Welcome to the 143rd Pari Passu newsletter.

In one of our most-read articles, we explored the case of Spirit Airlines and the company’s proposed triple dip strategy. Spirit, like the company we will be exploring today, is also a low-cost carrier airline. Since the pandemic, several other airlines have fallen into a similar path of bankruptcy – including Azul, another Latin American airline that just filed for Chapter 11 as well.

While many airline bankruptcies are driven primarily by shifting consumer preferences, our case study today on GOL Airlines explores the operational disruptions beyond the company’s control that led to its ultimate downfall. From the grounding of a crucial segment of its fleet to a brutal combination of pandemic-induced demand collapse and fx volatility, GOL presents a different, and arguably more complicated, narrative for us to explore.

AMC’s LME scorecard — 9fin unpacks one of the market's most complex LMEs

AMC Entertainment has closed another chapter in its complex liability management saga, settling with a litigious group of 7.5% first lien noteholders who were previously left out of a major 2024 debt deal.

This new deal grants them improved security and new notes, while rewarding early-consenting term loan holders and the Wachtell-led convert group with outsized gains. Meanwhile, holdouts and uninvolved creditors see reduced recoveries or none at all. This analysis outlines the winners and losers of the deal, highlighting how litigation pressure and strategic timing influenced outcomes. Retail shareholders continue to be heavily diluted, having funded much of the debt maneuvering.

9fin’s team unpacks the legal nuance, capital structure shifts, and deal dynamics — backed by exclusive buyside sourcing — to decode one of the market’s most complex LMEs.

Airline Industry Overview

The global airline industry operates on thin margins and high fixed costs, with the average profit per passenger globally reaching only $7. This industry exists within a uniquely technical and capital-intensive framework shaped by cyclical demand and high regulatory restrictions. Volatile costs such as fuel and recurring costs like aircraft maintenance expenses, especially as the global fleet of planes grows older, consume large portions of revenue [2]. Intense competition driven by cost-conscious passengers also makes maintaining a sustainable margin exceedingly difficult.

The airline sector is comprised of a variety of business models. Below are a few examples of passenger (non-cargo) carriers [3]:

Full-service network carriers (FSNC) serve all passenger market segments and often carry cargo as well. These models use hub-and-spoke networks, a flight routing system where traffic flows through a central airport (hub) that connects multiple destinations (spokes). Examples include Emirates and Singapore Airlines, which place a higher priority on network breadth and service quality rather than offering lower fares.

Low-cost carriers (LCC) target price-sensitive passengers and utilize point-to-point networks, another type of routing system that connects destinations directly without requiring transfers through a central hub. Examples include Southwest and JetBlue Airways, which, as the name of this category suggests, focus on low prices as the main differentiating feature. Ultra low-cost carriers (ULCC), like Frontier and Spirit Airlines, operate the same business model as LCCs but target the most price-conscious passengers; ULCCs drive prices even lower than LCCs.

Regional carriers primarily operate short-haul flights between smaller cities and major hubs, often under capacity purchase agreements (CPAs) with larger network airlines. This means that regional carriers fly on behalf of their major airline partners with smaller aircraft and lower seat counts, utilizing the major airline’s branding and flight codes. An example is Eurowings, which operates under Lufthansa.

Given their operational efficiency and appeal to price-sensitive travelers, LCCs in particular have become more popular in global aviation, particularly in emerging markets [3]. Their simplified model offers a stark contrast to traditional FSNCs and plays a central role in shaping competitive dynamics, especially in regions like Latin America. Unlike FSNCs that often operate a mix of wide-body and narrow-body aircraft, LCCs usually standardize their fleets around a single aircraft family, such as the Boeing 737 or Airbus, since narrow-body aircraft are easier to maintain. By operating fleets of one or two types of planes, LCCs can lower training costs for pilots and crews, simplify inventory management for spare parts, and increase efficiency for maintenance. As a result, LCCs routinely achieve daily aircraft utilization rates exceeding twelve block hours, compared to roughly eight hours for FSNCs. Block hours are a standard industry measure that represents the total time from when an aircraft leaves the gate at departure to when it arrives at the gate upon landing. Higher block hour utilization indicates more efficient use of aircraft, which helps spread fixed costs over more revenue-generating flights and supports the low-cost structure that defines the LCC model.

