Welcome to the 172nd Pari Passu newsletter.

In today’s edition, we are switching gears from the typical LME deep-dives to a more topical technical primer, focusing on breaking down cooperation agreements (also known as co-ops). We begin by exploring the growing use of co-ops, and the key drivers behind this development in the restructuring landscape. However, unlike typical coverage on co-ops, the focus is not simply on explaining their growing use, but also on understanding the growing opposition from borrowers and sponsors against these agreements. We have already covered the motivations and trade-offs that lenders face when deciding whether to join a co-op, in our past write-up on co-ops, so make sure to check it out. In case you missed it, it was used as a source in the Altice lawsuit, so definitely a read worth your time.

For this write-up, we have synthesized technical analysis of credit documentation with the unfolding antitrust litigation currently reshaping the restructuring landscape. We will begin by defining the core legal mechanics of a co-op and the specific restrictive covenants that bind lenders to a unified front. Following this, we explore the landmark Selecta case to deconstruct how cooperation agreements can be used to engineer aggressive liability management exercises and minimize borrower optionality. Then, we dive into the Altice USA (Optimum) lawsuit, analyzing the first major instance of a debtor leveraging the Sherman Act to characterize a lender bloc as an illegal cartel. The cases are followed by an exploration of the benefits of co-ops and their value-add in the restructuring process. Finally, the piece examines the market’s counter-response, specifically the emergence of "anti-cooperation" clauses designed to neutralize these pacts before they can be formed. This post is not intended to be a deep-dive of the Selecta and Altice USA transactions, but simply focuses on the respective co-op litigation for these cases (see previous coverage on Selecta).

Applied AI: Tracking Trends Across Earnings Season

Earnings season delivers a data-driven view of companies, industries, and the broader economy. Using AlphaSense’s Deep Research and Generative Grid, we aggregate recent earnings and conference call transcripts to show how companies in diverse industries are deploying AI across business functions.

Technical Overview

Origins: From Defense to Offense

Before delving into the technical aspects of a co-op, it is crucial to trace the origins of this development in the restructuring landscape. The rise of co-ops is a direct response to the era of "lender-on-lender violence," which became a defining trend of the credit markets following years of post-pandemic covenant-light lending. Sponsors began exploiting such loose creditor documentation to execute novel transactions (such as an uptier in Serta Simmons or a dropdown in J Crew). To protect themselves from such transactions, creditors began banding together through co-ops. Over time, however, co-ops have evolved from a defensive hedge used by creditors to an aggressive sword used to take control of transactions, like the Selecta case that we will explore below.

At its core, a co-op is a binding agreement between a group of creditors designed to restrict individual creditor negotiations with the borrower and limit creditor-on-creditor violence [1]. The two most important elements of the co-op are the individual creditor negotiations blocker and the steering committee (also known as a SteerCo, which this will be explained in greater detail later) governance framework [2].

The first overarching aspect pertains to individual prohibitions. This is perhaps the most powerful element of the co-op and puts restrictions on individual members from negotiating with the debtor independently to craft a beneficial outcome for itself while harming other creditors. This is accomplished through three interconnected mechanisms. The first is the ‘no shop’ clause: this provision prevents any individual member of the creditor group from entertaining or soliciting private restructuring offers from the borrower, ensuring the debtor cannot negotiate on a piecemeal basis. Second, this is done through the ‘exclusive dealing’ mandate, which requires that all negotiations with the borrower occur solely through the group’s appointed representatives, which is usually a small group of SteerCo creditors. The last and third aspect is the ‘exit lock’. To maintain the group's voting power, this mechanic prohibits members from selling their debt unless the buyer agrees to be bound by the same cooperation terms, effectively "locking in" the bloc. This dynamic has the following key effect: it makes exiting the position significantly harder, so it is likely that the creditor holds the position for a relatively long time horizon [2].

The second overarching silo of the co-op deals with voting thresholds and governance principles for the SteerCo. This goal is achieved via three different elements. First, it is done through binding supermajorities for transaction or amendment. This framework requires a high percentage of the group's total principal (typically 66.7% or higher of dollar amount of credit owned) to approve any deal. Secondly, it is accomplished through required lender syncing. By aligning the co-op’s internal approval threshold with the voting requirements of the underlying credit agreement (the indenture), the group guarantees it can unilaterally control or block any major amendment or waiver [2]. In other words, by matching the co-op thresholds to those of the original indentures, the group ensures that if they reach a consensus internally, they automatically have the exact power needed to control the legal outcome of the actual indenture. Lastly, the co-op allows for sacred rights amendments. This allows the majority group to collectively lower the consent thresholds for fundamental loan terms, principal amount, and maturity date. Lowering the consent thresholds for sacred rights within a cooperation agreement ensures that the majority group maintains absolute, ongoing flexibility to rewrite fundamental payment terms without interference from minority holdouts. The Selecta restructuring, which we will later explore in depth, is the premier example of this dynamic in action. Additionally, most co-ops have a fixed expiration date (typically around 6-12 months) to prevent the group from being permanently locked into a pact [3].

