Welcome to the 156th Pari Passu newsletter.

In today’s edition, we’re looking at off-balance sheet factoring facilities, a financing tool that has become one of the most controversial and misunderstood credit mechanisms. While traditionally used as a working-capital bridge, factoring has evolved into a complex form of financing, altering the perception of leverage.

If you read our newsletter, then chances are you’ve also seen the headlines around First Brands Group’s bankruptcy, which has been popularized not only by its $10bn+ of liabilities, but also its $2.3bn of factored receivables. Those receivables sit at the center of an investigation into First Brands, and may have a lasting impact on future factoring facilities.

This writeup breaks down how factoring works, how GAAP and bankruptcy law define a true sale of receivables, and why companies use factoring and off-balance sheet structures. We’ll use hypothetical examples to show how factoring can meet working capital needs, improve perceived liquidity, and complicate creditor recoveries. We’ll end with live updates on the First Brands situation, which tests nearly every concept covered in this piece.

Before we get started, we launched the first Restructuring Competition, learn more here.

When markets move, speed wins. 9fin helps you move faster.

9fin delivers the speed, depth and efficiency you need to stay ahead.

Here's how 9fin helps you move first:

Fastest alerts. Get real-time intelligence 30-60 minutes before traditional sources across leveraged finance, distressed debt, CLOs and private credit.

Complete coverage. Bonds, loans, public and private credit — seamlessly unified in one platform. Gain visibility in opaque segments where others go dark.

AI powered tools. Built by debt experts, for debt experts. Turn days of research into minutes, with every data point traceable to source.

Real time updates, editorial insights, and AI all connected — so your workflow just works. Thousands of leading professionals trust 9fin to move faster, act smarter, and win with confidence.

Ready to experience the intelligence advantage for yourself?

What’s more, we're offering qualified Pari Passu subscribers access to a 45 day free trial - 15 days longer than usual.

Or click here to learn more about 9fin and sample some of our latest coverage.

Factoring Overview

Factoring is a form of financing that allows companies to convert their accounts receivable into immediate cash. Traditionally, when a company sells goods or services, it issues an invoice to its customer, which is often not paid for thirty, sixty, or even ninety days. Instead of waiting for the cash payment, some companies opt to sell the invoice to a third party, known as a “factor”, at a discount, typically around 95 to 98% of the face value of the receivables (this discount represents the fee charged by the factor). Importantly, factors often won’t advance the entire cash balance upfront. Typically, 75% to 90% of the receivable’s face value is advanced upfront, and the remaining balance is transferred, less dilutive credits (as applicable) and the abovementioned discount, once customer accounts have been collected [1]. Dilutive credits refer to adjutments that reduce the collectible value of an invoice, such as returns or rebates. Therefore, once the customer has paid the invoice, the operating company will have collected the full receivables balance, less credits and the factoring fee. The Factor’s fee represents its earnings for providing upfront liquidity and assuming the risk that the customer may not pay on time, or at all.

To numerically illustrate concepts in this primer, we’ll use ABC Co. as a hypothetical example. First, imagine ABC Co. sells $100k worth of goods to a customer on sixty-day terms. Instead of waiting two months to collect, ABC Co. sells the invoice to Factor Co. On the day of the sale, Factor Co. advances 85% of the invoice, or $85,000, to ABC Co. When the customer eventually pays the full $100,000 on day 60, Factor Co. sends the remaining $15,000 back to ABC Co., but subtracts its $3,000 factoring fee. In total, ABC Co. has collected $97,000, with $85,000 upfront and $12,000 later, with the $3,000 difference in cash collected and face value representing the cost of accelerating cash flow.

