Welcome to the 175th Pari Passu newsletter.

In today’s edition, we’re turning to Del Monte Foods, the 139-year-old canned fruit and vegetable icon that filed for Chapter 11 in July 2025. Del Monte, a market leader in shelf-stable foods, has an extensive corporate history, including ownership by KKR and TPG, and a role in an infamous leveraged buyout you’ve probably read about. In recent years, the company has struggled with shifting consumer preferences and a challenging macroeconomic environment, leading to both a contested liability-management exercise and a Chapter 11 filing.

In August 2024, Del Monte and participating lenders launched a dropdown LME that raised new money to help fund its working capital needs, but less than a year later, the company filed for bankruptcy, with a much different capital structure. Del Monte serves as a compelling case study on the limitations of LMEs and their effects on subsequent in-court filings.

In this writeup, we’ll walk through Del Monte’s business model, brands, and rich corporate history, before detailing the catastrophic inventory mistiming and liquidity crunch that led to the company’s distress. We’ll then cover the 2024 LME mechanics and the legal strategy holdouts used to reach an eventual settlement. From there, we’ll dive into the Chapter 11 proceedings, the sale process, and the massive shift in value engineered by the Ad Hoc Group’s DIP proposal.

NVIDIA and the Structural Investments Fueling the AI Buildout

The proliferation of AI tools and platforms isn't just a fleeting trend; it marks a foundational shift in how computing infrastructure is built.

Discover how a new wave of AI investment is driving an unprecedented technology buildout, and examine whether NVIDIA can maintain its market dominance through its full-stack hardware and software ecosystem.

Del Monte Overview

Del Monte Foods is one of the largest branded shelf-stable food companies in the United States. The company produces and distributes canned fruits, vegetables, broths, and other products through retail grocery, foodservice, and e-commerce channels. The company’s portfolio includes well-known pantry staples in American households, such as Del Monte canned peaches and fruit cups.

Figure 1: Del Monte’s Staple Packaged Food Products

As of July 2025, Del Monte held leading U.S. market positions across its core categories. The company is number one in market share for canned vegetables and canned fruit, holding ~23% and ~20% of these markets, respectively. Additionally, the company ranks third in canned tomatoes with a 6% share (a separate category from fruits and vegetables) and second in broth with a 9% share [1]. Notably, roughly 80% of revenue comes from canned vegetables, fruit, and tomatoes, despite efforts to diversify beyond the canned aisle.

The company’s operations are divided into three segments: U.S. Branded Retail (Del Monte’s seven owned brands), U.S. Private Label (non-branded products sold through retailers), and All Other (including foodservice, Latin America, and other miscellaneous co-packing arrangements).

Figure 2: Del Monte Brands as of 2025

Del Monte operates a vertically integrated, proximity-to-farm manufacturing model designed to minimize transportation costs and spoilage. In 2025, the company operated four production facilities, two in the U.S. and two in Mexico. Over 80% of produce is sourced within the United States, primarily within a 100-mile radius of the plants, through partnerships with hundreds of family farms. Inherently, business is seasonal, as production runs from June through September, as produce is harvested and processed in a compressed timeframe. Following this quick production cycle, inventory is sold over the following 12-18 months. To provide context, roughly 1,370 of the company’s 2,780 employees were fully seasonal and only employed during Pack Season [1]. While this sourcing strategy allows for optimal freshness, taste, and nutrition, it creates significant working capital intensity, as the company must build inventory to supply retailers year-round.

Del Monte History

Now that we’ve broadly overviewed Del Monte’s business model, let’s run through its extensive corporate history.

Del Monte’s Genesis:

The Del Monte brand began in 1886, when Frederick Tillman developed a premium coffee brand for the Hotel Del Monte in Monterey, California. At the time, Tillman ran the Oakland-based wholesale grocer Tillman & Bendel. In 1891, Tillman founded the Oakland Preserving Company and grew the Del Monte brand to include canned fruits and vegetables, starting with peaches and apricots sourced from the surrounding region [2].

