Welcome to the 173rd Pari Passu newsletter.

In today’s edition, we examine Franchise Group, a retail-heavy roll-up that marketed itself as a franchisor but operated in many respects like a levered brick-and-mortar retailer. At its peak, the company owned nationally recognized brands such as The Vitamin Shoppe and Pet Supplies Plus, built through an expansive debt-funded acquisition strategy.

As this write-up explores, the franchise model that appeared asset-light on paper masked the company’s significant exposure to struggling brick-and-mortar categories and operating risk from its high concentration of company-owned stores. Franchise Group’s eventual take-private transaction further complicated matters by introducing a HoldCo–OpCo corporate structure that shaped creditor recoveries in bankruptcy. The resulting Chapter 11 became one of the most contentious cases of 2025, driven by a group of structurally subordinated lenders who wielded aggressive litigation to extract holdup value despite being deeply out of the money.

Note: the Tuesday editions, like this one, are available to everyone. If you are looking to access our full premium research (see the full archive here), you can do so here.

GPT-6 expected Q1 2026. What Will New Launch Mean For Finance?

December’s GPT 5.2 launch brought significant improvements to the LLMs. Analysts, associates, and C-Suites are wondering how close to a true “AI analyst” will we come to in 2026.

Endex, OpenAI’s Excel agent, is already capable of generalist work such as building DCFs, comps, and sensitivity analysis.

Investment banks and PE firms are racing to bring AI agents into their workflows, as they prepare for future LLM breakthroughs.

To request access to Endex, click here.

Company Overview

Franchise Group (“FRG”) was a privately held, U.S.-based operator of franchisor businesses. The company traces its roots back to Liberty Tax, a publicly traded provider of tax preparation services founded in 1997 that operated with a franchise business model. In August 2018, Vintage Capital Management, an investment fund founded by Brian Kahn, acquired shares of Liberty, becoming its majority shareholder. The following year, in August, Kahn merged Liberty with Buddy’s Home Furnishings, a rent-to-own furniture retailer that operated with a very different business model but also employed a franchisor model. Following the acquisition of Buddy’s, Kahn shifted Liberty’s long-term strategy towards acquiring other franchise-oriented businesses. In the process, Liberty’s name was changed to Franchise Group [1].

In the years following the acquisition of Buddy’s, FRG pursued an active M&A strategy focused on acquiring franchisor businesses. Notable transactions during this period included the acquisitions of The Vitamin Shoppe and Sylvan Learning, among others [1].

Figure 1: Timeline of FRG’s M&A activity [1]

Business Model

FRG functioned as a multi-brand operator that owned and controlled several consumer businesses, each with its own management team and operating platform. While day-to-day operations were handled at the brand level, financing, capital allocation, and strategic decisions were coordinated centrally. The portfolio used a mixed structure of franchised and company-operated stores, generating earnings from direct retail operations as well as recurring franchise fees [2].

FRG offered both single-store and multi-store franchise programs. Under both types of agreements, franchisees were responsible for all upfront investment costs, including purchasing/leasing the land, building, equipment, inventory, and other supplies. In exchange, franchisees paid FRG an initial franchise fee when opening a store, as well as additional fees upon the renewal or transfer of the franchise agreement. During ongoing operations, franchisees paid FRG recurring monthly royalties calculated as a percentage of store-level sales. This structure allowed FRG to earn relatively stable, recurring revenue while being less directly exposed to the risk and volatility involved with store-level operations [2].

In contrast, company-operated locations were owned and run directly by FRG. In these stores, FRG was responsible for all operating and capital costs, including rent, labor, inventory procurement, marketing, and maintenance. Revenues from these locations flowed directly to FRG, but so did all of the operating risks [2].

Brand Portfolio

Figure 2: FRG’s operating businesses

At the end of 2022, FRG operated over 3,000 retail locations across six businesses, with nearly 54% of those locations being franchised. Each of these businesses operated a franchise model, but otherwise shared few other similarities.

The Vitamin Shoppe: The Vitamin Shoppe is a specialty retailer focused on nutritional products such as vitamins, supplements, and natural wellness items. In 2022, the company operated over 700 locations, primarily company-owned, and generated $1.2bn in revenue [2]. FRG acquired The Vitamin Shoppe in December 2019 for $6.50 cash per share, valuing the company at $208mm. The purchase implied a roughly 3.2x multiple of 2018 adjusted EBITDA [3]. To help fund the acquisition, FRG raised a new $70mm senior secured term loan and drew $70mm from its ABL revolver [4].

Pet Supplies Plus: Pet Supplies Plus (“PSP”) is a leading pet supplies retailer and franchisor. Most locations also provide grooming, pet-wash, and related services via its Wag N’ Wash subsidiary. In 2022, the company operated nearly 700 locations and generated $1.3bn in revenue [2]. FRG acquired PSP in January 2021 in an all-cash deal valued at $700mm, implying an 8.7x multiple of 2020 adjusted EBITDA. FRG raised $1.3bn in new term loans to help fund the acquisition [5].

American Freight: American Freight is a value-focused retailer offering furniture, home accessories, and appliances through in-store and online channels. In February 2020, FRG merged American Freight with Sears Hometown and Outlet Stores, creating a one-stop destination for home furnishings. In 2022, it operated 371 locations, generating $883mm in revenue [2]. FRG acquired American Freight in December 2019 in an all-cash transaction valued at $450mm, fully funded by a new $700mm credit facility [6].

Buddy’s Home Furnishings: Buddy’s Home Furnishings is a specialty retailer offering furniture, appliances, and household items through rent-to-own agreements that provide customers with flexible access without long-term commitments. As of 2022, the company operated over 300 locations and generated $57mm in revenue [2]. FRG acquired Buddy’s in August 2019 for $12 cash per share in a $122mm deal [7].

