Welcome to the 160th Pari Passu Newsletter,

In today’s edition, we’re diving into another company that fell victim to the pandemic. This time, however, it's not a classic brick-and-mortar retail case. Instead, we will be looking at Washington Prime Group, a real estate investment trust that was formerly one of the largest owners and operators of shopping malls across the U.S.

Initially formed as a spin-off from Simon Property Group, the largest and premier U.S. operator of shopping malls, in 2014, Washington Prime Group spent much of its existence fighting an uphill battle against the transition toward digital retail. As we will explore today, while prudent management allowed the company to stay relatively profitable, the pandemic proved to be a death sentence, fast-tracking it into Chapter 11.

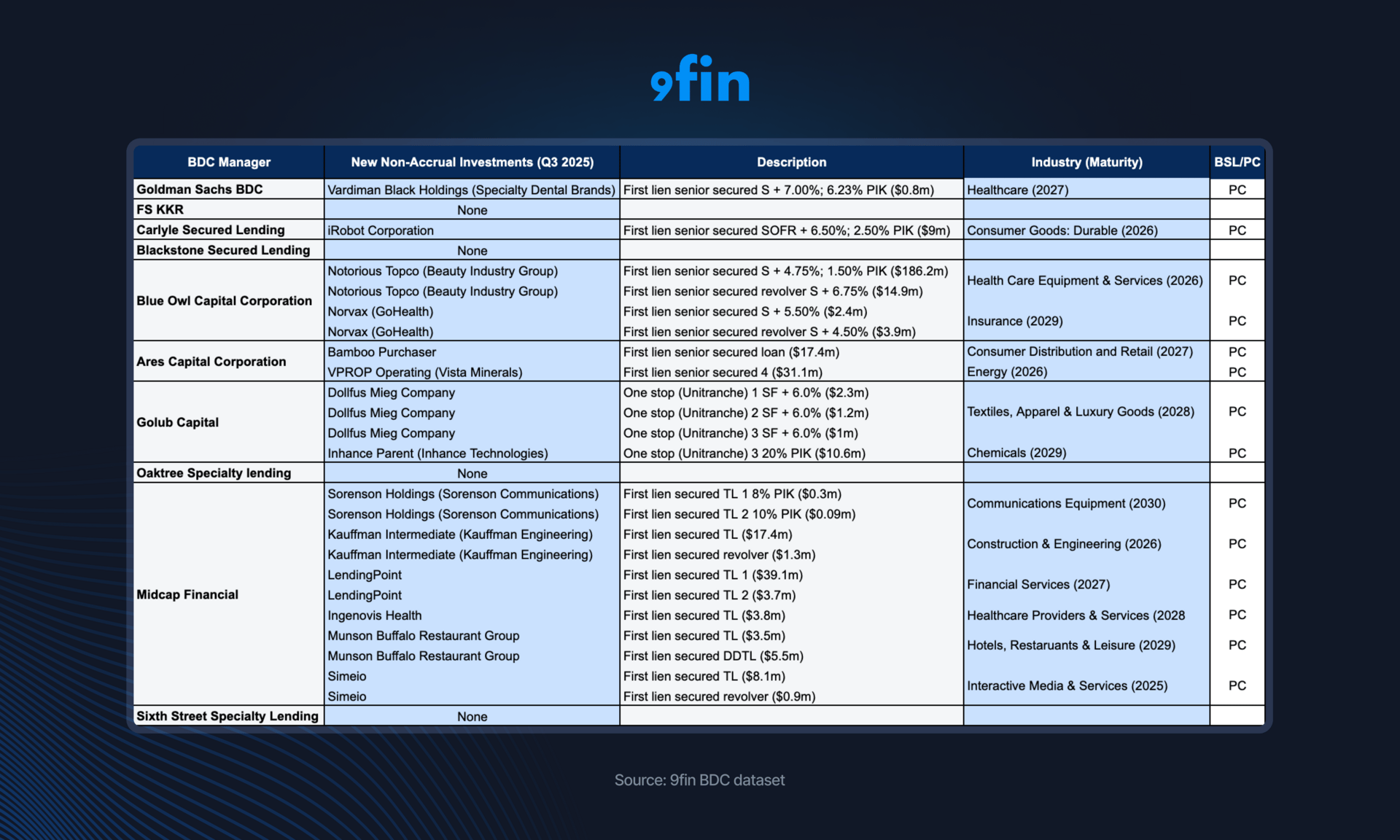

Exclusive 9fin data drop for Pari Passu subscribers

9fin's latest research reveals the worst-performing BDC loans, exposing hidden distress in the booming $1.6T private credit market.

The results are revealing: four of the ten largest BDCs are claiming they have NO new non-performing loans. FS KKR, Blackstone Secured Lending, Oaktree Specialty Lending and Sixth Street Specialty Lending have no new loans on non-accrual status despite one of the most torrid quarters for trading that BDCs have known.

This analysis represents the only systematic tracking of non-accrual trends across the industry, made possible by 9fin's unique dataset of 7,000+ BDC loan holdings. This data is presented in one searchable dataset, delivering comparable performance insights previously impossible to obtain at scale.

We've released this data exclusively for Pari Passu subscribers ahead of anywhere else. For full access to the report, plus BDC tear sheets, First Brands BDC analysis, and more, request a free trial.

Pari Passu subscribers are eligible for a 45 day free trial of 9fin — that’s 15 days longer than usual. Click here to learn more about the offer.

Overview of the REIT Industry

Before we dive into the company’s history and path into distress, it’s helpful to first understand the REIT industry at a high level and how these vehicles give investors access to commercial real estate. A real estate investment trust (REIT) is a company that owns, operates, or finances income-producing real estate. It functions like a mutual fund for real estate: investors pool capital into REITs, which use that capital to manage real estate portfolios. The purpose of REITs is to provide retail investors with an easy way to gain exposure to commercial real estate without needing to directly own or manage individual properties [1].