In 1899, 11 of California’s largest canners combined to form the California Fruit Canners Association (CFCA). In 1916, CFCA merged with four other major packing/canning enterprises to form the California Packing Corporation, known as “Calpak”. Calpak began marketing its products under the Del Monte label, and by 1917 was using the Del Monte brand for 50 of its 72 product lines.

Over the next half-century, as technological innovation sparked increased output, Del Monte/Calpak continued to grow, becoming a household name in packaged food. A large part of this initial growth was inorganic, as Calpak acquired canning operations across the U.S. Following World War II, the company flourished as consumers purchased significantly more canned goods. By 1951, the company had an annual revenue of $223mm [2]. In the later stage of its 20th-century growth, Del Monte was increasingly focused on product innovation and brand positioning. In 1967, Calpak officially adopted the name of its leading brand, becoming Del Monte Corporation, and in 1972, it became the first major U.S. food processor to voluntarily adopt nutritional labeling on all of its food products.

The Private Equity Era:

Del Monte’s modern corporate history has been shaped by a succession of ownership changes that shaped today’s company. The first major event came in 1979, when R.J. Reynolds acquired Del Monte. R.J. Reynolds was the tobacco giant that had already diversified into food, acquiring brands like Hawaiian Punch in the 1960s. This acquisition brought Del Monte under a large corporate umbrella, strengthening the company’s distribution networks, but also exposing it to what would become one of the most infamous corporate histories in American history.

In 1985, R.J. Reynolds merged with Nabisco Brands to form RJR Nabisco, and Del Monte became part of the combined food and tobacco conglomerate. If you’ve read “Barbarians at the Gate”, you know that just three years later, in 1988, the PE firm KKR would complete its $25bn LBO of RJR Nabisco, which at the time was the largest in history. This deal, which prevailed over a rival management-led bid backed by Shearson Lehman Hutton, left RJR Nabisco with a massive debt load, requiring rapid asset sales to service.

Less than a year later, in 1989, Del Monte was carved up and sold in pieces. First, Del Monte’s fresh fruit operations, under the “Del Monte Tropical Fruit Company”, were sold to Polly Peck International for $875mm. This sale created “Fresh Del Monte Produce”, which still remains a separate entity today, and retains royalty-free rights to use the Del Monte name for fresh fruits and vegetables. After Polly Peck collapsed in 1990, Fresh Del Monte changed hands multiple times before going public in 1997 and remaining a publicly traded company today.

Additionally, Kikkoman Corporation of Japan acquired Del Monte’s processed foods operations in Asia (excluding the Philippines). The European division was also bought out by management in 1990 and renamed Del Monte International.

What remained under the RJR Nabisco umbrella was Del Monte’s U.S. canned and packaged food business. In 1990, a Del Monte management team led by Ewan Macdonald, and backed by Merrill Lynch and Citicorp, acquired these remaining U.S. operations, known as Del Monte Foods, from KKR for $1.48bn. The now-independent company was forced to divest additional assets to service its debt load, selling Hawaiian Punch to Procter & Gamble in 1990, the dried fruit division to Yorkshire Food Group in 1993, and the pudding division to Kraft in 1996. As a result of the events above, Del Monte Foods returned almost solely to its core expertise of canned fruit and vegetables.

In 1997, Del Monte Foods returned to PE ownership after being acquired by TPG for ~$800mm. Under TPG, Del Monte acquired the Contadina brand of canned tomato products from Nestlé and reacquired Del Monte Venezuela from Nabisco in 1998. However, TPG would quickly exit its investment, as Del Monte Foods went public in 1999, just two years later. The IPO raised $250mm of proceeds at an $800mm valuation.

In 2002, Del Monte underwent another large transaction when H.J. Heinz Company spun off several of its underperforming divisions, including StarKist tuna, College Inn broths, Nature’s Goodness baby food, and its American pet food business [3]. While Heinz considered these divisions underperforming, they were attractive to Del Monte as they carried higher margins than canned fruit and vegetables. These businesses were merged into Del Monte Foods in an all-stock transaction, leaving Heinz shareholders owning 74.5% and Del Monte shareholders 25.5% of the combined company. In 2008, Del Monte sold StarKist to Dongwon Enterprise Company for $363mm, stating that tuna was no longer a strategic fit and that the company would focus on pet food and produce.