Badcock Home Furniture: Badcock Home Furniture is a regional home furnishings retailer located primarily in the southeastern U.S. In 2022, the business operated close to 400 locations, primarily franchised, generating $919mm in revenue. FRG acquired Badcock in November 2021 in an all-cash transaction valued at $580mm, funded with $575mm in new term loans [2].

Sylvan Learning: Sylvan Learning is an education services franchisor providing supplemental tutoring and test preparation programs for K-12 students. In 2022, the business operated over 550 franchised locations and generated $42mm in revenue. FRG acquired Sylvan Learning in October 2021 for approximately $83mm, positioning Sylvan as one of the more asset-light businesses within FRG’s portfolio [2].

Taken together, FRG’s operating structure varied greatly across its portfolio, ranging from true franchisors such as Buddy’s and Sylvan Learning to more classic retailers such as The Vitamin Shoppe and American Freight. The table below summarizes FRG’s business portfolio as of 2022.

Figure 3: A breakdown of FRG’s businesses

Events Leading up to Distress

Brick-and-Mortar Retail Headwinds

FRG’s operating environment was shaped by broader secular and cyclical pressures facing the retail industry. Over the past two decades, the U.S. retail sector has undergone a structural shift toward e-commerce, with consumers progressively favoring online channels over physical stores. While U.S. brick-and-mortar retail sales grew at around 5-6% from 2010 to 2018, e-commerce expanded substantially faster at around 12-15%, doubling its share of total retail sales to roughly 10% by 2018. This divergence left many physical retailers facing lower foot traffic and limited pricing power, particularly in categories with low differentiation [8] [9]. The pandemic exacerbated these pressures, temporarily shutting stores, disrupting supply chains, and accelerating the shift toward online purchasing, further weakening performance across FRG’s portfolio of retail brands with primarily brick-and-mortar footprints.

These headwinds were later compounded by a tightening macroeconomic environment beginning in 2022, when high inflation, which peaked at 9.1% in June 2022, prompted the Federal Reserve to raise rates from near zero in March 2022 to 5.25-5.50% in mid-2023, causing SOFR to rise from roughly 0.05% to over 5.30%, materially increasing floating-rate borrowing costs. As a company with floating rate debt, FRG was directly exposed to this shift, reducing financial flexibility and liquidity at a time when operating performance was already under pressure.

Additionally, much of FRG’s revenue “growth” had been achieved via debt-fueled M&A, with organic growth remaining largely stagnant since 2020. However, given FRG’s roll-up-esque model, organic growth is not always the best measure of success. In some cases, taking on debt to fund growth can be effective if the company is able to achieve meaningful cost synergies, which should be reflected by higher margins. Instead, FRG’s gross and EBITDA margins have steadily decreased since 2020, indicating a decline in operational efficiency. From 2020 to 2022, EBITDA increased from $238mm to $377mm while debt more than doubled, from $574mm to nearly $1.4bn. As a result, leverage grew by over 50% to 3.7x in 2022 from 2.4x in 2020, as increases in total debt outpaced growth in underlying earnings power.

While cash flow actually grew from 2020 to 2022, issues began to emerge when we examine FRG’s 1H 2023 financials (last publicly reported financials before the company was taken private, more on this later), with cash flow falling to just $19mm. In particular, the steady decline in FRG’s interest coverage ratio highlighted how the company’s strategy caused interest expense to grow faster than operating cash flow, signaling that the leverage was becoming unsustainable and the cost of growth was exceeding the actual growth.

Figure 4: Prepetition financials [2]

Signs of Weakness Emerge

FRG’s profitability began to weaken significantly beginning in late 2022 and through 2023 as macroeconomic conditions shifted against parts of its portfolio. Consumers were beginning to feel the real effects of higher inflation and rising interest rates by the latter half of 2022, which constrained discretionary spending and reduced housing-related demand, weighing on categories such as furniture and appliances. This disproportionately affected American Freight and Badcock, which operated in highly competitive markets with largely undifferentiated products.

American Freight, in particular, began to experience performance pressure beginning in late 2022. Adjusted EBITDA declined to ($19.6mm) in 2H 2022 from $37mm in the prior-year period. The deterioration was driven by the aforementioned weaker demand for large discretionary spending due to high inflation, which remained above 7% for most of 2022, compounded by the expiration of COVID-era government stimulus programs that had previously supported spending [2].

Figure 5: American Freight 2H 2021/2022 financials [2]

As for Badcock, while full-year results for 2021 are not available because it was acquired in late 2021, it undoubtedly faced similar pressures as American Freight, given their similar operating models. Specifically, Badcock sold higher-priced furniture and appliances to a lower- and middle-income customer base that relied heavily on customer financing. In the higher-rate environment, fewer customers qualified for financing, borrowing costs increased, leading to weaker payment performance, higher delinquencies, and lower overall profitability [2].

Figure 6: 1H 2022/2023 segment financials [2]

American Freight and Badcock continued to face challenges into 2023, with operating results firmly in the red. Across 1H 2023, American Freight reported adjusted EBITDA of ($24mm) and a net loss of ($121mm). The company operated in a highly competitive, low-margin industry with a predominantly brick-and-mortar retail model, factors that, together with limited brand strength, made it difficult to justify a valuation anywhere near the $450mm paid at acquisition in 2019. Similarly, adjusted EBITDA at Badcock in 1H 2023 fell by nearly (89%) year-over-year, and the $580mm all-cash deal in late 2021 to acquire the company was looking like another overpay. Notably, FRG financed that transaction through $575mm of new term loans, putting incremental cash flow pressure on the company from the additional interest expenses.