Common Factoring Structures

Although the basic idea of factoring is simple, facilities can be structured in several different ways, depending on the borrower's needs and the factor’s risk tolerance:

Notification vs. Non-Notification:

First, a factoring arrangement can be a notification or non-notification agreement [1]. In a notification deal, the customer is explicitly informed that its invoice has been sold and is directed to pay the Factor rather than the operating entity. This makes receivable collection straightforward and reduces the risk of misdirected payments. In a non-notification deal, the customer is never told that the receivable has been factored and continues to pay the operating company as though nothing has changed. When customers pay the operating company, cash collected from factored invoices is typically held in segregated accounts before quickly being upstreamed to the factoring company. Tight cash management controls become extremely important down the line, when considering the accounting and legal treatment of factoring facilities. Non-notification structures are attractive to companies that want to keep their financing structures out of customer view, but they also expose the Factor to more risk since cash flows through the company before reaching them. Each structure carries its own benefits, and both are common, with notification factoring often being utilized by middle-market companies and non-notification being utilized by large or sponsor-backed companies.

Regular vs. Spot:

Factoring can also be arranged on a regular or “spot” basis [1]. In a spot deal, like the ABC Co. example above, the company and Factor agree on a one-off transaction, selling a single receivable or a small batch. This might be done to address a one-off short-term liquidity pinch. Companies might also use spot arrangements when confidentiality or customer relationships are a concern. For example, a company that is limited to a notification structure might only factor receivables of select customers. On the other hand, a regular factoring deal functions more like a revolving credit facility. The company and Factor will maintain an ongoing relationship and have an approved limit, which can be drawn and repaid. Regular factoring programs are more common among all types of companies, as they are cheaper and more easily integrated over the longer term. Conversely, spot factoring may be a viable option for small businesses that need immediate cash against specific invoices (e.g., a $100k sale to Walmart that won’t pay for 60+ days).

Recourse vs. Non-Recourse Factoring:

The last and most important distinction is whether the factoring agreement is recourse or non-recourse [1]. In a recourse arrangement, if the customer fails to pay the factor, the Factor may demand repayment from the operating company. Economically, that puts the customer’s credit risk back on the company, making the transaction seem more like an RCF or ABL facility. In contrast, the Factor bears this customer credit risk in a non-recourse deal, under which the Factor bears any loss from non-payment. Due to this shift in risk, non-recourse factoring arrangements almost always feature higher fees than recourse deals. Non-recourse deals are also much more likely to qualify as a “true sale”, which will become very important as we explain the implications of a true sale in a distressed context.

Accounting Treatment: On vs. Off Balance Sheet

Another important nuance of factoring facilities is how they show up in the financial statements. Since a company is “selling” its receivables, it initially makes sense that they should be derecognized (removed from the balance sheet). Under US GAAP, the Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) section 860 (Transfers and Servicing) governs the accounting treatment for transactions involving the transfer of financial assets, including factoring. Under ASC 860, three conditions must be met for the receivables to come off the balance sheet [2]. To eliminate any confusion, in the case of factoring, the transferor is the operating company, while the transferee is the factoring company.

Legal Isolation: “The transferred financial assets have been put presumptively beyond the reach of the transferor and its creditors, even in bankruptcy or other receivership.” This means the receivable must be legally separated so that even if the company files for Chapter 11, its creditors can not claim them.

Transferee’s Right to Pledge or Exchange: “Each transferee has the right to pledge or exchange the assets it received, and no condition both constrains the transferee from taking advantage of that right and provides more than a trivial benefit to the transferor.” This test ensures that the Factor truly controls the receivables and isn’t limited to acting as a collection agent. In practical terms, a factoring agent should not be prohibited from reselling receivables to anyone, even competitors. Any restrictions placed on the Factor should provide no more than a “trivial benefit” to the operating company. For example, if a Factor is required to notify the operating company when it sells factored receivables, this restriction may be considered a trivial benefit as it doesn’t really limit the factor’s control.

Surrender of Control: “The transferor does not maintain effective control over the transferred financial assets through (a) an agreement to repurchase or redeem them before maturity, or (b) the ability to cause the transferee to return specific assets.” This means the company can’t have any mechanism to call back or reclaim the receivables.

Under GAAP, if these three criteria are met, the factoring is treated as a true sale, and the receivable is removed from the balance sheet, and no liability is recorded. If any three of the criteria are not met, the factoring is treated as a secured borrowing on the financial statements, meaning the factored receivable remains on the balance sheet at 100% of face value, and the company records a liability for the cash advance. Once the customer pays the factor, the receivables and associated liability come off the balance sheet. Let’s return to ABC Co. for a quick example.

Consider two scenarios, in both of which ABC Co. once again sells its $100,000 invoice to Factor Co. on sixty-day terms at an 85% advance rate and 3% factoring fee. In the first scenario, the deal is structured as non-recourse, and Factor Co. assumes the risk of collection. The receivables are legally isolated in a separate SPV so ABC Co.'s creditors could not reach them (legal isolation). Factor Co. also obtains unrestricted rights to collect, pledge, or exchange the receivables (right to pledge or exchange). Lastly, ABC Co. has no contractual right or obligation to repurchase or substitute any receivables (surrender of control). In this case, ABC. Co.’s transfer of receivables to Factor Co. passes all three GAAP tests and thus is considered a true sale. Therefore, the receivables can be derecognized from the balance sheet.

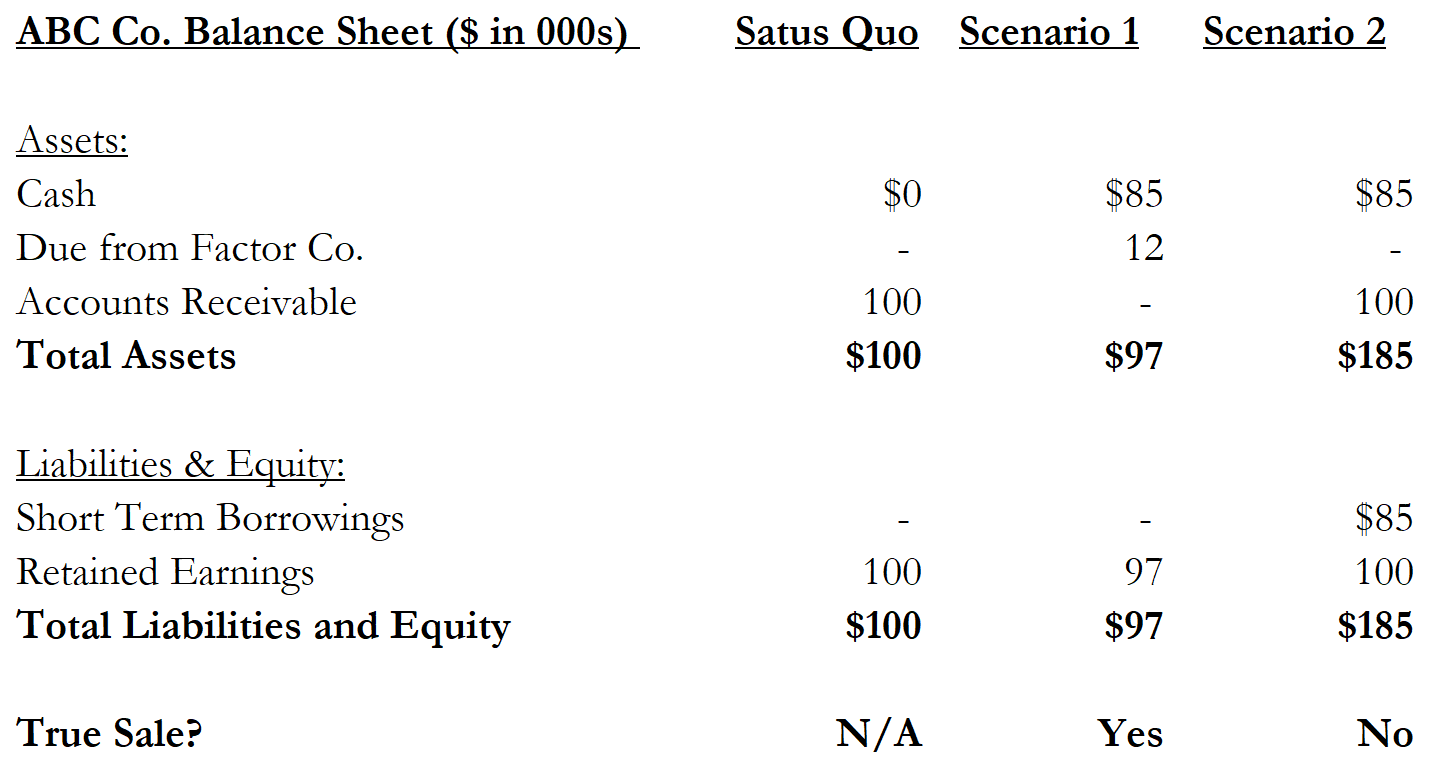

In the second scenario, assume the factoring arrangement is exactly the same, but this time it includes recourse. If customers fail to pay, ABC Co. must reimburse Factor Co. for any losses or substitute the delinquent receivables with new ones. Even though the receivables are legally isolated from ABC Co., and Factor Co. obtains the right to exchange or pledge, ABC Co. has retained effective control through its obligation to substitute or repurchase. In this case, since ABC Co. hasn’t fully surrendered control, the third criterion for derecognization has not been met, and the transaction is not considered a true sale. Therefore, ABC Co. must record a short-term liability secured by its receivables, which remain on the balance sheet. The figure below summarizes the balance sheet under each scenario:

Figure 1: ABC Co. Balance Sheet Immediately Following Factoring Transaction

A couple of notes on the image above:

First, the “due from factor” arises in scenario one as ABC Co. is still entitled to funds remitted from Factor Co. following payment from the customer. Importantly, this represents ABC Co.’s residual interest in the transaction, not continued ownership or control of the receivables themselves. Under ASC 860, this due from Factor is treated much like a short-term receivable, as it represents cash that is almost certain to be collected within a few months (unless Factor Co. defaults). On the other hand, in scenario 2, no due from Factor is recorded because, in GAAP terms, the receivables remain on ABC Co’s books as its own asset, and customer payments in excess of the cash advance and fee flow straight to ABC Co’s books rather than being routed through a Factor.

Second, note how the leverage profile looks completely different in each case. In Scenario 1 (true sale), the company has no debt on its balance sheet, and reported leverage is effectively zero. In Scenario 2 (secured borrowing), leverage equals 85% of the receivables’ face value, mirroring the advance rate, which materially alters the company’s debt position.

In summary, two transactions with identical cash economics can produce dramatically different financial statements. The GAAP treatment of factoring facilities becomes crucial for a company’s true liquidity position and leverage profile.

Reasons for Factoring

To understand why companies use factoring facilities, we’ll return to ABC Co., covering two primary use cases.

The first and more intuitive use case is working capital management. Imagine that ABC Co. is a middle-market supplier of specialty cleaning products, selling primarily into big box retail, with Walmart accounting for more than 50% of its sales. Like most large retailers, Walmart is able to leverage its scale and bargaining power to negotiate extended payment terms, often 90 days, leaving smaller vendors like ABC Co. waiting for months to collect cash. On the other hand, ABC Co. must pay its own suppliers within 30 days and cover payroll every two weeks. The result is cash flowing out faster than it comes in. By factoring its receivables, ABC Co. is able to accelerate cash receipts from its invoices upfront to cover current working capital needs.

Why doesn’t ABC Co. just borrow on a revolving line of credit? The second use case relates to a company’s leverage optics. Even when a company has adequate liquidity, the accounting treatment of factoring can make it an appealing tool for managing leverage-related metrics. The clearest example of this is net debt-to-EBITDA. In a true sale arrangement, cash is received, but there is no corresponding liability recorded, representing a dollar-for-dollar decrease in net leverage and no change in total leverage. This creates a rare and interesting dynamic where a company can raise liquidity while simultaneously lowering reported net leverage, as the cash inflow from factoring is essentially treated as a cash flow from operations rather than financing. On the other hand, if the company were to borrow via an RCF, cash would increase, but so would debt, leaving net debt the same and increasing total debt.