To summarize, the co-op architecture roughly focuses on two key silos: blocking individual creditor negotiations with the borrower, and outlining a playbook for the SteerCo to drive a potential transaction. In essence, the co-op transforms individual creditors into a unified negotiating block that channels all decision-making through a SteerCo, effectively replacing competitive dynamics with coordinated strategy.

The Prisoners’ Dilemma: Why Creditors Join

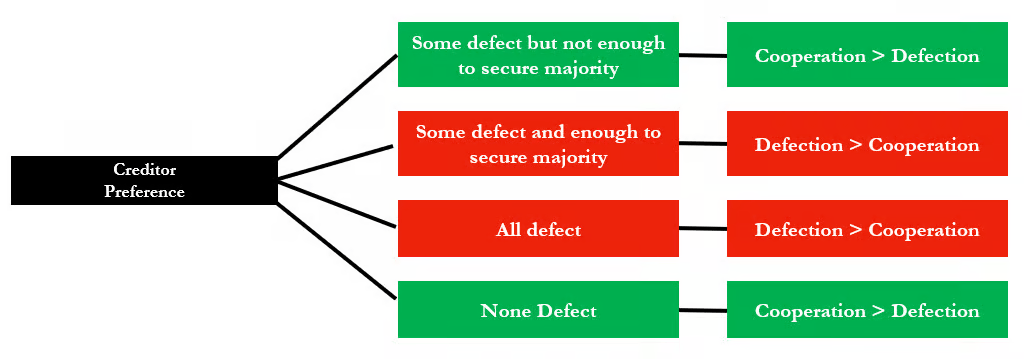

Lastly, for a distressed creditor, the decision to join a co-op is not a preference, but a calculated response to a high-stakes prisoner’s dilemma (see image below). The choice boils down to a fear of being left out of a major out-of-court transaction, effectively wiping your recovery value. As shown in the image below, the preference for cooperation or defection is dictated by the resulting voting power. Cooperation is the optimal strategy when none or some creditors defect, but not enough to form a majority. Any lender remaining in the minority who refused to join finds themselves orphaned in a junior position with significantly less recovery value. On the other hand, if enough creditors defect to form a majority and cut a successful side deal, defecting is more lucrative than cooperating. This represents the opportunity cost of joining a co-op: the risk of giving up a potentially lucrative opportunity to be the lucky defector who cuts a private, superior deal with the company [1]. At a fundamental level, this is the calculus that many creditors now face when deciding whether to join a co-op. By joining, a creditor is able to limit its downside at the cost of giving up a potentially lucrative opportunity.