In theory, a franchisor model should partially insulate the parent company from the impact of these underperforming businesses. However, in practice, this insulation did not materialize at FRG. Of the 371 American Freight locations, only 9 were franchised, leaving FRG to bear the full operating risk of this loss-making, cash-burning business. Consequently, American Freight's margins were inconsistent with a true franchisor model and instead reflected those of an undifferentiated retailer. More broadly, despite marketing itself as a franchised business operator, nearly 50% of FRG’s locations were company-owned, causing it to function more like a capital-intensive retailer than an asset-light franchisor. The limited use of franchising, particularly in its weakest businesses, meant FRG captured little of the stable, fee-based revenue and risk transfer typical of a true franchisor, while assuming significant leverage and full exposure to operational downside.

The remaining businesses were comparatively more resilient but still faced headwinds. PSP benefited from recurring pet spending and a functioning franchise model, with EBITDA margins remaining stable at nearly 9% [2]. Nonetheless, these were still alarmingly low margins for a business with over 65% franchised locations, likely indicating that franchise royalty income was insufficient to offset the drag from company-owned stores. The Vitamin Shoppe’s sales were supported by ongoing wellness demand, but it faced sustained competition from mass retailers and e-commerce platforms, with margins remaining at around 11%. These two were FRG’s best performers, but this relative strength was insufficient to offset its other declining businesses, resulting in a 44% year-over-year decline in total adjusted EBITDA across 1H 2023, prompting FRG to pursue strategic alternatives.

Prepetition Initiatives

Take-Private Transaction

Facing declining operating performance in early 2023 and seeking greater flexibility to restructure away from public markets, FRG soon became the target of a take-private proposal. In March, FRG announced it was executing a management buyout led by CEO Brian Kahn and in partnership with other senior management, B. Riley Financial, a financial services company, and Irradiant Partners, an alternative investment manager, to acquire the 64% of FRG’s outstanding common stock not already controlled by management, for a price of $30 cash per share, a 31.9% premium to FRG’s closing stock price of $22.74 on March 17, 2023 [10]. The transaction closed in August 2023, valuing FRG at $2.8bn [11].

The take-private transaction created a new, layered corporate structure. A newly formed entity, Freedom VCM, became the holding company (“HoldCo”) and acquired 100% of FRG’s equity, with FRG continuing to operate as the operating company (“OpCo”). Another newly formed entity, Freedom VCM Interco, was established as the parent entity of the HoldCo (“TopCo”).

The transaction was financed with $216.5mm of new equity contributed by B. Riley, representing a 31% equity interest in the TopCo worth $281mm, and $280mm in additional equity capital from other investors. CEO Brian Kahn financed his personal equity rollover with a separate $200mm loan from B. Riley secured by his FRG shares, rendering him effectively doubly levered with a total ownership stake of 32.4% [12]. The remainder of FRG was primarily owned by coinvestors and other members of the management team. In addition, FRG raised roughly $500mm of new debt through a term loan facility issued at the HoldCo level (the “HoldCo Term Loan Facility”) [13] [14]. This debt was provided by a lender group that included PIMCO, a large global investment manager, and Irradiant [11]. Post-take-private, FRG’s preexisting corporate debt remained at the OpCo level, while the newly incurred term loan sat separately at the HoldCo. The TopCo was designated as the guarantor of the term loan. This separation of debt across the corporate structure created differing creditor priorities, a dynamic that would become central in the near future [1].

Figure 7: Pro forma corporate structure [1]

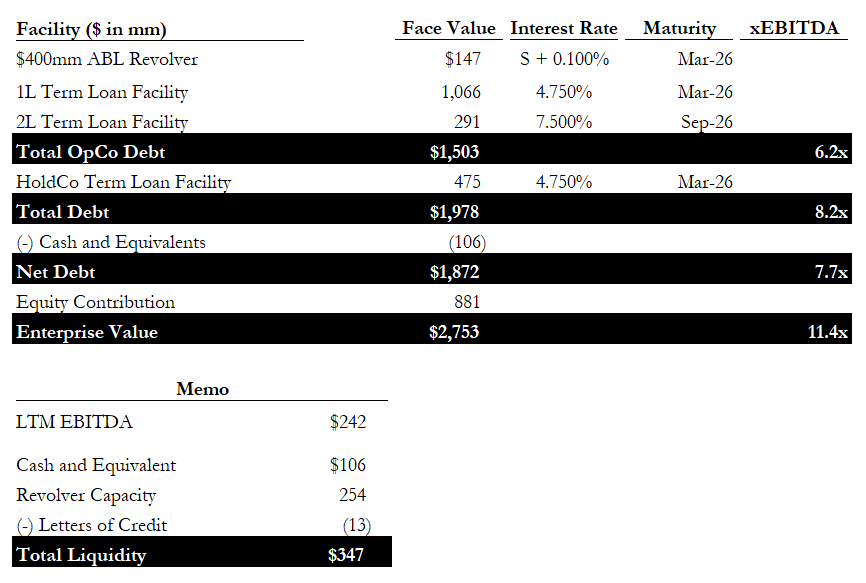

Pictured below is FRG’s pro-forma capital structure, post-take-private. The buyout increased FRG’s leverage by nearly two turns of EBITDA, and it also included a ~$300mm injection of new capital into the company [11].

Figure 8: Take-private pro forma capital structure, August 2023 [2]

Divestment of Badcock and Sylvan

FRG also explored a number of strategic alternatives in an effort to increase liquidity and deleverage its balance sheet. In April 2023, the company explored a potential sale of The Vitamin Shoppe, arguably its best-performing business, and, separately, of Buddy’s. Neither of these transactions ultimately went through. Later in September, FRG discussed a whole-business securitization of PSP, a structure that pledges substantially all operating assets and cash flows to support asset-backed debt, effectively ring-fencing the business to raise financing (see our write-up for an in-depth explanation) [1]. This was the most promising avenue to raising new money, and negotiations progressed into late 2024.