There are generally three types of REITs [1]:

Equity REITs: Equity REITs own and operate income-producing real estate directly, such as offices, malls, apartments, warehouses, hotels, healthcare facilities, or data centers. Their revenue comes primarily from rental income, with long-term leases providing stability, and from appreciation of the underlying property over time. Equity REITs often specialize in a certain type of real estate. Examples of publicly traded equity REITs include Prologis (industrials and logistics), Simon Property Group (retail), and Equinix (data centers).

Mortgage REITs: Mortgage REITs do not typically own the properties themselves. Instead, they finance real estate by purchasing or originating mortgages and mortgage-backed securities, earning income from the interest spread between their borrowing costs and lending yields. This model makes them highly sensitive to changes in interest rates and generally more volatile than equity REITs. Two main upsides of mortgage REITs are higher dividends, because they use leverage to amplify the interest spread, and fewer property hassles, because they hold loans and/or bonds rather than operating buildings, avoiding tenants, repairs, and large capex spend.

Hybrid REITs: Hybrid REITs combine aspects of both models, owning properties directly while also investing in or financing mortgages, allowing them to diversify revenue streams across rental and interest income.

Equity REITs are the most abundant of the three, and will be the focus of today’s write-up. On a high level, these companies acquire and develop properties, lease them to tenants, and then collect rental income. Certain equity REITs may also earn income by providing non-core services to tenants, such as property operating services [1] [2].

All REITs must comply with strict legal and tax requirements set by the IRS. Most importantly, at least 75% of gross income must come from real estate-related sources, including rental income, mortgage interest, and property sales, and at least 90% of taxable income must be distributed to shareholders as dividends annually [1].