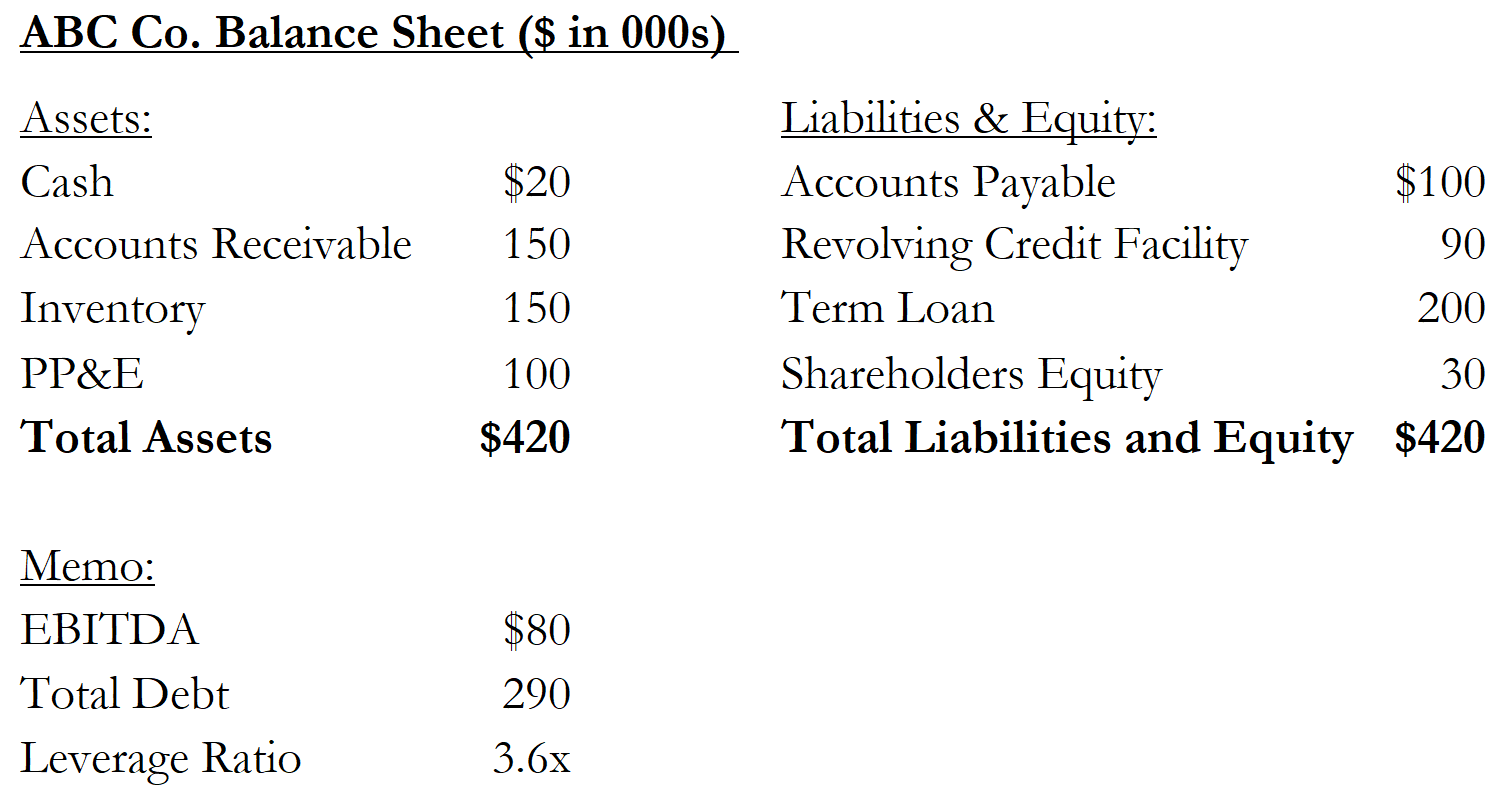

To illustrate this dynamic, imagine ABC Co. now has a balance sheet with $150mm of outstanding receivables and a covenant limiting total debt to EBITDA of 4x. The company is facing a short-term working capital squeeze following a seasonal inventory build and delayed collections from its Walmart. To fund operations, management considers two options: drawing $30mm on its revolving credit facility or factoring $30mm of receivables under a non-recourse true-sale arrangement. ABC Co.’s pre-transaction balance sheet is presented below:

Figure 2: ABC Co.’s Pre-Transaction Balance Sheet