However, in the absence of any near-term solutions, FRG instead relied on actions involving Badcock and Sylvan. Roughly two years after acquiring Badcock in November 2021, FRG divested the business through a transaction that combined it with Conn’s, a competitor. It was an all-stock deal valued at $74.5mm in which FRG received convertible preferred shares that were convertible into non-voting common stock representing 49.99% of Conn’s outstanding common stock [15]. For clarification, this did not mean Conn’s market cap was around $150mm, just that the value of the preferred share package was worth $74.5mm, which includes the underlying common share value and the convertible option value. Conn’s market cap at the time of the transaction was only $80mm. This sale represented a huge discount to the $580mm that FRG paid to acquire Badcock in 2021, indicative of how much the business had deteriorated since then, made worse by the fact that FRG received consideration in the form of stock, which was relatively illiquid and volatile in value, rather than cash.

However, while the divestiture did reduce FRG’s exposure to Badcock’s liquidity and capex needs, it did not come without additional cost. Under FRG’s HoldCo credit agreement, certain actions, such as asset sales, were restricted unless the lender group provided prior approval. These “consent rights”, which are standard provisions within credit documents designed to protect lenders from actions that could impair their collateral, allowed the HoldCo lenders to block the divestiture until they consented. As FRG’s performance weakened, the lenders exercised these rights to extract tighter covenants and a higher interest rate as a condition to approving the Badcock sale, thereby increasing FRG’s interest expense in exchange for consent [1].

A couple months later, in February 2024, FRG sold Sylvan Learning for $185mm to Unleashed Brands in an all-cash deal [16]. Given that FRG purchased Sylvan for $83mm back in 2021, this was a great outcome that generated much needed liquidity. The sale and the Badcock divestiture marked a clear shift in FRG’s strategy towards improving its liquidity position [1]. We estimate cash burn of ($25mm) in 2H 2023, given that cash flow was barely positive at $19mm in the first half and FRG’s performance only continued to deteriorate, with capex remaining constant and an increase in interest expense from the HoldCo debt. Taking into consideration the sale proceeds, of which 80% went to FRG after fees and other expenses, the company had approximately $229mm in cash ($106mm - $25mm + 80% * $185mm) and $470mm in total liquidity. The company’s capital structure remained largely unchanged since the take-private, with nearly $2bn of debt outstanding and no significant maturities until early 2026.

Notwithstanding these efforts, FRG’s financial performance continued to deteriorate. In Q1 2024, FRG experienced a 12% decline in total revenues. Three of its four businesses, The Vitamin Shoppe, American Freight, and Buddy’s, experienced significant declines in revenue, with only PSP recording a slight growth of 2%. However, higher inventory and rent costs cratered PSP’s profitability, leading to a (55%) decline in operating margin [17].

As a whole, FRG’s adjusted EBITDA fell to around $25mm, down over (60%) year-over-year when adjusting for the divestitures [16]. Additionally, the company was operating with a higher debt balance with LTM leverage at 8.8x at the end of Q1 2024 as a result of the combination of the take-private, which added nearly $500mm in debt at the HoldCo level, and poor operating performance. We estimate Q1 2024 interest expense at approximately $37mm, calculated by adding the incremental interest expense from the HoldCo Term Loan to Q1 2023 interest expense (4.75% $475mm 0.25 + $31mm). We estimate capex using the average quarterly capex over the last six quarters in which FRG was a public company (Q1 2022 to Q2 2023), which amounts to just over $16mm [2]. With these assumptions, FRG’s estimated Q1 2024 cash flow (adjusted EBITDA - interest expense - capex) was ($27mm). Our estimates from earlier peg FRG’s cash balance at approximately $229mm at the beginning of 2024, meaning cash after Q1 2024 was just under $200mm. Assuming a quarterly cash burn of $32mm into the near future, which is conservative given that FRG’s performance was steadily declining, the company likely had no more than five to six quarters of liquidity remaining.

While FRG’s revolver does play a role here, with around $240mm of stated availability at the time of the take-private, that capacity was not as meaningful as it appeared. Under an asset-based lending (ABL) facility, revolver availability is determined by a borrowing base, which represents the maximum amount of cash the lender is willing to provide based on a formula tied to the company’s eligible collateral, typically its most liquid assets such as receivables and inventory. As operating performance weakened, sales slowed, and inventory turned more slowly, the value of eligible collateral would have declined, reducing the borrowing base, and therefore revolver availability. In addition, the risk of covenant or reporting breaches would have further restricted access. As a result, nominal capacity under the ABL likely overstated FRG’s true liquidity position post-take-private.

In July, as a result of these factors and risk of a covenant breach, S&P Global downgraded FRG’s credit rating to ‘CCC+’ from ‘B-’ [11]. Around this time, FRG’s 1L Term Loan, which was secured on a first lien basis against substantially all of FRG’s assets and junior only to the ABL revolver, traded down to 77 cents on the dollar [18].

CEO Brian Kahn Steps Down

Compounding these issues, shortly after the late-2023 take-private, federal prosecutors identified CEO Brian Kahn as an unindicted co-conspirator in a securities fraud case involving Prophecy Asset Management, an unrelated hedge fund. Kahn, a sub-adviser to Prophecy, was alleged to have generated and concealed approximately $350mm of trading losses over several years [19]. Following the controversy, Kahn stepped down as CEO and resigned from FRG’s and Freedom HoldCo’s boards in January 2024. The leadership transition and investigations distracted management amid acute liquidity pressure and delayed a potential PSP securitization, as counterparties required additional diligence related to the allegations [1].

New Money Proposals

After achieving limited, but insufficient, progress in generating liquidity through asset sales and amid the ongoing governance overhang, FRG engaged Ducera Partners in early 2024 and entered into discussions with its lenders to explore a potential out-of-court restructuring. Discussions occurred between an ad hoc group of lenders under the 1L Term Loan (the “1L Ad Hoc Group”) and another ad hoc group of lenders under the 2L Term Loan and HoldCo Term Loan, who called themselves “the Freedom Lenders” [1].