In 2011, Del Monte Foods was once again taken private by an investor group led by KKR, including partners Vestar Capital and Centerview Capital (a PE fund, not the investment bank), in a deal valued at $5.3bn [3].

Three years later, in 2014, Del Monte Pacific Limited (“DMPL”), a Singapore-based company controlled by the Campos family of the Philippines through NutriAsia, acquired Del Monte Foods’ U.S. consumer products business for $1.675bn [4]. This transaction excluded Del Monte’s pet food business, which was retained by the KKR-affiliated investor group and later sold to the J.M. Smucker Company. At the time, Del Monte Foods reported annual sales of $1.8bn. The deal was financed with $930mm of debt, implying an LTV of ~56%.

The price difference between the KKR group’s $5.3bn acquisition and DMPL’s $1.675bn transaction is striking. Although DMPL did not acquire the Pet Food division, we can infer that, under KKR ownership, the company destroyed significant value. Del Monte Foods continued to operate under DMPL ownership until 2025.

The 2020s

Now that we’ve reviewed Del Monte’s business model and corporate history, let’s turn to Del Monte’s most recent decade, examining the company’s financial position. To avoid confusion, note that Del Monte uses an April fiscal year-end to capture the full packing and selling seasons. For example, FY 2024 spans May 2023 to April 2024 [5]. We’ll also refer to the “packing season”, which is when produce is harvested, processed, and canned in preparation for being sold. This typically occurs at the beginning of the company’s fiscal year, lasting from June to September. Therefore, for example, FY 2024 cash flow is used to fund the 2024 pack season (which falls into FY 2025). This dynamic will become important as we soon dive into Del Monte’s inventory management and eventual distress.

Following the DMPL acquisition, the company remained highly leveraged, with around $1bn of funded debt obligations. As consumer preferences shifted toward fresh or frozen fruit and private-label brands eroded the market share of canned fruit, Del Monte was forced to reduce its operational footprint by closing four of its 10 processing facilities [1]. Despite efforts to pivot to an asset-light model, the company continued to incur cash losses and faced a liquidity shortfall by 2020.

Around this time, the COVID-19 pandemic created both tailwinds and headwinds for Del Monte. First, as consumers began stocking pantries with shelf-stable foods, demand for Del Monte products temporarily surged, driving FY 2020 revenue to $1.53bn, from $1.42bn in 2019. However, this uncertainty also derailed a major debt deal. In early March 2020, Del Monte launched a proposed $575mm senior secured notes offering as part of a broader recapitalization, but the deal was cancelled just two weeks later due to unfavorable market conditions caused by COVID. Following this cancellation, DMPL was forced to step in with an emergency recapitalization in May 2020 [1].

DMPL contributed $387mm in equity, all of which would be used to repay acquisition-related bank debt, thereby providing investors with sufficient confidence in the issuance of $500mm of 11.875% senior secured notes due 2025. These notes were ultimately issued in May 2020 after the company’s initial $575mm offering was cancelled in March. Additionally, the company’s ABL facility, which was due in November 2020, was extended to May 2023. [6].

Following the recapitalization, Del Monte realized the benefits of its operational restructuring, cutting $68mm in annual costs and improving EBITDA to $170mm in FY 2021, more than an 85% increase from ~$90mm in FY 2020. Notably, leverage fell below 4.5x following the improvement in EBITDA, as the company used excess post-pandemic cash flow to partially repay its ABL [6].

Over the next two years, as consumers increasingly cooked at home, Del Monte’s revenue rose from $1.48bn in FY 2021 to $1.65bn in FY 2022 and $1.73bn in FY 2023, representing 11% and 5% growth, respectively [5]. Notably, for a mature canned food supplier, this growth was highly favorable.

Additionally, in May 2022, as market conditions improved and SOFR sat at just 0.5%, Del Monte refinanced its 11.875% senior secured notes with a $600mm TLB due 2028 and priced at S + 4.75%, initially representing a substantial cut in cost-of-capital, as the new TLB’s effective rate was 5.25%.

In February 2023, Del Monte issued an additional $125mm under the 2022 credit agreement. Proceeds of this incremental capital were used to partially pay down the outstanding balance under the ABL facility, while the ABL’s capacity was also increased by $125mm as part of the arrangement, from $625mm to $750mm. Therefore, this transaction resulted in a positive $250mm swing in liquidity/ABL availability.

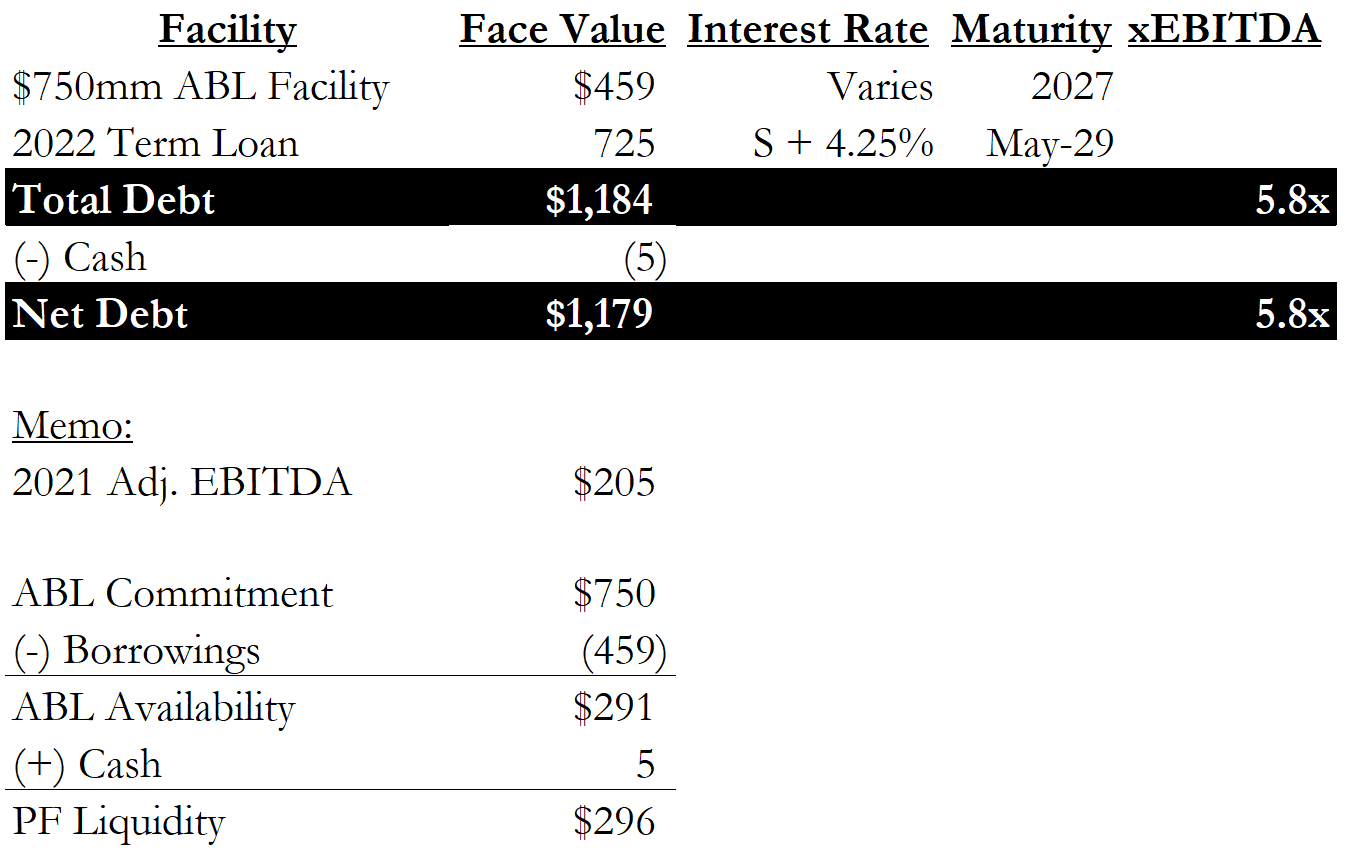

Figure 3: Del Monte’s Capital Structure as of FY 2023

Inventory Mistiming:

Building off of strong revenue growth in FY 2022 and FY 2023, Del Monte’s management made an aggressive bet that elevated consumption would continue. During the 2023 packing season, Del Monte aggressively built up inventory under the assumption that sales would continue to grow. Notably, inventory, which had previously averaged below $500mm, grew to nearly $1bn [5], coinciding with a net $355mm working capital outflow of cash in FY 2023, primarily funded by the company’s ABL facility, which, as we just covered, had recently been upsized [5].

While demand continued to grow in FY 2023, FY 2024 told a different story, as revenue increased by less than 1%, despite a notable increase in production. As a result, in 2024, Del Monte struggled to generate sufficient cash from operations to repay its ABL in preparation for the 2024 packing season. As Del Monte was forced to sell excess inventory at a discount and operating leverage worked in reverse, adjusted EBITDA fell from $205mm in FY 2023 to just $23mm in FY 2024.

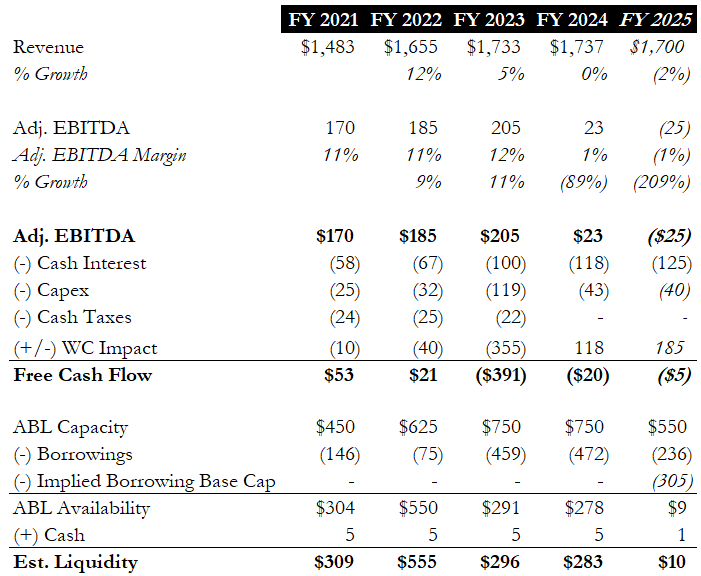

The table below details Del Monte’s financials over this period. Note that Del Monte did not report financials for FY 2025, and as a result, we’ve made a series of assumptions to approximate the company’s financial position pre-filing. First, we assumed a continued modest revenue decline of 2% to $1.7bn. Additionally, as operating leverage continued to work against Del Monte, we estimated that adjusted EBITDA continued to fall at an outsized rate, to ($25mm) in FY 2025. We also straightlined Capex and assumed the continued aggressive deferral of trade payables, resulting in breakeven cash flow, which, as we’ll see below, aligns with Del Monte’s eventual liquidity position. All of these assumptions are in italics below.

Figure 4: Illustrative Cash Burn Financials

In addition to the company’s profitability headwinds, FY 2024 also came with peak interest rates, as SOFR reached levels above 5.00%. This caused Del Monte’s interest expense to balloon to above $118mm, from $67mm in 2022, a ~76% increase over two years [1]. Additionally, with capex of $43mm and a working capital benefit of $118mm, Del Monte burned $20mm in cash. Notably, this working capital benefit stemmed primarily from deferring trade payables, resulting in a $130mm positive cash impact. Had Del Monte not deferred payments, its cash position would have looked materially worse.

In early 2024, as Del Monte struggled to sell its excess inventory, an updated collateral appraisal by ABL lenders revealed a lower net orderly liquidation value than previously assessed. As a reminder, ABL facilities cap borrowings at a borrowing base, calculated as a percentage of eligible collateral, most often inventory and/or receivables. In Del Monte’s case, as its inventory lost value, its ABL borrowing base fell below the $647mm that was currently drawn in January 2024, constituting an overdraft, an event of default under the ABL credit agreement [1]. As a result, Del Monte was forced to enter into a standstill agreement with ABL lenders as the company explored a more comprehensive solution to its liquidity issues.