As we briefly mentioned above, LCCs also rely on point-to-point routing systems. Compared to the hub-and-spoke model for FSNCs, this network design reduces the complexity of scheduling and minimizes turnaround times between flights. The point-to-point system also requires fewer ground personnel. All of this contributes to higher cost savings for LCCs, with the tradeoff being fewer route combinations and limited service to smaller markets [4].

GOL: Brazil’s First LCC

Founded in 2000, GOL Linhas Aéreas Inteligentes SA (GOL) was the first LCC Brazilian airline after its founder, Constantino de Oliveira Junior, introduced the business model to the country. GOL was largely responsible for the tripling of Brazil’s domestic air travel market, which tripled from 30mm passengers in 2001 to nearly 100mm in 2019 [1]; for context, the US domestic air travel market comprised around 800mm passengers in 2019, up from 600mm in 2001 [26] [27]. GOL rapidly captured over one-third of Brazil’s domestic airline market, following closely behind LATAM Brasil and Azul, and has since grown into one of the largest LCCs both in South America and internationally. By the end of 2024, GOL’s network spanned over sixty domestic routes and thirteen destinations in nine foreign countries [1].

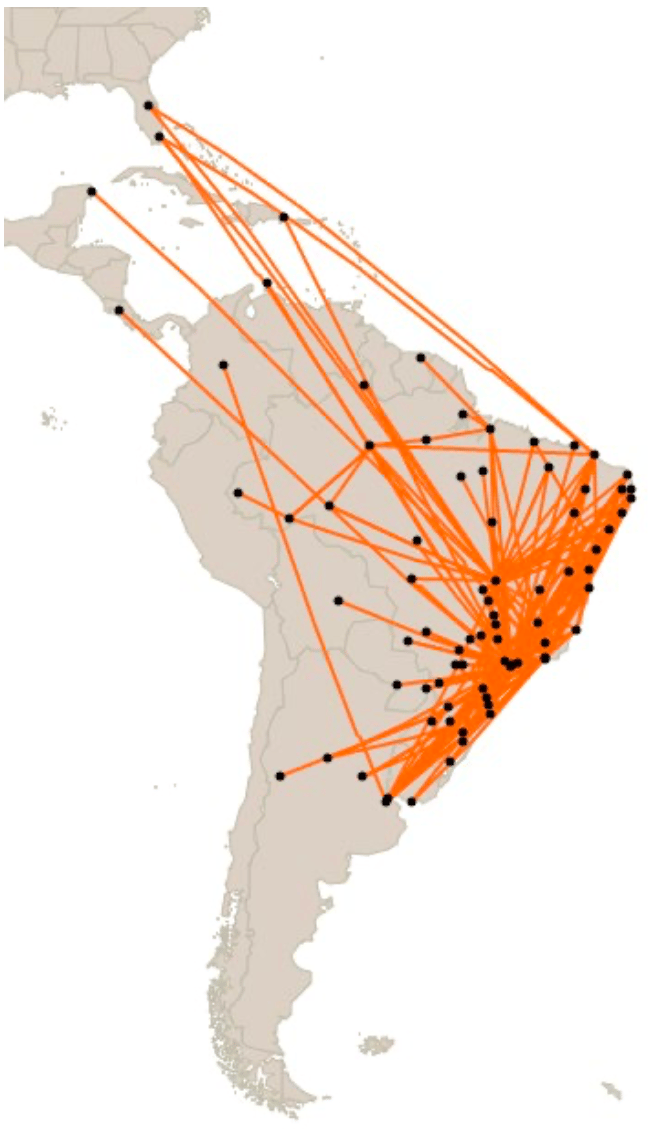

Figure 1: GOL’s Flight Route as of December 2024 [1]