Multiple proposals were thrown around, including a transaction in which the Freedom Lenders would contribute $200mm in new money that would be slotted into the middle of the existing 1L Term Loan, such that the new capital structure would be $500mm 1L / $200mm new money 1.25L / $500mm 1.5L. Separately, Elliott Management, an external party with no existing position in the capital structure, discussed a potential non-pro rata LME [20].

Conn Bankruptcy

As these discussions were ongoing, in July 2024, Conn, the company that merged with Badcock, filed for Chapter 11. This raised two issues for FRG. First, although FRG had fully divested from Badcock, Conn’s did not satisfy the requirements in the Badcock lease agreements to permit a substitution of the tenant and a corresponding release of FRG’s lease guarantees. A lease guarantee obligates a third party to cover the tenant’s rent and other duties if the tenant defaults, and the guarantor is released only if the landlord approves a new tenant that fully assumes the lease. As a result of the merger, FRG remained as the guarantor of Badcock’s lease agreements. This arrangement was not an issue for FRG as long as Conn continued to meet its lease obligations. However, since Conn was in bankruptcy, if it chose to reject its Badcock leases, it may result in the landlords under such leases asserting claims against FRG as the guarantor [1].

Second, Conn’s bankruptcy effectively rendered the preferred stock FRG received for the Badcock divestiture worthless, as prepetition equity in a bankruptcy company is almost always worthless. In other words, FRG effectively divested Badcock for no economic return on a business it had purchased for $580mm, largely funded with debt, while acquiring potential guarantor liabilities [1].

Shareholder Litigation

In July, FRG became entangled in even more litigation when individual shareholders filed a lawsuit against former executives and B. Riley, alleging breaches of fiduciary duty in connection with FRG’s August 2023 take-private. The complaint alleged that B. Riley effectively acted as a nominee for former CEO Brian Kahn, meaning B. Riley acted in Kahn’s economic interest rather than as an independent, arm’s-length buyer [7].

The complaint further alleged that the $30 per share offer materially undervalued FRG, citing a Jefferies fairness opinion valuing the company at up to $38 per share and accusing Kahn and other executives of cutting EBITDA projections by roughly 50% to justify the lower valuation. The lawsuit also emphasized B. Riley’s extensive lending relationship with Kahn, stating that B. Riley made approximately $200mm in loans to Kahn between 2018 and 2023, showing the two had a longstanding relationship well before the transaction occurred [7].

In parallel, B. Riley’s share price fell sharply in August 2024, driven largely by losses tied to its investment in FRG. As FRG’s financial outlook weakened, B. Riley warned of significant markdowns on its FRG-related exposure. The firm subsequently disclosed that it expected a quarterly loss of $435-$475mm, driven primarily by those FRG-related impairments [22]. B. Riley, which initially acquired a 31% interest in the HoldCo worth $281mm as a result of the 2023 take-private transaction, wrote the fair value of its investment down to zero in September 2024 [14].

Late-Stage Lender Negotiations

By late 2024, the lender discussions from earlier proved fruitless in securing a consensual out-of-court deal. The Freedom Lender proposal failed, likely for a number of reasons. From FRG’s perspective, while the proposal would have injected much-needed capital and extended the company’s runway to pursue an operational turnaround, it amounted to a short-term fix that failed to address underlying operational issues and instead added incremental debt and interest expense to an already overlevered capital structure. Even if FRG had been willing to proceed, the transaction would have been unattractive because of the substantial litigation risk that it posed. The proposed structure would have effectively primed roughly half of the existing 1L tranche behind $200mm of new debt, potentially impairing recoveries for the subordinated 1L lenders in a subsequent Chapter 11. Those lenders would have been highly incentivized to challenge the transaction through litigation, resulting in additional legal costs, management distraction, and delays that would have further eroded value rather than stabilize the business. Separately, the Elliott-backed LME failed as parties could not agree to terms. The most promising proposal, the securitization of PSP, ultimately fell through because investors were uncomfortable with PSP’s cash-flow profile, as a meaningful portion of revenues came from volatile company-operated retail stores rather than stable, recurring franchise fees typically required to support a whole-business securitization, leaving FRG without a viable refinancing alternative. Seeing as the company no longer had the runway to continue out-of-court negotiations, FRG pivoted towards negotiating an in-court restructuring.

Shortly thereafter, in October, FRG entered into an amendment to its 1L Credit Agreement in which the 1L lenders agreed to extend the grace period before a failure to pay interest would be considered a default to November 3, 2024. In return, FRG tightened certain covenants under the agreement [20]. Additionally, FRG entered into a separate amendment under its ABL Credit Agreement to make an $18mm prepayment of outstanding principal in exchange for the ABL lenders waiving any events of default until November 3, 2024 [1].

This brief window of contractual runway bought FRG valuable time to prepare for a more structured bankruptcy filing. On November 1, 2024, FRG, the Ad Hoc Group, and other consenting 1L lenders entered into a restructuring support agreement (RSA). Around this time, FRG’s 1L Term Loan was quoted at 64 cents [18]. Two days later, on November 3rd, FRG filed for Chapter 11 in Delaware with just $14.3mm of cash on hand [1].

Prepetition Capital Structure

FRG entered Chapter 11 with just under $2bn of total funded debt, the majority of which – nearly $1.5bn of it – was incurred at the FRG entity, the OpCo. The remaining $515mm of it consisted entirely of the HoldCo Term Loan Facility, which was issued at Freedom VCM, the HoldCo. This corporate structure reflects a classic HoldCo–OpCo arrangement, where all of the operating assets, namely FRG and its franchisor businesses, resided at the OpCo, while the HoldCo owned 100% of the OpCo equity, alongside its own corporate debt.

