Welcome to the 161st Pari Passu newsletter.

In today’s edition, we’re diving into Intrum, a Swedish debt collection giant that, over the past century, has grown from a small credit information provider to Europe’s largest credit management firm. Intrum grew rapidly through a series of large-scale M&A and loan portfolio acquisitions, while its capital structure grew increasingly large and complex. After years of operating with elevated leverage, post-COVID European fiscal policy eventually caught up with Intrum.

What followed was one of the most interesting cross-border restructurings in recent memory. In late 2024, Intrum, headquartered in Sweden and operating entirely within European borders, filed a prepackaged Chapter 11 in the Southern District of Texas, sparking intense litigation and drawing a dividing line between domestic and foreign noteholders.

This writeup breaks down Intrum’s history, business model, and the aggressive merger that brought the company to where it is today. We’ll also break down the series of events stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing out-of-court negotiations among opposing creditor groups. We’ll end by covering what ultimately drove Intrum into the Texas courts, how the company emerged following a remarkably smooth restructuring transaction, all the way to the three tender offers in the fall.

Before we get started, I would like to say thank you for all the support over these three years. This week, Pari Passu was mentioned twice in the Altice co-op litigation against Apollo. I honestly never thought we would get here so quickly, and I have also never been more optimistic about our future.

In addition, we sent out an email on Tuesday with some important updates on our publication and future writeups (you can find it in your inbox by searching “PP”). Make sure to read it to take advantage of our crazy BF offer.

The private equity back office is on the brink of a transformation, and AI is leading the charge

By 2030, operational precision, automation, and real-time insights won’t be a “nice to have”, they’ll be the baseline. In this tech-forward environment, firms that still rely on outdated manual workflows or clunky third-party administrators risk falling behind. Firms that embrace AI will scale faster, reduce errors, and unlock powerful new operational and investment intelligence.

Read Carta's free report to learn:

- The three models of back-office operations, and why hybrid tech-service platforms are the new gold standard

- How AI is quietly revolutionizing fund reporting and more

- What agentic AI means for eliminating repetitive tasks, and how it becomes your team’s smartest “co-pilot”

- AI’s emerging role in diligence, LPA analysis, and even deal sourcing

Intrum History

Intrum, headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden, is Europe’s largest debt collector. The company’s roots trace back to the 1920s, when both European and American consumers and businesses started using credit for an increasing number of purchases. As credit’s popularity increased, more and more businesses bore the repayment risk of credit purchases, eventually impacting financing efforts, among other challenges.

In 1923, Sven Göransson capitalized on this opportunity, founding Justitias Upplynsnigbryå, a firm with two functions: debt collection and credit information. By the late 1930s, he had sold off the credit information arm to focus exclusively on debt collection, rebranding to Justitia. Following World War II, as the postwar economic recovery fueled an explosion in consumer credit, the need for debt collection services continued to rise [1].

In the 1970s, Göransson sold the business down to his son Bo at a time when the company was struggling, with just 30 employees. Bo, however, pushed for expansion into new markets and offerings. In 1971, the company first entered international territory via a licensing agreement in Switzerland. Justitia also acquired a number of Swedish debt collection competitors throughout the same time period. Lastly, the company also expanded into accounts receivable management, collecting receivables on behalf of clients, sometimes even before delinquency [1].

By the 1990s, the company, now Intrum Justitia, had established a footprint across Northern and Western Europe. The acquisition of UK-based CAS Group in the early 1990s also gave Intrum a strong presence in London, while post-Cold War liberalization opened doors in Eastern Europe. By 2003, the company operated in 21 countries and generated Swedish Krona (SEK) of 2.7bn or $270mm [1]. Note that for the rest of this writeup, we will report SEK in USD, using a flat exchange rate of 10 to 1.