Meeting these thresholds allows REITs to qualify as tax-advantaged pass-through entities, exempting them from corporate income tax on qualifying real estate income. Without REIT status, a real estate company would pay corporate tax on its profits, and shareholders would then pay tax again on dividends, meaning the same income gets taxed twice. With REIT status, the company avoids corporate tax, so the income goes straight to shareholders and is taxed only once. This single layer of taxation makes REITs a more efficient way to channel real estate income to investors. However, note that REITs are still responsible for other taxes, including local property taxes on their buildings and corporate tax on income earned through taxable REIT subsidiaries that provide non-core services [1].

While having the tax-advantaged status allows REITs to distribute returns to investors more effectively, adhering to the IRS’s dividend distribution requirement means that REITs must fund growth primarily by raising new capital, either through the debt or equity capital markets, as opposed to reinvesting profits. This reliance on external financing can become a risk if capital markets tighten, interest rates rise, or investor appetite for new issuances weakens. Additionally, an overdependence on debt financing can leave a REIT with a highly leveraged balance sheet, increasing vulnerability to downturns in property values or rental income [1].

Real Estate Property Quality

An important distinguishing feature between REITs is property quality. In real estate, properties are informally bucketed into Tier 1 (“A”), Tier 2 (“B”), and Tier 3 (“C”) based on productivity and durability of cash flows. These ratings are not a GAAP standard but market shorthand. Tiering is dependent on sales per square foot (psf), rent levels and whether rents rise on renewals, how full the center is, the share of a store’s sales that goes to occupancy costs, the strength of the surrounding area (household income, population, growth), the mix and drawing power of the stores and services on site, and the property’s condition. Landlord costs to land tenants, such as assisting with property buildout, tenant allowances, and leasing commissions, and the amount of time that space sits vacant also factor in [3]. For context, tenant allowances are landlord-funded contributions that help tenants build out or refurbish their space, typically measured on a square footage basis, and recorded as part of capex. Leasing commissions are fees a REIT pays brokers to sign or renew tenants at its properties [4].

In the context of retail REITs, a Tier 1 center is typically in a popular, high-income area with steady customer traffic and recognizable national brands (e.g., an Apple store, a high-end grocer, busy restaurants, a modern cinema). Shops sell a lot psf, vacancies are rare, rents are high, and empty space is re-leased quickly to new tenants with modest landlord spending. Tier 2 is a solid but average center – think some national chains and local shops, decent demographics and traffic, where sales are moderate, vacancies take longer to fill, and landlords spend more to ready space. Tier 3 is a struggling center, often in a lower-income or shrinking trade area, with more empty storefronts, more discount or short-term tenants, and fewer destination brands. Sales and rents are low, and new leases typically require heavy concessions. Naturally, retail REITs want to own and operate as many Tier 1 properties as possible [3].

Company Overview

With this overview in mind, our write-up today focuses on Washington Prime Group (“WPG”) is an equity REIT with a focus on enclosed retail shopping malls and open-air properties (outdoor shopping centers with exterior-facing store entrances and uncovered common areas) across the U.S. It was formed in 2014 as the result of a spin-off transaction from Simon Property Group, a major U.S. retail-focused equity REIT with ownership or economic interests in over 325 properties and revenues of $4.9bn, after considering the divestment. WPG owned and operated 97 retail properties at its founding, and began trading on the NYSE after the spinoff [5].

After the spinoff, WPG began expanding via a series of strategic acquisitions across 2014 and 2015 that would increase its total properties owned to 121. However, beginning in 2016, the company shifted course and reduced its property footprint in response to the challenges facing brick-and-mortar retailers, particularly pressure from growth in online competitors, such as Amazon. To adjust, WPG executed various sales and transfers of properties to certain lenders, bringing its portfolio down to 104 properties by 2019. Despite these pressures, WPG maintained an occupancy rate of ~92% across its property portfolio, which was roughly in line with the national average shopping center occupancy rate of ~94% in 2019 [5] [6].