Figure 9: Prepetition capital structure [1] [20]

Under this structure, OpCo lenders held direct claims on the operating assets and cash flows of the business. In contrast, HoldCo lenders had claims only against the HoldCo, whose sole meaningful asset was its equity interest in the OpCo. This meant that the value of OpCo equity existed only after OpCo lenders were paid in full. Accordingly, HoldCo lenders were structurally subordinated to OpCo lenders: they could recover value only if there was residual equity value remaining at the OpCo level after satisfying the $1.5bn of OpCo debt.

Because prepetition equity is often heavily impaired or wiped out in bankruptcy, HoldCo lenders faced a high risk of limited or no recovery unless OpCo enterprise value materially exceeded OpCo liabilities. As we will explore later on, this dynamic placed FRG’s HoldCo lenders in a weak economic position from the outset and set up conflicts between them and FRG and the 1L Ad Hoc Group.

Our analysis notes that FRG appeared to have roughly $152mm of liquidity at the Chapter 11 filing, consisting of $14mm of cash and $138mm of revolver availability based on a $400mm ABL with $249mm drawn and $13mm of letters of credit outstanding. However, similar to as we discussed earlier, FRG’s usable liquidity was likely well below the revolver’s headline availability. Because ABL borrowing capacity flexes with the value of eligible collateral, weakening operations and slower inventory turnover would have reduced the borrowing base, while heightened covenant and reporting risks further constrained access. As a result, nominal ABL capacity likely overstated FRG’s true liquidity at the petition date.

Chapter 11

Restructuring Support Agreement

FRG structured its RSA with two potential “plans of action”. The first option was a section 363 sale of substantially all of the company’s assets (the “Sale Transaction”). Under this framework, only bids that provided for the full cash repayment of the DIP Facility, the ABL Facility, and the 1L Term Loan would be considered. The second option was a standard Chapter 11 plan where the 1L lenders would take ownership of the company and continue operating it as a going concern (the “Plan Transaction”).

Under the Plan Transaction, the 1L lenders would be fully equitized and receive 100% of the post-reorganization equity, subject to certain dilutions. The 2L lenders would receive new 5-year warrants to purchase up to 5% of the post-reorganization equity, while the HoldCo lenders would receive no consideration. American Freight would be liquidated under both frameworks [1].

Although the disclosure statement did not provide an explicit baseline equity valuation, we constructed a rough estimate of FRG’s equity value at emergence. Using the disclosure statement’s 2025 EBITDA estimate, we apply a 10% uplift to reflect depressed in-bankruptcy performance, arriving at a normalized 2025 EBITDA of $182mm (which excludes American Freight). Applying a 7.5x EBITDA multiple – toward the low end of FRG’s historical 7-9x trading range prior to margin compression from rising leverage and declining profitability – implies an enterprise value of approximately $1.4bn, half of the $2.8bn valuation that FRG commanded in its 2023 take-private. After subtracting estimated net debt at emergence of $361mm (discussed further below), we estimate equity value of roughly $1.0bn, implying that the 2L lenders were offered the opportunity to purchase an equity stake worth approximately $50mm, in contrast to a total claim size of $125mm. Additionally, the RSA provided for a $750mm DIP facility consisting of $250mm in new money and a $500mm roll-up of amounts under the 1L Term Loan [23].

In accordance with the Sale Transaction, FRG began a postpetition marketing process after entering Chapter 11. While a sale of substantially all of the company’s assets was preferred, FRG was also open to individual bids for its businesses, of which the proceeds would go towards funding a restructuring adhering to the Plan Transaction [20]. Note that as opposed to the two plans being competitive with each other, it was implied that the debtor and 1L lenders prioritized effectuating a Sale Transaction, and would resort to the Plan Transaction as a second option. As discussed in the following section, the 2L and HoldCo lenders had little reason to favor either plan, as both allocated minimal or no recovery to them and were therefore equally unattractive.

Freedom Lender Objections

While the RSA reflected a consensus among FRG and its 1L lenders, it was immediately contested by other creditor constituencies. For holders of the 2L Term Loan and the HoldCo Term Loan, particularly the Freedom Lender group, the terms of the RSA were unacceptable.

As a result, the Freedom Lenders, led by PIMCO and Irradiant, who collectively held 93% of the $517mm HoldCo Term Loan, pursued a highly litigious, “scorched earth” strategy to challenge key aspects of the RSA and generally disrupt the Chapter 11 process in order to extract holdup value [24]. In bankruptcy, holdup value arises when junior creditors use litigation to impose costs on the estate, increasing pressure on the debtor and senior creditors to provide for better plan terms in order to avoid further erosion of estate value. Moreover, extracting improved terms was particularly important for Irradiant because the HoldCo Term Loan represented a large portion of its fund’s invested capital, so taking a zero on the investment would undoubtedly have severe consequences for the fund [20].

Shortly thereafter, the Freedom Lenders moved immediately to challenge the DIP structure proposed under the RSA during FRG’s first day motions. Specifically, the group argued that the 2:1 rollup feature was too aggressive and the rate of SOFR + 1000 was too high [25].

As the case progressed, the scope of the challenges expanded. In late November, the Freedom Lenders filed three additional requests with the court. First, they sought to terminate FRG’s plan exclusivity period. Plan exclusivity gives a debtor the exclusive right to file and solicit a plan for an initial 120 days after the case begins (can be extended up to a maximum of 180 days). The Freedom Lenders argued that the RSA-backed plan was unconfirmable because they intended to vote against it, and since they held a majority position in the HoldCo voting class (93%), their rejection would carry the class. They argued that ending exclusivity would allow competing proposals to be voted on, giving them an opportunity to propose their own plan, one they believed was easily confirmable [24]. Proposing their own plan would allow the Freedom Lenders to set the starting point for negotiations and potentially extract a better outcome [26].