With $290mm of total debt, representing 3.6x EBITDA, ABC Co. sits just below its 4.0x maximum covenant threshold. With only $20mm of cash on hand, the company expects a temporary working-capital shortfall, as payables come due before collections from its major retail customers.

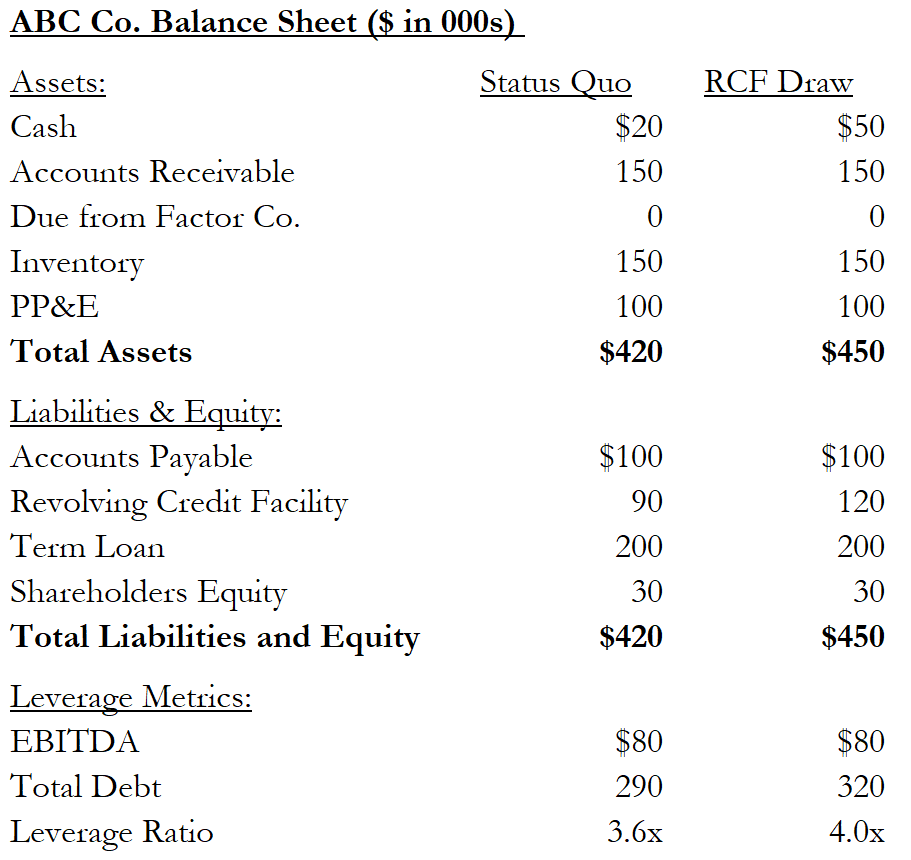

Figure 3: ABC Co. Balance Sheet with RCF

Under the first option, which is detailed above, ABC Co. draws $30mm from its revolver to fund payables. While this immediately increases cash, it also raises total debt to $320mm, pushing leverage to its maximum limit of 4.0x. Any additional borrowing or decline in EBITDA would push leverage above its limit. While an RCF draw solves ABC Co.’s liquidity problem, it presents the new issue of lender scrutiny.