Lastly, before we move to the eventual LME, it's important to highlight the fact that when Del Monte aggressively drew on its ABL facility in late 2022, it entered cash dominion with its ABL lenders. As a reminder, in an ABL credit agreement, cash dominion refers to a lender's control over the company’s cash receipts, with the goal of ensuring the borrowing base converts directly into repayment. All collections from accounts receivable are swept into a lender-controlled account and used to pay down the ABL. Funds are only released to the borrower once certain liquidity/availability thresholds are met. In theory, cash dominion should constrain a borrower’s ability to increase its ABL balance. However, as Del Monte built up excess inventory, the next year’s pack season required incremental draws at a rate faster than collections from the prior season could be swept. This dynamic will soon become important, as ABL availability directly translates to the company’s liquidity.

2024 LME

Following the events detailed above, Del Monte entered the 2024 pack season (beginning of FY 2025) in a tough liquidity position. By fiscal year end (April 2024), the ABL lenders had swept enough cash to pay down the balance to $472mm, through normal seasonal cash collections. Notably, this represented nearly $200mm of cash directed to pay down the ABL in Q4 2024. While it seems striking at first, it likely stemmed from more aggressive cash dominion paydown following the standstill agreement. However, this paydown didn’t solve the underlying problem of Del Monte’s devalued borrowing base. While exact ABL availability was not reported in Summer 2024, we can infer the company needed incremental liquidity, beyond its reduced ABL capacity, to fund the upcoming pack season. Notably, S&P estimated this shortfall in liquidity at $200mm.

To address its liquidity needs, Del Monte retained PJT Partners and Kramer Levin and turned to both third parties and a group of existing lenders, which led to the company’s 2024 liability management exercise. Following extensive negotiations with ABL lenders and the ad hoc lender group (represented by Gibson Dunn and Houlihan Lokey), Del Monte pursued a multi-step dropdown transaction that would raise $240 million in new capital, providing sufficient liquidity for the 2024 packing season. The August 2024 transaction unfolded in several steps [7]:

First, Del Monte amended its ABL credit agreement to permit a $125mm first-in, last-out (FILO) bridge loan to address immediate liquidity needs, fully backstopped by the AHG. As a reminder, under an ABL structure, a FILO loan is secured by the same base of eligible inventory/receivables but is junior to the ABL revolver. For the FILO bridge loan to receive a recovery, the ABL must first be fully repaid. Additionally, the ABL amendment reduced the ABL revolver portion of the facility's maximum balance back to $625mm, following completion of the transaction. This reduction in capacity effectively “made room” for the FILO loan, which initially shared the same collateral pool as the ABL, as total borrowing capacity under the ABL credit agreement temporarily remained at $750mm, inclusive of the $125mm FILO loan. The amendment also created DM Escrow Corporation, a new unrestricted subsidiary to which the AHG would lend an additional $115mm. Upon certain conditions being met, the escrow funds would be released and exchanged for new term loans, along with the $125mm bridge loan. Non-AHG lenders would retain the option to fund their share of new money to obtain better exchange terms, as we’ll soon detail. In total, the AHG backstopped $240mm of new money.

You are about to reach the midpoint of the report. This is where the story gets interesting.

Free readers miss out on the sections that explain:

• Exact LME Economics

• Post-LME Litigation

• Return to Distress

• 2025 Bankruptcy (RSA, Litigation, and Asset Sale)

• Creditor Recoveries

• DIP Roll-Up Analysis

• Key Takeaways

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive.

Unlock the Full Analysis and Proprietary Insights

A Pari Passu Premium subscription provides unrestricted access to this report and our comprehensive library of institutional-grade research

Upgrade NowA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Full Access to Our Entire Archive

- 150+ Reports of Evergreen Research

- Full Access to All New Research

- Access to the Restructuring Drive

- Join Thousands of Professional Readers