Portfolio Overview

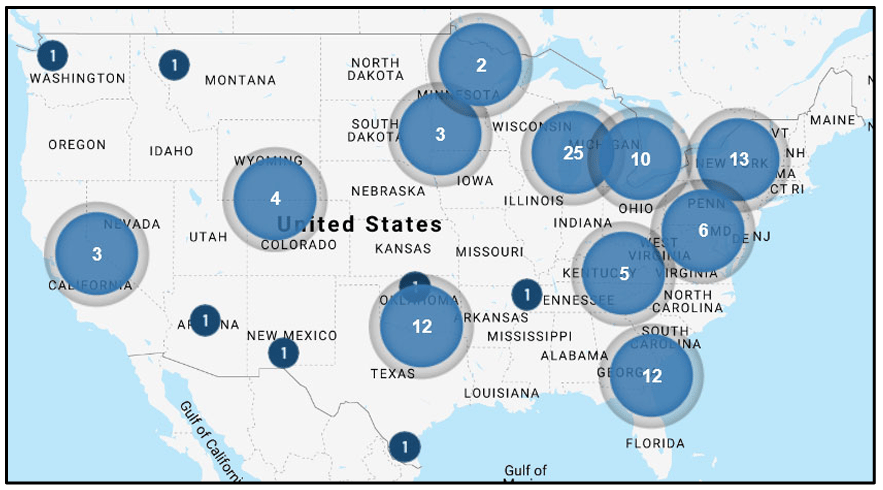

By the beginning of 2020, WPG’s portfolio fell to 102 properties, which were spread across the U.S., including certain properties in Hawaii. In total, the company managed over 53mm square feet of gross leasing area (GLA), which refers to the rent-generating space that tenants actually occupy inside the stores, and excludes the shared corridors, lobbies, or mechanical rooms [2].

Figure 1: Map of WPG’s properties

A majority of these properties were wholly owned by WPG; however, a handful of the properties were held through joint ventures and other third-party arrangements. WPG’s properties were primarily outfitted as enclosed or open-air shopping centers, so their tenants were primarily retailers, including anchor stores (like Macy’s and Bloomingdale's), big box tenants (like Walmart and Target), restaurants, movie theaters, and regional or local retailers [2].

WPG’s portfolio skewed toward mid-tier and secondary assets, with 41 Tier 1 properties and 61 Tier 2 and Tier 3 locations. Peers like Simon Property Group have upwards of 60-70% of their portfolio classified as Tier 1. For WPG, that meant many centers in average or lower-income trade areas, lower sales psf for smaller shops, more vacancy and downtime, and greater landlord spending to land replacement tenants. This quality mix is important for later sections: it helps explain softer rent growth, heavier leasing incentives, and why backfilling vacant space grew harder as retailer closures accelerated.

Figure 2: Polaris Fashion Place in Columbus, Ohio, a WPG property [2]

Business Model

WPG derives the majority of its revenue from rental income from its tenant leases. Rental income contracts are structured as either a fixed minimum rent, under which tenants pay a minimum rent based on rented square footage, plus overage rents that are paid when a tenant’s sales exceed an applicable sales threshold, or as a percentage rent arrangement, under which payments are linked to a tenant’s sales performance, resulting in higher rent when sales exceed predetermined thresholds. Also included under rental income are reimbursements for general property expenditures that WPG pays for all tenants, such as utility, security, janitorial, and other administrative expenses, as well as real estate taxes and insurance. Only a fixed portion of these expenses was reimbursed. On average, rental income accounted for ~95-96% of WPG’s annual revenue. The remainder comes from ancillary programs, such as holiday events, sponsored children’s play areas, and local promotions, joint venture fee income, and insurance proceeds [1] [4].