Second, the Freedom Lenders moved for relief from the automatic stay. In Chapter 11, the automatic stay generally pauses creditor enforcement actions against the debtor, including efforts to repossess collateral and continue litigation, while the bankruptcy proceeds. In exchange, debtors are typically required to provide “adequate protection” to secured creditors if their collateral is at risk of losing value. The Freedom Lenders argued that their HoldCo collateral, which consisted solely of common equity in OpCo, was not adequately protected because the RSA proposed transferring their collateral to the DIP lenders and 1L group by allocating these parties 100% of the post-reorganization equity [26] [24].

Third, the Freedom Lenders requested the court to appoint a Chapter 11 trustee to oversee the bankruptcy process. In Chapter 11, a trustee is a court-appointed independent fiduciary who can take over key management powers from existing leadership. In most cases, the company operates as a debtor in possession (DIP), meaning existing management continues to operate the company and acts as its own trustee. This right is only waived if the court deems the debtor to be acting in bad faith or with a material conflict of interest, which the Freedom Lenders argued to be the case for FRG [24].

These efforts ultimately proved unsuccessful. During a hearing in late December, the court denied each of the Freedom Lenders’ motions. First, Judge John Dorsey concluded that the Freedom Lenders had not demonstrated that an alternative transaction would better maximize value for creditors. Second, the Freedom Lenders’ argument that their collateral required protection through lifting the automatic stay made little sense, as their common equity in OpCo was likely already worthless at the petition date, and adequate protection serves only to protect against a postpetition decline in the value of a secured creditor’s collateral, not to protect against losses on the overall claim. Finally, there was insufficient evidence to support the appointment of a trustee. Judge Dorsey also approved the DIP and its 2:1 roll-up [26].

Global Settlement

Although the court rejected these motions, the litigation campaign did not end. The Freedom Lenders continued litigating against nearly every substantive filing into early 2025. Their goal was not to win in court, but to make the sustained litigation as costly as possible, in hopes that the debtor and 1L lenders would eventually concede more favorable recovery terms. By March, the case had effectively stalled, with Josh Sussberg of Kirkland & Ellis, counsel to the debtors, stating that “‘the debtors are going in circles with their creditors while burning cash on professional fees.’” FRG was also still dealing with the shareholder lawsuit over the take-private. Allowing these lawsuits to work their way through the courts was unappealing, as each additional day in bankruptcy further eroded estate value, diverting recovery away from creditors [21].

Against this backdrop, the debtors determined the best path forward was a global settlement, a comprehensive agreement resolving multiple interrelated disputes in a single package rather than through prolonged litigation. Such settlements are typically implemented through a Bankruptcy Rule 9019 motion, which requires court approval and a finding that the compromise is fair and in the best interests of the estate. By pursuing a global settlement, the debtors aimed to halt the onslaught of Freedom Lender litigation, preserve remaining estate value, and create a clearer path toward plan confirmation [20].

That decision was formalized the following month in April, when FRG filed a global settlement with the bankruptcy court to resolve the outstanding disputes among the debtor, the 1L Ad Hoc Group, and the Freedom Lenders [28]. The company also announced that it had secured a buyer for The Vitamin Shoppe. Under the settlement, ABL lenders would be repaid from a combination of cash proceeds from the pending The Vitamin Shoppe sale and borrowings under a new ABL facility. The 1L lenders received 100% of the post-reorganization equity. The DIP lenders, with claims totaling $784.9mm, received recovery through a combination of $445mm in take-back term loans and the conversion of the remaining approximately $340mm into post-reorganization equity at a 25% discount to FRG’s total reorganized equity value, representing a 57% recovery from debt [29] [20].

The 2L lenders received different recoveries depending on whether they were members of the Freedom Lender group. Both the Freedom Lender and Non-Freedom Lender 2Ls received $25mm of post-reorganization equity and a stake in a new litigation trust created by the settlement to pursue potential claims surrounding the take-private. On top of that, only the Freedom Lender 2Ls received $15mm of cash. HoldCo lenders also received an interest in the litigation trust, representing a variable recovery dependent on the outcome of the litigation. The trust was funded with $13.3mm of cash from the TopCo, with any potential litigation proceeds distributed 58% to 2L and HoldCo lenders, 30% to 1L lenders, and 12% to OpCo general unsecured creditors [20]. Given the inherent uncertainty, costs, and settlement dynamics of the litigation, ultimate recoveries are expected to be significantly lower than the headline claim amounts and likely range from minimal settlement value to no recovery at all. In exchange, the Freedom Lenders agreed to withdraw and permanently stay all litigation, including their appeals of the final DIP order and the termination of plan exclusivity ruling [28].

Sale of The Vitamin Shoppe

With the global settlement in place, attention shifted to completing the sale of The Vitamin Shoppe, which was critical to funding the settlement. Although the formal auction process did not yield any qualifying bids, meaning bids that met the minimum price, financing requirements, and other conditions set by the seller, the debtors continued discussions with two potential buyers following the auction, ultimately reaching an agreement on final terms. In May 2025, FRG received court approval for its section 363 sale of The Vitamin Shoppe to Kingswood Capital Management, a middle-market private equity firm, and Performance Investment Partners, a private investment firm focused on consumer and retail businesses, for $194mm, implying a ~1.4x multiple on 2023 EBITDA (latest available figure) [30]. For context, FRG had acquired the Vitamin Shoppe in late 2019 for $208mm, implying a 3.2x multiple of 2018 EBITDA, though the depressed sale multiple reflects the distressed nature of a Chapter 11 sale [20]. The sale represented a key milestone in the case, as the proceeds were central to supporting the global settlement, which the bankruptcy court approved shortly after the transaction closed in late May [31] [32].