Below is GOL’s corporate structure. GOL functions as a holding company that controls a network of nine subsidiaries, both domestic and offshore. Its key Brazilian subsidiaries include GLA, the airline’s main operating arm responsible for flight operations; Smiles Fidelidade, which runs GOL’s loyalty program; and GTX S.A., a holding company. Other Brazil-based entities like Smiles Viagens e Turismo S.A. and its affiliate Smiles Viajes y Turismo S.A. serve as travel agencies. GOL also operates through a number of offshore subsidiaries, including GAC Inc. (Cayman Islands), GOL Finance (Luxembourg), and GOL Finance Inc. (Cayman Islands), which are primarily used for international financing. Smiles Fidelidade Argentina S.A. and Smiles Viajes y Turismo S.A. (Argentina) are international counterparts of GOL’s loyalty and travel businesses. Additionally, GOL Equity Finance (GEF), a Dutch foundation-owned SPV which will become relevant later, issues certain convertible bonds [14].

Figure 2: GOL’s Corporate Structure [5]

GOL operates an all-Boeing 737 fleet with an average of over eleven block hours per day (meaning each plane is flying, on average, for more than eleven hours daily), which is among the highest utilization rates in the global airline industry. GOL’s high utilization allows the company to spread its fixed costs across more revenue-generating flight hours; the more an aircraft flies, the lower the cost per flight or per passenger becomes. This also helps GOL keep its load factor, the percentage of seats occupied by paying passengers divided by total seat capacity, in the mid 80% range [5].

In 2019, the year before distress, GOL was generating around $2.4bn in annual revenue, $600mm gross profit (25% gross margin), $390mm operating income (16% operating margin), and free cash flow of $270mm in 2019 [9]. Net margin has historically been low, with the company only flipping a positive net income after 2016 [7]. The reason why we do not use EBITDA as a metric to assess financial performance here is that it excludes the effect of aircraft lease expenses, a significant operating expense that, when ignored, overstates profitability. In 2019, GOL’s market cap was around $14bn [6], and the company operated a fleet of around 140 Boeing 737 airplanes [9].

GOL’s core financial performance is supported by two operating segments: flight transportation and loyalty program. The flight transportation segment is made of passenger and cargo revenue, and the company’s overall revenue is driven primarily by its passenger sales. Prior to 2021, GOL’s passenger sales made up around 97% of total revenue; the remaining 3% came from cargo and other sources [11]. Though cargo did not historically, and still does not, make up a significant portion of the company’s revenue, it’s still worth noting that GOL's cargo arm, GOLLOG, is Brazil’s largest air cargo provider. In 2023, GOLLOG led the domestic cargo market with a 36% market share by volume. Revenues from cargo nearly doubled from 2022 to 2023 and continued to rise throughout 2024, accounting for around 7% of GOL’s total revenue by the end of 2024 [1]

In addition to passenger and cargo revenue, GOL recently added a third revenue stream: Smiles, GOL’s GOL’s loyalty program. Smiles was originally a separate publicly-listed entity and was not consolidated into GOL’s core financials until 2021. By the end of 2021, Smiles was generating $150mm in revenue, accounting for just over 10% of total revenues [11]. Bookings made using Smiles rewards accounted for around 20% of total ticket sales by the end of 2024. However, while Smiles made up a larger portion of revenue since its integration into GOL’s core business, passenger revenues continued to make up 90% of total revenue through 2023 [1].

International Grounding of Boeing 737 MAX 8

A downside of the LCC model is that its profitability depends heavily on high aircraft utilization and limited revenue. Recall from our summary of passenger carrier types that LCCs are reliant on high volumes of passenger ticket sales and short-haul operations due to the low cost of fares; LCCs cannot charge high prices, so their success depends on the volume of sales. This means that while FSNCs can rely on cargo services and international routes to cushion demand shocks, LCCs are more susceptible to periods of volatility because they have fewer avenues for profitability.

When LCCs experience financial struggles, these challenges typically stem from some sort of consumer preference change. For example, Spirit’s lack of customer service deterred travelers from choosing it over other low-cost airlines; consumers’ preference for a better experience played a significant role in Spirit’s downfall.

However, in GOL’s case, the company’s initial challenges were not rooted in consumer preferences. Instead, disruptions to GOL’s fundamental tools of business – its airplanes – were the catalyst for the company’s financial distress.

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

Upgrade NowA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Get Access to the Restructuring Drive

- Join Thousands of Readers

- Lock your price into perpetuity