WPG’s primary costs are property operating expenses and reinvestment costs. Property operating expenses are the expenses associated with operating WPG’s properties (e.g. utilities, security, etc.). As discussed above, these expenses are partially reimbursed by tenants. Thanks to these reimbursements, WPG maintained a high net operating income (NOI) margin in the high 60s. NOI is a metric REITs use to measure property-level operating earnings, and roughly equals rental income less property operating expenses (property taxes, insurance, utilities, repairs, management, ground rent), excluding corporate SG&A, interest expense, income taxes, and D&A. Reinvestment costs include maintenance costs to maintain and repair existing properties, investments to improve the productivity of occupied properties and acquire or develop new properties, and tenant allowances. Capex represented ~25-30% of annual revenue, which is quite significant and highlights WPG’s constant burden of maintaining and improving its properties [4].

Readers may wonder how a REIT can spend ~25-30% of revenue on capex yet still pay out 90%+ of its taxable income to investors. This is because taxable income is usually much lower than true cash flow because large non-cash depreciation (and other tax adjustments) reduces what is taxable, so the legal 90%+ dividend requirement typically doesn’t consume all available cash generated. In practice, REITs cover routine property spending with cash generated from operations and can retain up to 10% of taxable income each year; for bigger projects (redevelopment, new builds), they often use a mix of debt, asset sales/joint ventures, and, when attractive, new equity.

Events Leading up to Distress

Over the past two decades, the U.S. retail industry has undergone a significant transformation as consumer preferences have shifted away from brick-and-mortar stores toward online shopping. The expansion of broadband access in the 2000s, coupled with improvements in digital payments and logistics, allowed e-commerce platforms such as Amazon and eBay to expand beyond niche categories. This marked the beginning of a sustained change in how consumers shopped for both discretionary and everyday goods [2].

By the mid-2010s, the pace of this transition accelerated. From 2010 to 2018, U.S. brick-and-mortar retail sales grew at a CAGR of 4%, but e-commerce expanded much faster at a CAGR of ~15%. Online sales as a share of total retail doubled to 10% by 2018, and this rapid growth left many physical stores with stagnant or declining sales [7] [8]. The challenges were especially acute for department stores and mid-tier mall tenants that relied heavily on in-person traffic. Beginning in 2015, the U.S. experienced thousands of store closures, a trend that is now commonly referred to as the “retail apocalypse.” In 2019 alone, U.S. retailers announced more than 9,300 store closures, or ~1% of total physical stores [9].

The slow death of the traditional retail model was a major threat to WPG. E-commerce sales as a percent of total retail sales would only continue to climb over time (to ~12% in 2019), while revenues of large shopping centers declined by an average of 0.8% from 2012 to 2017 [10].

As one might expect, these secular shifts created substantial headwinds for WPG’s operations. The rapid growth of e-commerce meant that certain of WPG’s tenants became unable to pay their rents, leading to store closures and higher rates of property vacancy, and in-turn lower average rent psf (more on these metrics later). In fact, certain of WPG’s tenants, such as Toys “R” Us, a major toy and clothing retailer, Bon-Ton Stores, a regional department store chain, and Sears, a national department store and big-box retailer, were forced to file for Chapter 11 across 2017 and 2018 due to these macroeconomic pressures. Notably, WPG’s properties housed 35 Sears stores across ~5mm of gross leasing area (8% of WPG’s total 2018 GLA) [2] [5].