Exit from Chapter 11

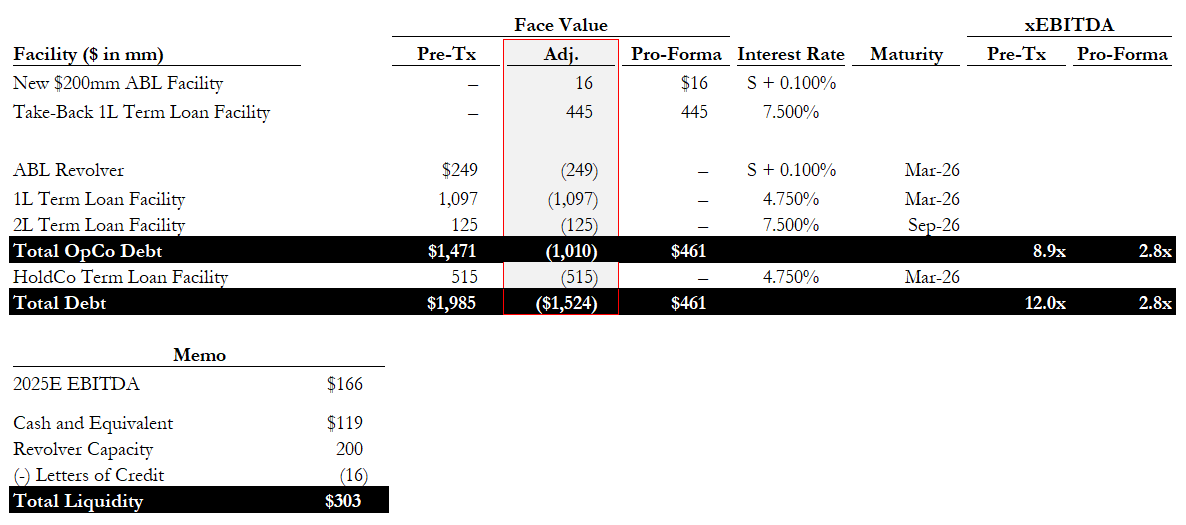

Finally, with the global settlement approved, FRG moved to exit bankruptcy. After seven months in Chapter 11, FRG’s plan of reorganization was confirmed on June 2, 2025, and the company emerged from bankruptcy on June 6th as a newly created private company called Fusion Parent, primarily owned by the DIP and 1L lenders. Fusion would continue operating two businesses, PSP and Buddy’s [33]. The exit capital structure consisted of a new $445mm Take-Back 1L Term Loan Facility and a new $200mm ABL Facility, with $16mm drawn at emergence [20]. The restructuring equitized over $1.5bn of prepetition debt.

Figure 10: Bridge capital structure [20] [34]

The company’s new capital structure put leverage at a manageable 2.8x, based on the projected 2025 EBITDA of $166mm [34]. However, the macroeconomic environment for brick-and-mortar retail continued to be challenging, and the reorganized business was more concentrated with fewer operating banners, leaving it exposed to downside risk despite lower leverage.

Final Thoughts

Since emerging from bankruptcy, limited information is available regarding Fusion’s performance. However, in early December, Buddy Mac Holdings, one of Buddy’s largest franchisees operating 47 locations, filed for Chapter 11. This filing reflects the ongoing challenges facing Buddy’s and the broader furniture retail market. For Fusion, the bankruptcy not only reduces franchise royalty income but also raises concerns about potential stress across its nearly 300 franchised Buddy’s locations. Also in December, Pet Supplies Plus announced that it was separating from Fusion and to continue operating independently [35]. With the exit of PSP, Buddy’s became the sole remaining business in Fusion’s portfolio, bringing the roll-up experiment to an end. However, much can be learned from FRG’s Chapter 11, as it illustrates three broader lessons about franchisor roll-ups, capital structure design, and creditor behavior in distress.

First, the case highlights the limits of FRG’s business model. While a franchise-based strategy can appear attractive on paper, offering asset-light growth and recurring royalty income, FRG’s portfolio was anchored in structurally challenged, brick-and-mortar retail categories. Most of its businesses operated in low-differentiation segments facing secular pressure from e-commerce and changing consumer behavior. Compounding this issue, FRG operated a large number of company-owned locations alongside its franchised stores. These corporate stores exposed the company directly to the aforementioned operating risks associated with brick-and-mortar retail, undermining the defensive characteristics that franchising is often assumed to provide.

Second, the bankruptcy underscores the importance of structural subordination. The post-take-private HoldCo–OpCo structure left the Freedom VCM HoldCo lenders structurally subordinated to nearly $1.5bn of OpCo debt, with recovery dependent entirely on residual equity value. In distressed situations, this becomes a problem for the HoldCo lenders as the OpCo enterprise value is often insufficient to clear the OpCo capital stack, leaving the HoldCo claims deeply out of the money. The case reinforces that where debt resides within the corporate structure can be as important as collateral or covenants in determining recoveries.

Finally, FRG demonstrates how out-of-the-money creditors can still exert influence through aggressive litigation. Despite the Freedom Lenders being clearly out of the money, as evidenced by their attempt to insert a $200mm rescue loan in between the 1L Term Loan (indicating that they believed value broke at a point higher in the capital structure than their subordinated 2L and HoldCo claims), they pursued a scorched-earth strategy, throwing desperate challenges against everything to obstruct the bankruptcy process. Ultimately, these efforts were successful in extracting marginally better recoveries for the group, but remain debatable whether they were worth the additional time, effort, and legal expenses. More importantly, the Freedom Lenders illustrate how out-of-the-money creditors can take advantage of the inefficient and bureaucratic Chapter 11 process to extract holdup value, even when substantive recovery prospects are limited.

This analysis is provided for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice, legal advice, tax advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security. The content reflects the author's opinions and estimates based on available information and should not be relied upon as the sole basis for any investment or legal decision. Readers should conduct their own due diligence and consult with qualified financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decisions. Past performance and historical analysis do not guarantee future results.