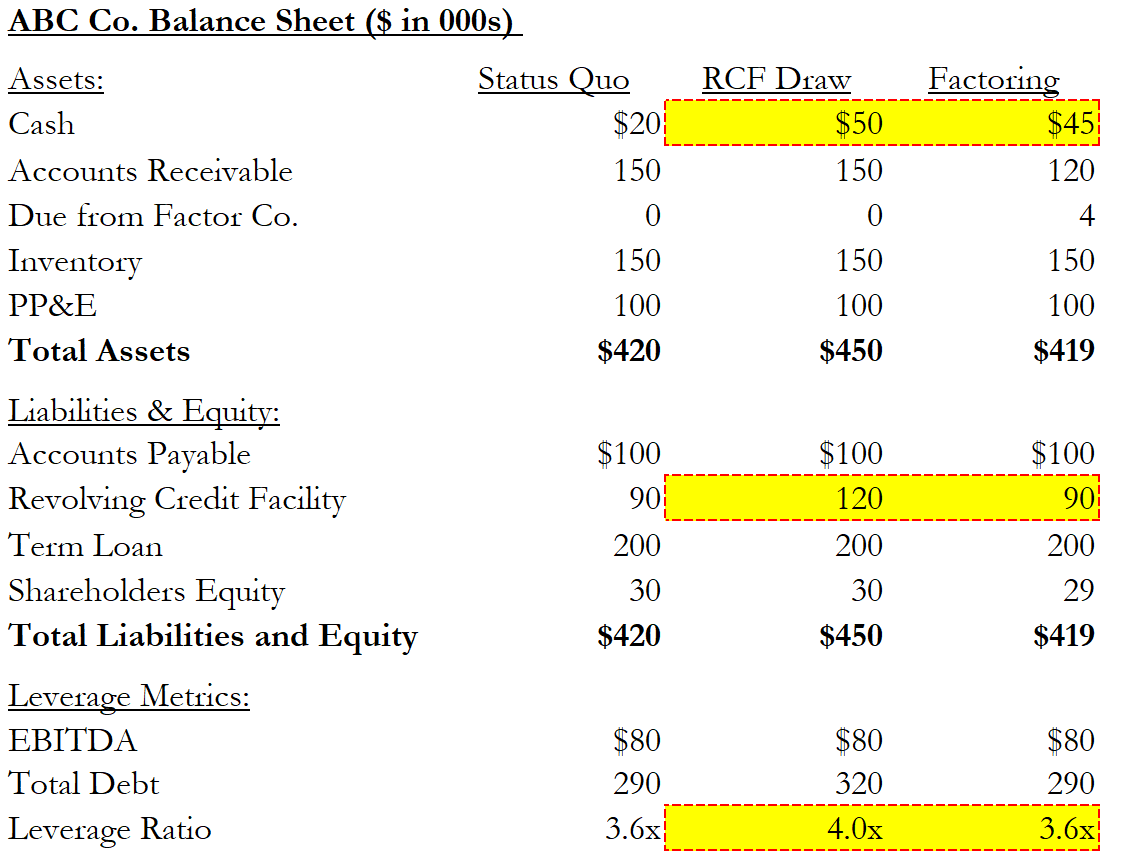

Figure 4: ABC Co. Balance Sheet with Factoring

Under the second option, which is also detailed above, ABC Co. instead factors $30mm of receivables under a non-recourse arrangement. Since the transfer qualifies as a true sale, the receivables are derecognized from the balance sheet. ABC Co. also records a $4mm due from Factor and $1mm loss on sale, recognizing the advance rate and factoring fees, respectively. Assuming a 90-day payment cycle, this represents an annualized Factoring cost of nearly 14% (1.033^4 - 1). Thus, a factoring arrangement is more expensive than an RCF draw, which would likely carry an all-in rate of 8-9% (SOFR + 3.00 / 4.00%), in today’s rate environment. This increased cost represents the transfer of risk from the operating company to the Factor. Importantly, under this arrangement, total debt remains unchanged, and ABC Co. remains at 3.6x leverage, despite having raised $25mm of immediate cash.

