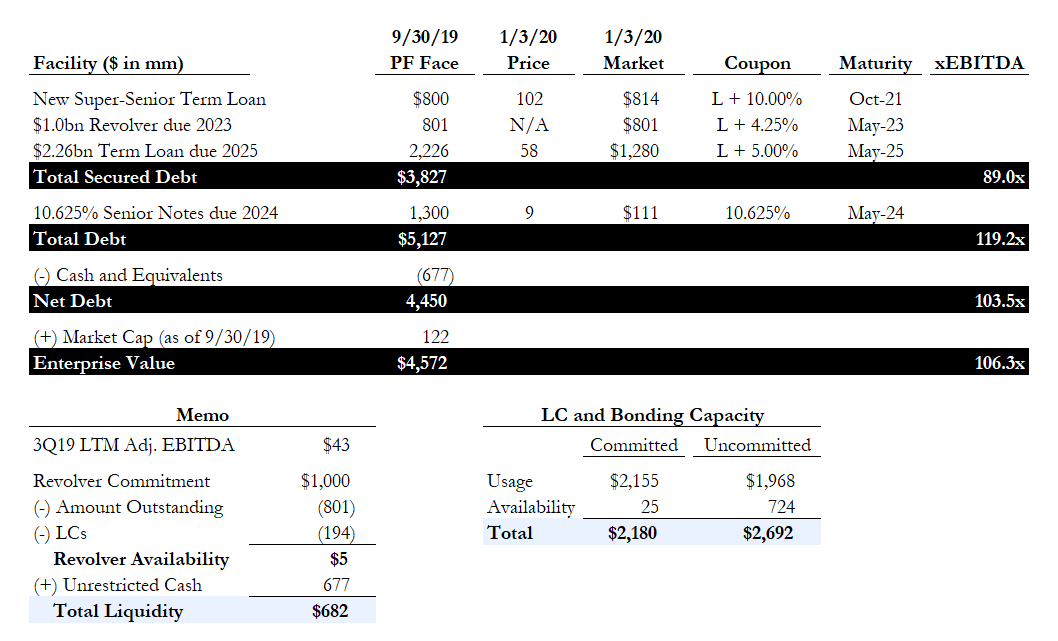

Prepetition Capital Structure

Figure 4: McDermott’s Q3 2019 Capitalization Table [19]

McDermott had $5.127bn of total debt going into its Chapter 11 filing. The LC and Bonding Capacity table displays McDermott’s total LC availability, which by Q3 2019, was only $25mm under its committed facilities. In other words, the company could only post LC commitments of up to $25mm under its TL LC agreement and standalone LC Facilities. The company also had ~$2.7bn in total uncommitted agreements, which function similarly to committed LCs, but the issuer has discretion to decline an LC request, so availability is more difficult to access if an issuer fears it will not be fully repaid, such as when a company is distressed [2].

2020 Chapter 11

Restructuring Support Agreement

On January 21, 2020, McDermott filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the Southern District of Texas with a RSA supported by a majority of its creditors across its capital structure. The key terms of the RSA are explained below [1].

DIP Financing

McDermott secured a $2.8bn DIP financing package from its existing secured lenders, the same ones who backed the earlier Superpriority Facility. The package included a new $1.2bn secured TL and $543mm in LC availability, while also rolling up the $800mm TL and $200mm of LCs that were issued under the Superpriority Facility, meaning those earlier amounts were folded into the new DIP facility and given the same senior status as the new money. Put another way, the package consisted of a $2.1bn TL ($1.2bn new + $800mm roll-up) and $743mm in LC availability ($543mm new + $200mm roll-up). The DIP facility TL would later be repaid using proceeds from the tech business sale and a make-whole exit TL (for the amount not covered by the tech sale proceeds), while the LC facility would be carried over, dollar for dollar, into the post-bankruptcy Super Senior Exit Facility [6].

Senior Secured Claims

McDermott’s secured lenders agreed to equitize over $3bn in funded debt in exchange for 94% of company’s post-reorg equity and $500mm in take-back senior secured TLs. The exchanged debt consisted of the $801mm of funded borrowings under the $1.0bn Revolver, the $2.2bn TL, and $2.2bn in funded portions of the prepetition LC facilities. As such, recovery through take-back debt was ~10% [1].

Lummus Technology Sale

One of the most important components of the RSA was the sale of the Lummus Technology business. The business was ultimately sold to the stalking horse bidders for $2.7bn, as no competing bids were made. The proceeds of the sale would applied in the following waterfall [6] [37]:

To fund a minimum cash balance of $820mm required by the business plan in order to support the debtor’s go-forward business

To repay the $1.2bn new money TL under the DIP facility

Payment of the outstanding amounts under the $800mm Superpriority TL that was rolled-up by the DIP facility

To fund cash to support new or additional LC availability

Repayment of the prepetition secured claims on a pro rata basis

The proceeds of the sale primarily went towards the first two uses, with some residual value trickling down to repaying the rolled-up $800mm Superpriority TL.

Unsecured Creditors

Holders of the Senior Notes received 6% of the post-reorg equity, certain warrants, and the right to participate in a $150mm equity rights offering. The GUCs, which included vendor claims and executory contracts, passed through unimpaired to allow McDermott to continue fulfilling its project obligations without interruption [1] [6] [19].

Exit from Chapter 11

Summary Capitalization

On June 30th, 2020, in just under six months, McDermott exited Chapter 11, thanks to a streamlined prepackaged Chapter 11 process. The company emerged with $500mm in take-back debt and $2.1bn in LC availability, plus the rolled-over prepetition LC facilities. Below is a progression of its capitalization. Leverage is based on projected 2020 adjusted EBITDA of $521mm [12] [19]:

Figure 5: McDermott’s Post-Chapter 11 Summary Capitalization [19]

You are about to reach the interesting part of the report.

Free readers miss out on the sections that explain:

• Events Leading up to the Second Bankruptcy

• Prepetition Initiatives

• Prepetition Capital Structure

• Sanctioning the Plans

• Final Thoughts

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive.

Unlock the Full Analysis and Proprietary Insights

A Pari Passu Premium subscription provides unrestricted access to this report and our comprehensive library of institutional-grade research

Upgrade NowA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Full Access to Our Entire Archive

- 150+ Reports of Evergreen Research

- Full Access to All New Research

- Access to the Restructuring Drive

- Join Thousands of Professional Readers