Welcome to the 66th Pari Passu newsletter.

A few weeks ago, we covered the ongoing restructuring of Lumen. Today, we are back with another asset-heavy restructuring lesson: the Spanish steel manufacturer Celsa.

On the 4th of September 2023, Spanish judges ruled that ownership of the company would be transferred to creditors, ending a drawn-out three-year battle.

But what is Celsa? And how did they end up giving the keys to creditors? Why should we care? To understand the intricate workings of one of Europe’s most high-profile restructurings in the past decade, we must first learn more about the company at the center of this dispute.

Part 1: A Deep Dive into the 2023 Restructuring

Company Overview

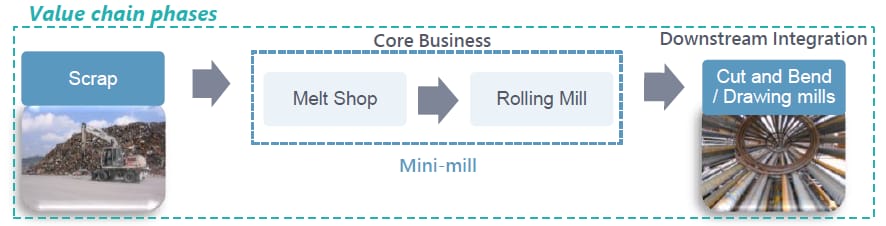

Headquartered in Castellbisbal, Spain, Celsa Group is one of the largest long steelmakers in Europe. It is the 1st producer of corrugated products, the 2nd producer of profiles and bars, and the 3rd high-end wire rod producer in Europe. The Company, formerly privately owned by the Rubiralta family, operates in Spain, in France, the UK, Poland, and the Nordics. The Company uses Electric Arc Furnace technology in its processes, and it is present across the entire steel value chain including scrap, melt shops, rolling mills, and cut and bend. Celsa mainly serves the Construction and Automotive industries, but also the Agriculture, Oil & Gas, and Energy industries.

How did we end up here?

Over the last ten years, they underwent two restructurings, one in 2013 and one more recently in 2023. Back in 2013, Celsa was badly affected by poor economic conditions in Spain, and ended up refinancing €2.5bn of debt through a “Spanish Scheme” process, with 91% of lenders supporting the deal [1]. At the time, most creditors were banks such as Barclays and Santander [2], but this would greatly change in 2020, as almost all of them needed to sell their positions at significant discounts upon the distressed situation arose. Celsa’s operating subsidiaries across Europe have also undergone major refinancings, with Celsa Huta, their Polish subsidiary, refinancing Z2.3bn ($634mm) of debt into two new facilities [3].

What happened in 2013?

The “Spanish Scheme” was a restructuring process introduced in 2011 by legislators. It was initially regarded as helpful to struggling businesses wanting to pursue out-of-court solutions, but then opinion quickly changed and the Scheme was later criticized for being too rigid. In particular, the scheme was tilted in favor of secured lenders who could enforce their debt claims in almost all cases making companies with significant secured debt harder to restructure. In the case of Celsa in 2013, the company decided to use the Scheme to cram down on 9% of secured creditors who were opposing the scheme. Courts ended up approving this, stating that the opposing creditors’ secured debt was actually unsecured. The decision ended up coming down to a one-word difference, with the judge stating that creditors were “formally” but not “materially” secured, meaning that they couldn’t enforce their security and claim Celsa assets in the event of a default and were thus unsecured.

Another point of clash in the process was the extension Celsa would receive on the terms of the debt, which the courts set at 5 years while the Spanish Insolvency Act had set a maximum of 3 years. In response, judges clarified that the maximum term of 3 years set out by law only applied to how long lenders would have to wait before enforcing and collecting their debt claims from the company rather than giving the company a longer runway to repay the debt back, effectively allowing the company to retain the new 5 years maturity. What this meant for potential future creditors was that they had to keep a close eye out for judge decisions, especially their interpretation of the law and the implications for lender recoveries. [1]

What happened during the pandemic?

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals