Welcome to the 130th Pari Passu newsletter.

Today’s retail landscape looks vastly different from even 10 years ago. Online retailers have experienced immense success, compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, while traditional brick-and-mortar retailers have struggled to adapt. Because of this, we’ve seen a number of high-profile retailers, such as Party City, Forever 21, Joann Fabrics, and Rue21, restructure within the past couple of years.

One of the largest burdens for struggling retailers is the rent expense for leased store locations. While getting out of leases can be tough, Section 365 of the Bankruptcy Code provides debtors with the flexibility to manage their executory contracts and unexpired leases effectively. This write-up will dive into some important considerations under Section 365 and highlight its importance during retail bankruptcies, using the recent Express, Inc. Chapter 11 as an example of its significance.

Importance of Section 365 in Retail Bankruptcies

A common theme among recent retail bankruptcies, including those listed above, is reduced storefront foot traffic due to consumers moving online. Facing declining revenues and large fixed rent payments, Chapter 11 bankruptcy provides a much-needed out for retailers.

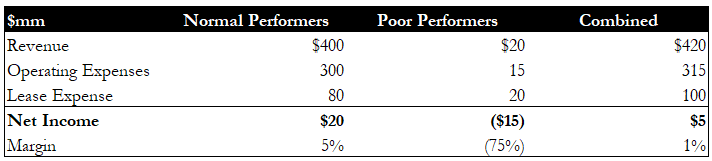

Section 365 allows retailers to reject leases for unprofitable locations while assuming or assigning leases for high-performing ones. To put some numbers to an example, imagine Retailer ABC operates 250 leased stores. Each store pays $400,000 in rent expense. Other operating expenses are 75% of revenue. Assume 50 stores are extremely poor performers, earning $400,000 in revenue annually. In contrast, the other 200 earn $2mm. Retailer ABC’s financial profile is reflected below.

Figure 1: Retailer ABC’s Financials by Store Category

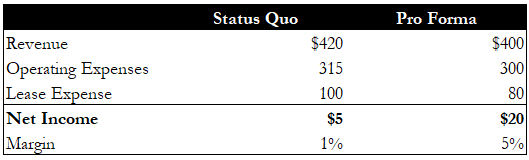

After experiencing some vendor troubles and severe cash burn, Retailer ABC files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Under Section 365, the debtor chooses to reject the leases for the underperforming stores and close them. On a per-store basis, the underperformers are losing $300,000 each year (-$15mm/50). For every underperforming lease that Retailer ABC rejects, it can increase net income by $300,000. Assuming they shutter all 50 underperformers, on a pro forma basis, annual revenue would be $400mm with net income of $20mm, saving the retailer $15mm per year. The rejections increased the net margin from 1% to 5%. While a very simplified example, this shows the impact of rejecting leases and optimizing store footprint on a retailer’s bottom line. Additionally, a sale of the business now becomes much more attractive to debtors, as we’ll see with Express.

Figure 2: Retailer ABC’s Pro Forma Financials

Executory Contracts

While not explicitly defined under section 365 of the bankruptcy code, an executory contract is an ongoing legal agreement where both parties still have obligations to fulfill. Courts often rely on the “Countryman” test to determine if a contract is executory. The Countryman definition outlines two conditions that make a contract executory. First, both parties still have obligations to perform. Second, failure to perform these obligations would result in a material breach – a contract violation that gives the non-breaching party the right to seek damages or contract termination. While some courts have been moving away from the Countryman definition, it remains a baseline test for determining whether or not a contract is executory [2].

Let’s test some examples under this definition:

A fast food franchisor enters franchise agreements with various fast food franchisees. Under the agreement, the franchisor provides its trademarks, systems, and support, while the franchisee pays a fee and must adhere to specific standards. Because both parties have ongoing obligations, this contract would be considered executory.

An educational institution enters a 3-year service agreement with an IT firm to provide ongoing tech support and cybersecurity services. In exchange, the company pays monthly fees to the IT firm. This service agreement would be considered an executory contract.

A retailer enters a supply contract with a widget manufacturer. Prior to filing, the manufacturer delivers the amount of widgets outlined under the agreement, but the retailer has yet to pay the manufacturer. This contract is not executory because the manufacturer has already fulfilled its obligations. Instead, the money owed to the manufacturer would likely be treated as an unsecured debt claim.

A lender provides the debtor with a promissory note, where the debtor's only obligation is to repay principal and interest would not be considered an executory contract.

Many executory contracts are crucial to a business’s operations, and their treatment in bankruptcy is critical to ensuring the stability of the reorganized entity.

Unexpired Leases

Unexpired leases are lease agreements for real or personal property that remain in effect at the filing date and are treated similarly to executory contracts under the Bankruptcy Code. To quickly define real vs. personal property, real property includes land and anything permanently attached to it, such as buildings, fixtures, etc. Personal property, such as vehicles and equipment, is movable and not connected to land. Some common examples of unexpired leases include retail leases of mall space, corporate office leases, and lease agreements for fleets of company vehicles. For companies that rely heavily on leased assets, such as retailers, rent payments for unexpired leases may be more burdensome than interest on debt, so restructuring lease obligations is just as important as treating debt.

Treatment Under Section 365

Section 365 of the Bankruptcy Code outlines the treatment of executory contracts and unexpired leases. Importantly, it gives the debtors the power to assume, reject, or assign leases. Let’s summarize what each of these options entails under Section 365:

Assumption: The debtor commits to fulfilling the contract or keeping the lease post-bankruptcy. This is often seen with leases for favorable locations or agreements at favorable terms to the debtor, which they may not want to reject. In order to assume a contract or lease, the debtor must satisfy a couple of conditions. First, the debtor must cure any defaults, such as overdue payments, and cover any other associated damages. Additionally, the debtor must assure future performance, such as showing improved cash flows post-reorganization, at a rate sufficient to cover the lease obligations on a go-forward basis [1].

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Get Access to the Restructuring Drive

- See Sources and Backups to All Free Writeups

- Join Hundreds of Readers