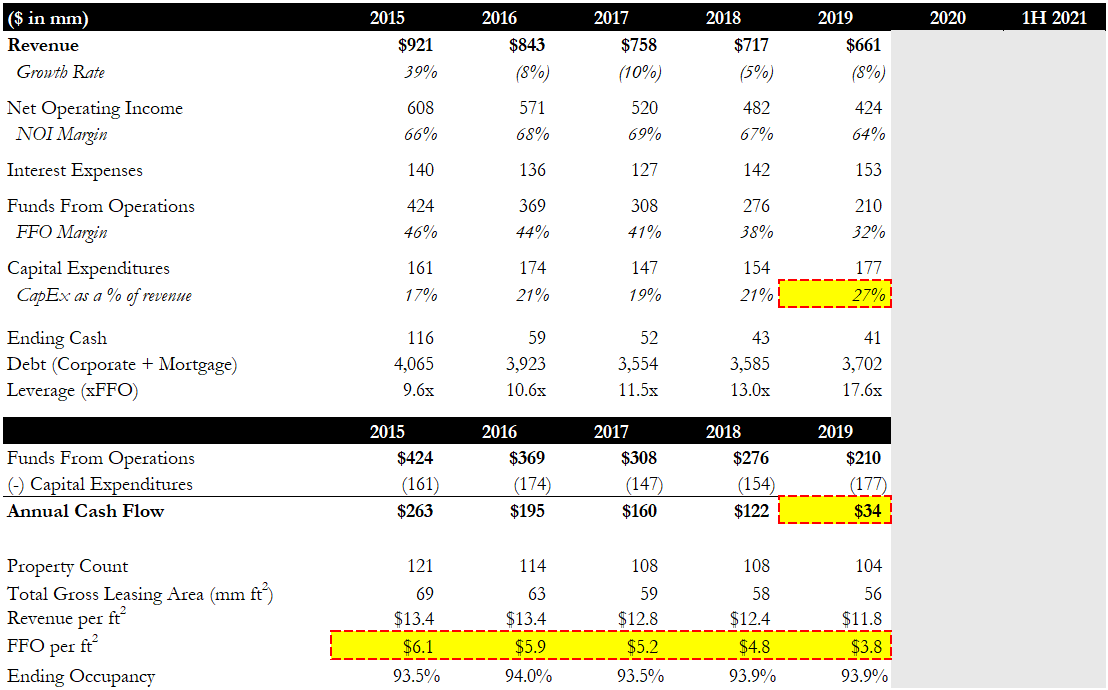

Not only did these bankruptcies lead to vacancies in WPG’s properties, and in-turn lost rent, they also resulted in higher costs to attract new tenants. This is because WPG typically had to offer much larger tenant allowances for new leases than for simple renewals. For example, across 2017 and 2018 the company averaged $33.8 psf in allowances on new leases. Average starting base rents on new leases across the same period were roughly $24 psf, meaning the upfront cash outlay to re-tenant a vacant space exceeded a full year of base rent by nearly 30% [5]. In other words, each bankruptcy-induced vacancy not only reduced income but also required meaningful new investment to refill the space. Figure 3 details WPG’s financials from 2015 to 2019.

Figure 3: Prepetition financials, 2015 – 2019 [5]

Note that instead of adjusted EBITDA, we use funds from operations (FFO) as a rough proxy for cash flow. FFO is a REIT-specific profitability metric that provides a standardized view of recurring operating performance that starts with net income, adds back real estate depreciation, excludes gains on property sales, and adjusts for other non-recurring expenses, thereby approximating ongoing cash-generating capacity under real estate accounting conventions. Since interest expense is already deducted from FFO, annual cash flow is estimated by simply deducting capex from FFO.

From 2015 to 2019, WPG’s performance deteriorated across both revenue and operating efficiency. Revenue fell, driven by asset sales that reduced total gross leasable area, weak results from joint venture properties, and worsening performance at comparable centers following major anchor tenant bankruptcies. These bankruptcies not only reduced rent from vacated space but also raised the cost of backfilling that space, since WPG had to offer new tenants larger upfront allowances. The combined effect shows up in WPG’s FFO per square foot (FFO divided by total gross leasable area), which reflects occupancy, rent levels, collections, and operating efficiency while controlling for changes in portfolio size. Over this period, FFO per square foot fell by nearly 40%, from $6.1 to $3.8, indicating that WPG was not only shrinking but also generating less cash flow per unit of space.

To make matters worse, WPG’s main cash outflow, capex (primarily maintenance, as the company was generally downsizing and not making significant acquisitions of new properties) stayed flat progressively making up a percentage of revenue given the ongoing decline (capex as a percentage of revenue peaked at 27% in 2019). In short, WPG was converting less of its declining revenues into profit, while simultaneously reinvesting more of that profit just to maintain operations. Annual cash flow nearly halved from $263mm in 2015 to $122mm in 2018, before falling to just $34mm in 2019.