In the early 2000s, Intrum began consolidating its collection operations from autonomous geographical units to a shared operating model, allowing for more efficient collections and consistent practices. The company also expanded into a massive growth engine: portfolio investing (PI). Instead of servicing loans on behalf of banks, Intrum began purchasing the defaulted loan portfolios itself (at a steep discount) and making collections itself. In the next section, we’ll dive in-depth into the economics of PI. While PI transferred credit risk to Intrum, it also presented an opportunity for significant upside.

In 2017, Intrum Justitia merged with one of its largest rivals, Norwegian firm Lindorff. This merger created Europe’s largest credit management services provider. Today, over 100 years from inception, Intrum remains Europe’s largest credit management firm, present in over 20 countries with thousands of employees and hundreds of institutional clients [1].

Figure 1: Intrum’s Debt Collection Markets [1]

Business Model Overview

To understand how Intrum got to where it is today, it’s important to understand its two business models. Intrum operates a hybrid credit management model that combines portfolio investing and servicing.

Portfolio Investing (30% of revenue):

In portfolio investing, the asset-heavy side of the business, Intrum acquires non-performing loan portfolios (NPLs) from banks and financial institutions, often at steep discounts of roughly 20-30 cents on the dollar [2]. NPLs are loans for which the borrower is no longer making scheduled principal or interest payments. In most regulatory contexts, a loan is classified as non-performing when it is 90 days or more past due.

Under IFRS (the international version of generally accepted accounting principles), these NPLs are added to Intrum’s balance sheet at fair value. In this context, fair value represents the present value of Expected Remaining Collections (ERC), adjusted for the expected cost to collect. For example, assume Intrum purchases $100 in face value of loans. If it expects to collect $75 over the next three years, $75 would be the reported ERC. If collection costs are $5 per year, totalling $15, total net collections would equal $60. To determine the balance sheet fair value, Intrum would discount these projected cash flows, totalling $60, using a predetermined discount rate, to account for the time value of money and other risks of collection. For illustrative purposes, if Intrum used a discount rate of 10%, it would report the loan at a $49.7 fair value on its balance sheet.

In other words, this means portfolio investments are reported on the balance sheet at a discount to their face value. Additionally, Intrum reports gross remaining collections as ERC over a loan’s lifetime. In 2024, Intrum reported $2.5bn in book portfolio investments but $5.3bn in ERC, representing a more than 50% discount, accounting for both collection costs and the time to collect [2].

Once the NPLs are acquired, Intrum collects via a mix of soft outreach (calls, texts, etc.), structured repayment plans, and legal enforcement where permissible. While collections begin immediately, recovery curves are typically longer term, with a significant share of recoveries arriving 3-10 years post-acquisition. The upfront capital outlay, paired with the long payback horizon, amplifies the credit risk of the NPLs.

Intrum generates profit via the spread between collection inflows and the portfolio acquisition cost, net of operating and funding expenses. When Intrum purchases a distressed loan at 25 cents on the dollar, for example, it does so with the expectation that long-term recoveries will exceed this purchase price, potentially collecting 2-3x its initial investment over a decade. As expected, profitability is heavily dependent on accurate collection forecasts and cost-efficient collections.

Additionally, a third, and very important, variable in portfolio investing is leverage. Intrum doesn’t just purchase NPLs using cash from operations; it uses a combination of revolving credit facilities, term loans, and secured or unsecured notes. To illustrate how Intrum earns a return, we’ll use a brief example of portfolio acquisition economics.

Assume Intrum purchases a $100mm NPL Portfolio at 25 cents on the dollar, equating to a purchase price of $25mm. Intrum reasonably expects to collect 40% of these loans’ face value over the 10 years, meaning it determines Expected Remaining Collections (ERC) of $50mm. Assuming collections are evenly distributed across this timeline, that equates to cash collections of $5mm per year. Additionally, assume that Intrum funds 60% of this purchase with debt and the remaining 40% with balance sheet cash, equating to $15mm of debt. Also, assume that the debt carries a fixed 7% interest rate and that the company has a 20% collection cost.