Transactions like this highlight why factoring serves as both a viable funding and financial reporting strategy. By accelerating the conversion of receivables into cash without recording additional debt, companies can present a stronger liquidity position and lower leverage. However, when factoring is used too aggressively, it can mask excessive underlying leverage or recurring cash shortfalls.

Factoring via Special Purpose Vehicles

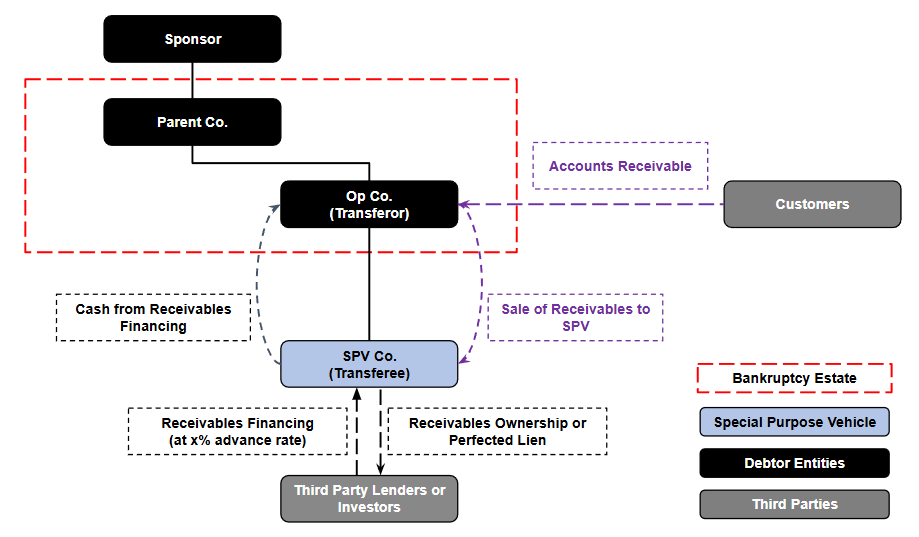

In practice, factoring doesn’t always involve a company selling receivables directly to a third-party finance company, especially for large or sponsor-backed companies. Instead, companies use SPVs to replicate the same economics and off-balance sheet treatment as traditional factoring.

In a typical SPV factoring facility, the operating company first sells a pool of accounts receivable to a newly created SPV, usually a wholly owned subsidiary, with the Parent Co. still owning 100% of equity. The SPV has no other business operations, existing solely to purchase, hold, and finance receivables. Because it's a separate legal entity, often with independent directors, it is designed to be bankruptcy remote, achieving legal isolation.

Importantly, these structures also rely on strict cash controls to preserve isolation. Customer payments are typically routed into controlled collection accounts held in the SPV’s name, rather than normal operating accounts. This prevents the operating company from commingling cash that technically belongs to the SPV. IF the parent were to collect into its own operating account first, it could blur the line of ownership and isolation. These segregated accounts may take multiple forms, each with varying risk profiles for the SPV/Factor. Here are some examples (from least to most risky) [10]:

Fully segregated account in the name of the SPV/Factor

Fully segregated account in the name of the operating company, but the SPV/Factor has continuous control or dominion

A collection account that the operating company fully controls

Simultaneously, the SPV finances this purchase by selling undivided ownership interest (meaning investors don’t own specific identifiable receivables, but instead own a proportional slice of the entire pool) in the receivables pool or by borrowing against them. In practice, this financing is often structured as short-term notes backed by the expected cash collections on those receivables. Regardless of the financing method, they remain off the operating company's balance sheet. The SPV then transfers financing proceeds directly to the operating company, providing the same accelerated cash advance as traditional factoring with a third party.

Figure 5: Example SPV Factoring Structure

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Full Access to Over 300,000 Words of Evergreen Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Access to the Restructuring Drive