WPG’s balance sheet was also worrisome. From 2015 to 2019, total debt decreased slightly from $4.1bn to $3.7bn while cash remained low, hovering between $50–$100mm. Leverage, measured as total debt to FFO, climbed from under 10x to nearly 18x. Industry average for equity REITs at the time was ~8-10x. In effect, WPG became increasingly levered relative to its shrinking size, while growing less profitable overall. This is likely because the company was using proceeds from its divestitures to fund debt repayments, but divested these assets at low valuations, which pushed overall leverage up (WPG received less for its assets relative to the profits that they contributed). WPG’s valuation suffered accordingly – market cap fell from a peak of $3.2bn in February 2015 to $680mm by the end of 2019 [11].

COVID Pandemic

Given WPG’s deteriorating financial position going into 2020 and the headwinds facing the brick-and-mortar retail industry, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 was the nail in the coffin. The company had $3.1bn in total debt and $160mm in liquidity ($40mm of cash and $120mm of revolver capacity) at the end of Q1 2020 [5].

Beginning in Q2 2020, all of WPG’s properties faced temporary government-mandated closures, reduced operations, and/or other operational restrictions. This resulted in reductions in the operations of WPG’s tenants, and therefore reductions in WPG’s revenues [2]. While lease agreements generally obligate tenants to pay rent even during closures, many retailers withheld payments or sought abatements and deferrals during the pandemic. Tenants often pointed to “force majeure” clauses, which excuse performance of obligations during extraordinary events such as government shutdowns. However, in most mall leases, these provisions apply only to non-monetary obligations, such as operating hours, and specifically carve out rent, meaning rent is still legally due [12].

Despite this, enforcement was difficult, so in an effort to maintain tenant relationships, WPG turned to negotiating with certain tenants to grant relief through rent deferrals and abatements. In practice, this meant some tenants were allowed to postpone payments to a later date (deferral), while others received temporary reductions or complete rent forgiveness for a limited period (abatement) [2]. As a result, WPG’s rent collection rate, the percentage of rent that it actually received from tenants compared to the total rent it billed, fell to just 52% in Q2 2020, before partially recovering to 87% in Q3. Healthy REITs under normal economic conditions average collection rates of 98-100% [13].

By the end of 2020, all of WPG’s shopping centers were open again; however, they experienced significantly lower foot traffic due to uncertainty caused by the pandemic. Additionally, many of WPG’s tenants were still unable to meet their lease obligations, resulting in the aforementioned lease reliefs or premature lease terminations. Certain of WPG’s tenants, such as retailers J.C. Penney and Ascena Retail Group (parent of Ann Taylor, a women’s clothing retailer), filed for Chapter 11 themselves, leading to widespread store closures and vacancies across WPG’s locations [2] [13].

Furthermore, recall that WPG’s rent agreements were structured as either fixed minimum payments plus overage rents based on sales performance or percentage arrangements that are tied directly to tenant sales. This means that not only was WPG not earning its fixed rental payments, it was also entirely losing out on sales-based rental income under both types of contracts. Even when stores slowly reopened, significantly lower retail foot traffic driven by government restrictions and concerns surrounding the pandemic dampened WPG’s sales-based rental income.

All of these developments resulted in rental income decreasing by $127mm year-over-year, $24mm of which can be attributed to rent reliefs granted to tenants. WPG also booked a $52mm downward adjustment related to the future collectability of rents (for context, 2020 revenue was $524mm) [2] [4].

Financial Responses

In response to the pandemic, throughout 2020, WPG took a number of measures to preserve liquidity.

You are about to reach the midpoint of the report. This is where the story gets interesting.

Upgrade to Pari Passu Premium to access the remainder of this deep-dive, the full archive with over 150 editions, and our restructuring drive.

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Full Access to Over 300,000 Words of Evergreen Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Access to the Restructuring Drive