Figure 2: Levered vs. Unlevered Portfolio Acquisition

The image above depicts this scenario, along with another example in which no debt is used. Critically, the levered scenario generates a 2.3x MOIC / 11.4% IRR while the unlevered only generates a 1.6x MOIC and 9.6% return. While these scenarios featured quite conservative cash-collection estimates (common for NPLs), they highlight the benefits of leverage in generating a viable return. The levered acquisition’s 11.4% IRR closely mirrors Intrum’s 2024 reported adjusted portfolio return of 12% [2].

Servicing (70% of revenue):

In contrast to the capital-intensive nature of portfolio investing, servicing represents the asset-light side of Intrum’s business model. Rather than purchasing loans outright, Intrum acts as a third-party collections agent for banks, utilities, telecom companies, and other creditors. These clients retain ownership of the underlying receivables while Intrum is contracted to manage and recover unpaid balances, typically in exchange for a performance-based fee tied to collections.

Intrum applies many of the same recovery methods as it does in its portfolio business, including outbound communications, installment plan structuring, and legal action, but without the direct credit exposure or upfront investment. This makes servicing lower-risk and more predictable, but lower-margin, compared to owning portfolios outright.

Servicing contracts can range from early-stage pre-delinquency monitoring to late-stage recoveries, including court-enforced collections. Some are “forward-flow” arrangements, in which new receivables are added continuously, while others are static pools. Servicing also plays a strategic role in Intrum’s business model, helping build relationships with financial institutions that often become sources of future portfolio investment opportunities. While less capital-intensive, servicing contributes meaningfully to recurring revenue and operating profit.

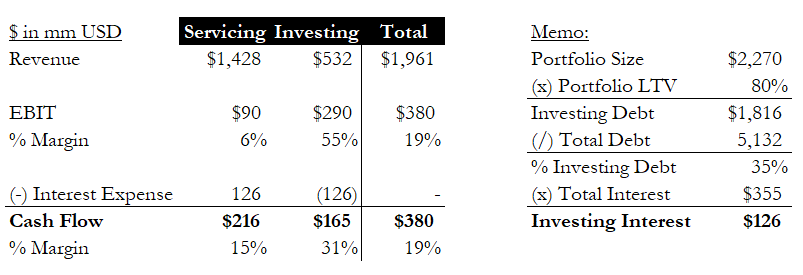

Servicing, alongside portfolio investing, enables Intrum to offer a broad credit management solution. For context, as of 2024, investing accounted for $532mm (30%) of total revenue while servicing accounted for $1.42bn (70%). In terms of EBIT, which is management’s only breakout of segment profitability, Investing generated $290mm while servicing generated $90mm. These represent 55% and 6% margins, respectively, a substantial difference between segments. However, reported EBIT distorts segment profitability because it ignores the interest expense associated with leveraged acquisitions, as all interest is deducted as a servicing expense. In reality, a substantial portion of Intrum’s interest expense is associated with the debt from the levered portfolio acquisitions. Therefore, we’ve restated reported EBIT to account for Intrum’s estimated portfolio-associated interest, based on the company’s current portfolio size, making an assumption on the portfolio LTV in order to estimate how much debt (and interest) should be categorized as a cost in the Investing segment.

Figure 3: Interest-Adjusted Restated EBIT

The image above provides a more accurate picture of segment profitability and presents a different story from what management reports in Intrum’s 2024 financials. After accounting for the interest on portfolio-related debt, Investing’s profitability is materially lower than reported. This perspective will remain important as we move through Intrum’s story.

The Lindorff Merger

Now that we’ve reviewed Intrum’s business model, let’s return to the company’s story, picking back up in the 2010s. Following its rebranding as Intrum Justitia, the company entered an aggressive growth phase via both organic growth and acquisitions.