Figure 1: Co-ops presented through the lens of the prisoner’s dilemma

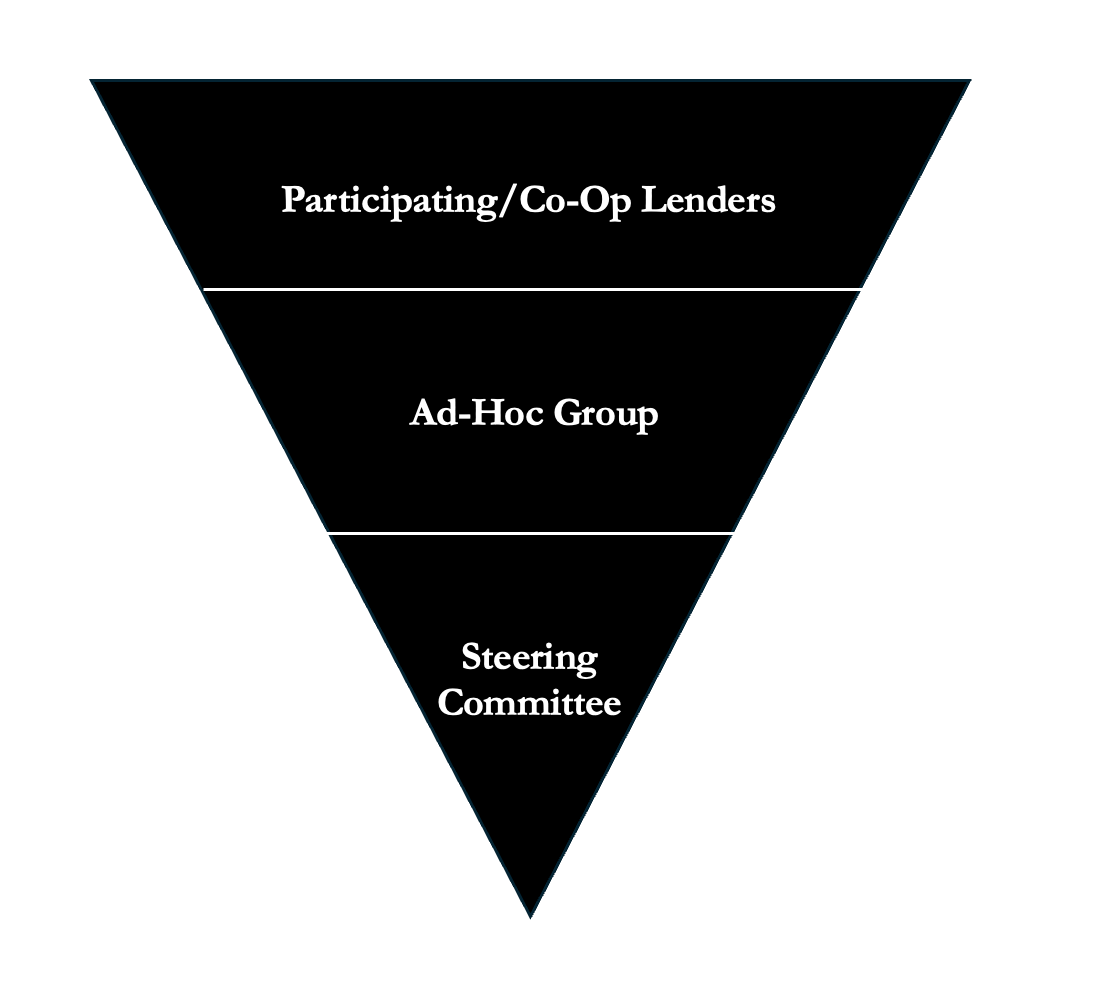

There are various stakeholders involved in the process of a co-op. Of course, from a high-level, there are the participating, non-participating lenders and the sponsor/borrower. It is prudent to further break down and understand the various stakeholders to understand the inherent dynamics at play. First, participating lenders refers to the broad group of creditors who have signed the co-op. Then, within this group, there exists the AHG, which is the specific group of lenders that drive negotiations with the borrower and ‘initiate’ the co-op. Within the AHG exists the SteerCo, which consists of some AHG creditors who handle day-to-day tactical decisions and interfaces directly with professional advisors. To summarize, we start with the participating lenders who sign the co-op, of which some make up the AHG, of which some make up the SteerCo (the figure below captures this relationship).

Figure 2: Understanding the hierarchy of creditor coordination

Co-Op Design Intuition

Now that we have explored the fundamental structure of a co-op and the stakeholders at play, it is worth understanding the intuition behind these agreements. Market participants should essentially view the co-op as an optimization problem, where the goal is to minimize creditor-on-creditor violence while maximizing possible recoveries. Fundamentally, the only way to do so is by prohibiting individual creditor negotiations with the borrower, minimizing the possibility for a side deal. With that in mind, first co-ops only become effective once a minimum of 50% of the relevant creditor base has joined. This is rather intuitive as most transactions require a 50%+1 majority for approval, so without adequate support in the group, the co-op fails to serve as a blocker. Second, to solve for our optimization focus of minimizing lender-on-lender violence, a co-op must include a central covenant that prevents members from entering into side-deals with the borrower. The agreement often includes "sharing clauses" which mandate that if any member does receive a private payment or superior recovery, that value must be redistributed pro-rata among all co-op members. By viewing co-ops through this optimization lens, where we have two key constraints, we can better understand their purpose and role in driving a cohesive creditor strategy.

Co-Op Limitations

So far, we have explored the fundamental underpinnings of a co-op. Based on the discussion above, many may think that this is a flawless solution to problems in the world of restructuring. However, co-ops come with a host of issues and drawbacks that must also be given equal attention and weight. First, and perhaps most importantly, is the case where there is a complex capital structure and groups of creditors that have multiple holdings across the capital stack. A co-op is a global mandate, meaning that upon signing, a creditor is committing its entire exposure across the capital stack. Here, creditor A cannot enter into a co-op for the 1L position while excluding its unsecured holding exposure from the pact. The reason for grouping creditor exposure as ‘net exposure’ is to prevent conflicted creditors from utilizing the co-op as a shield while simultaneously pursuing private side-deals for their junior or unsecured positions. A co-op is inflexible, applying a one-size-fits-all solution to all problems, which becomes critical when creditors have conflicting interests [2].

To better understand how clashing interests are not compatible with co-ops, it is logical to walk through a specific scenario. Let us consider the following example: the capital structure for Company A consists of $100mm in 1L notes due 2030, $100mm in 2L notes due 2030, and $25mm in unsecured notes due 2027, followed by $50mm of preferred shares, and finally $25mm of equity. In addition, creditor A has a position in both 1L notes and the unsecured notes. The last piece of the puzzle is that the company is struggling financially, with the company’s liquidity likely to be depleted by the 2030 maturity wall. Now, here is the tricky dilemma facing creditor A:…

You are about to reach the midpoint of the report. This is where the story gets interesting.

Free readers miss out on the sections that explain:

• Selecta Case

• Understanding the Minority Creditors’ Challenge

• Breaking Down Selecta Litigation

• Jumping into the Judge’s Shoes: Ruling on Selecta?

• Why is the Selecta LME Different?

• Comparing Selecta to the Altice USA Co-Op Litigation

• The Future: Anti-Cooperation Clauses

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive.

Unlock the Full Analysis and Proprietary Insights

A Pari Passu Premium subscription provides unrestricted access to this report and our comprehensive library of institutional-grade research

Upgrade NowA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Full Access to Our Entire Archive

- 150+ Reports of Evergreen Research

- Full Access to All New Research

- Access to the Restructuring Drive

- Join Thousands of Professional Readers