Figure 4: Intrum’s Lindorff-Era Financials [3]

Between 2016 and 2019, revenues nearly tripled from $587mm in 2015 to $1.6bn in 2019. Adjusted EBITDA also climbed from $367mm to $1.07bn over the same period. Most of this growth was not organic and was instead attributable to Intrum’s merger with Lindorff. Impressively, throughout this expansion period, Intrum was able to hold margins flat. This expansion, which included over $1.5bn of portfolio acquisitions, came at a cost, as net debt rose from $726mm in 2016 to nearly $5bn in 2019 [3].

As we mentioned above, the most pivotal expansion was the 2017 merger with Lindorff, which created Europe’s largest credit management company. At the time, Intrum was a public company, valued at $2bn, trading on Nasdaq Stockholm, and Lindorff was privately held, backed by private equity firm Nordic Capital. In the transaction, Lindorff received newly issued INTRUM shares, representing 47% of the pro forma entity, valuing Lindorff equity at $1.85bn, in exchange for 100% of Lindorff’s equity [4]. Following the deal, Nordic Capital became the largest shareholder in Intrum, which remained public. Critically, the deal also featured the assumption of Lindorff’s substantial debt load as a PE-backed company (Intrum assumed roughly $2.2bn of net debt as a part of the merger). This is reflected in the large jump in net debt from 2016 to 2017. While the Lindorff merger doubled Intrum’s revenue and nearly doubled adjusted EBITDA, the increase was not enough to outpace the new debt load, and net leverage increased from 2x to 5.9x [3]. Eventually, as the new entity began to realize the cost synergies that drove the transaction (management projected $80mm annually) [4], EBITDA margins improved, and net leverage gradually decreased, hovering around 4.5x over the next two years.

Another important note on this four-year period is the impact of low borrowing costs on Intrum’s business model. During this period, the European Central Bank’s main refinancing rate sat at 0.00%, where it had remained since early 2016 [6]. This ultra-low rate environment helped fuel two major tailwinds for Intrum. The first was the cheap funding of portfolios. Since Intrum could finance more NPL purchases at lower interest rates, it could capitalize on the spread between cash collections and debt service.

The second effect stems from the broader availability of consumer credit. As low rates drove greater demand for consumer loans, over time, more of these became non-performing, expanding Intrum’s addressable market. Both of these effects are illustrated in Intrum’s purchasing of over $1.5bn of NPLs in the period between 2017 and 2019.

COVID-19 (2019 to 2022):

Figure 5: Intrum’s COVID-Era Financials [3]

The next major point in Intrum’s story was the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing macroeconomic impact on the company’s financials. While the pandemic spurred substantial global economic uncertainty, Intrum weathered the shock with relative stability. While top-line growth slowed to the mid-single digits due to COVID-related dampening of collection efforts, Intrum’s business model was quite resilient relative to many other industries. Impressively, the company held EBITDA margins steady, reflecting strong cost control measures and the underlying resilience of its collection infrastructure.

Importantly, unlike in the United States, Europe did not see a sharp rise in consumer borrowing post-COVID. The ECB’s refinancing rate had already been at 0.00% since 2016, meaning there was no new wave of rate cuts to stimulate new borrowing. Notably, however, Intrum paused nearly all new NPL portfolio acquisitions during 2020 and 2021. This was very likely due to macroeconomic uncertainty surrounding COVID, the resulting difficulty in properly pricing NPL portfolios, and the need to preserve liquidity. Still, as COVID-related uncertainty subsided, low rates allowed Intrum to continue funding portfolio acquisitions for much of 2022.

Driving Distress - Post-COVID Inflation & Rate Hikes

Figure 6: Intrum’s Distressed Period Financials

Beginning in late 2021, inflation surged across Europe due to post-pandemic supply chain issues, energy price spikes, and geopolitical tensions. For reference, we’ll examine the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP), which can essentially be thought of as the European equivalent of the US’s Consumer Price Index (CPI). From October 2020 to October 2022, the YoY change in HICP rose from -0.3% to 10.6% [5]. These rising prices placed greater pressure on European consumers, especially those with limited financial cushions. For Intrum, this translated into weaker collections, as consumers were forced to prioritize essential expenses over debt repayments. This effect was very clear in 2023 and 2024, as Intrum’s adjusted EBITDA fell to 52%, resulting in a decrease of over $400mm. Beyond EBITDA, these weaker collections hit the balance sheet in the form of impairments to Intrum’s NPL portfolio, which, as a reminder, is calculated based on the present value of estimated future collections. As collection efforts weaken, Intrum projects fewer net collections, translating to a lower total ERC. Additionally, as interest rates rise, so does Intrum’s discount rate, lowering the balance sheet fair value. In 2022 alone, the company recorded a portfolio impairment of $577mm, followed by $12.4mm in 2023 and $132mm in 2024 [2]. Notably, this impairment, like all others, is added back to Intrum’s adjusted EBITDA. Therefore, the drop in EBITDA you see above stems from operational deterioration, not balance sheet impairments.

The second impact of European inflation was on the ECB's fiscal policy. To combat inflation, the ECB began an aggressive sequence of rate hikes, the first in over a decade. In mid-2022, the ECB lifted its refinancing rate from 0.00% to 2.50% by year's end, and continued to raise rates to a peak of 4.50% by September 2023 [6]. For a business like Intrum, which relies heavily on debt to fund portfolio acquisitions, this was a significant headwind, as increased interest costs directly reduced the profit spread the company could earn on its collections, while not providing additional benefits on the collections side.

To examine the aforementioned factors’ effect on Intrum’s liquidity position, we must first select an appropriate metric that serves as a proxy for cash flow. Both IFRS EBITDA and Intrum’s adjusted EBITDA are imperfect measures. IFRS EBITDA includes the impact of non-cash portfolio impairments, while Intrum’s adjusted EBITDA adds back restructuring and acquisition charges, which, for Intrum, were quite recurring cash expenses. Therefore, to best calculate Intrum’s cash burn, we’ll start with IFRS EBITDA and add back the large portfolio impairments to find the best proxy for operating cash flow.

Figure 7: Estimated Cash Burn [2], [3]

The table above effectively illustrates the impact of the factors listed above on Intrum’s liquidity. First, as the ECB hiked rates, interest expense rose from $180mm to $300mm+ for the following three years [3]. This, paired with sustained debt-funded portfolio acquisitions and the $400mm drop in EBITDA, resulted in nearly $1bn in cumulative cash burn from 2022 to 2024. As a result, Intrum began to burn through its liquidity, which it had consistently held above $1bn in previous years. By 2024, Intrum had drawn down its entire revolving credit facility, and liquidity sat at just $250mm.

One point to note is that despite a material improvement in 2024 cash burn, Intrum still burned through $524mm of liquidity, of which only $104mm can be attributed to cash burn. The remaining $400mm can be traced back to the paydown of nearly $900mm of debt in 2024. In mid-2024, Intrum was facing the July maturity of its 2024 Eurobonds (we’ll dive into the full capital structure soon), along with other 2024 maturities. Intrum was unable to refinance out of these maturities and had not yet negotiated a restructuring solution. Instead, Intrum was forced to sell a portfolio of NPLs to Cerberus Capital, using the $720mm of proceeds entirely to pay down debt. We can infer that the remaining hit to liquidity was largely attributable to the paydown in debt in excess of NPL sale proceeds.

Additionally, in 2025 and 2026 alone, Intrum had $3.5bn in upcoming debt maturities that were increasingly difficult to refinance [7].

Intrum’s Capital Structure

Before we get into Intrum’s controversial restructuring, it’s important to review the company’s capital structure.

You are about to reach the midpoint of the report. This is where the story gets interesting, and we dive into the restructuring details.

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive. Take advantage of our Black Friday offer and get $200 off/year in perpetuity.

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Full Access to Over 300,000 Words of Evergreen Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Access to the Restructuring Drive