Welcome to the 115th Pari Passu newsletter.

Over the last few months, we covered some landmark restructuring transactions including Red Lobster, Rite Aid, SunPower, and Hertz. Today, we are back with another all-time restructuring: The Neiman Marcus Group, Inc (NMG).

With roots tracing back to 1907 in Dallas Texas, Neiman Marcus is a luxury fashion retailer primarily operating brick-and-mortar retail shops. The business traded hands several times, first acquired in 1969 by retailer Carter Hawley Hale, then spun-off in 1987 before being bought out by Warburg Pincus and TPG in October 2005. Eight years later, in October 2013, Neiman traded hands among PE sponsors and was bought out a second time by Ares and the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB).

It was with this latter sponsor group that Neiman gained prominence in the restructuring world. Utilizing a controversial drop-down maneuver facilitated by loose credit documents, Neiman shifted their valuable MyTheresa asset outside the “credit box”—to the benefit of their PE sponsors and detriment of creditors. By 2020, NMG dropped into bankruptcy court with a COVID-driven Chapter 11 with fraudulent transfer claims at their heels.

From some hot-potato PE and a contentious drop-down LME, to a COVID-driven luxury retail bankruptcy, and criminal-bid-rigging charges, the drama of Neiman’s restructuring is unmatched, with implications reverberating throughout the restructuring arena.

But first, a message from our sponsor:

But first, a Resource Brought to You by Cognitive Credit

Over the past few years, we've spoken with senior management at more than 300 global asset managers and hedge funds across Europe and the US.

It's clear that many organizations are still uncertain how emerging technology fits into their traditional credit research process. But, as AI rapidly advances, credit investors who fail to leverage its potential will find themselves struggling to compete with their more agile peers.

Based on those conversations, our latest white paper spotlights how the credit market is leveraging technology and automation to unlock greater performance. Chapters include:

Credit data operations checklist to benchmark your practices

Advantages of implementing a credit data strategy

Initial requirements for a successful implementation

Examples showcasing current best-in-class

Who are we? Cognitive Credit - the market's premier provider of fundamental credit data and analytics for credit investors. Pari Passu subscribers can download a free copy!

Table of Contents

Company Overview: Origins of Neiman

“Neiman Marcus is Texas with a French accent” — Vogue, November 15, 1953, “Continental Chic in Texas” [16]

Founded in 1907 in Dallas, Texas by Herbert Marcus, Sr., his sister, Carrie Marcus Neiman, and her husband A.L. Neiman, Neiman Marcus is a leading luxury fashion retailer historically focused on brick-and-mortar shops. Boasting vendor arrangements with luxury brands including Chanel, Prada, and Gucci, Neiman operates by procuring and marketing inventory through their luxury storefronts, earning a margin on the goods. In 2018—the last disclosed annual financials before bankruptcy—Neiman saw $4.9bn of sales, $358mm EBITDA (7.3% margin), and $251mm of adjusted net income (5.1% margin). As evidenced by slim margins, the luxury retail industry is a competitive one, primarily competing on supplier relationships and inventory management. [1][16][BBG Terminal]

Prior to their 2020 bankruptcy, Neiman maintained over 5.1 million gross square feet of store operations in the U.S. By 2013, Neiman operated 43 Neiman Marcus stores (luxury retail), two Bergdorf Goodman stores (very luxury retail), and 24 smaller Last Call stores (“price-sensitive” luxury). [16]

As mentioned, Neiman Marcus has traded hands several times throughout its history. In 1969, it was acquired by Broadway-Hale for $40mm. In 1971, Broadway-Hale, later renamed Carter Hawley Hale, also acquired Bergdorf Goodman Company, one of New York City’s most respected retailers. Defending against a 1984 takeover attempt by borrowing $470mm to repurchase 51% of shares on open market landed Carter Hawley in deep waters, and by 1987, the struggling parent spun off Neiman Marcus, Bergdorf Goodman, and Contempo Casuals to form Neiman Marcus Group (NMG). By 1991, during the collapse of Milken’s junk bond market, Carter Hawley filed for Chapter 11 on February 11th 1991. It was eventually acquired in 1995 by Federated Department Stores, a predecessor to Macy’s, Inc., for $1.6bn. [17]

After several successful years of growth, NMG was bought out by Warburg Pincus and TPG in October 2005. The retailer again found itself a LBO target in October 2013, where it traded hands to Ares and the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB).

One of the crucial considerations of the Neiman restructuring was its enormous leverage, which was the result of these two LBOs. Thus, before we dive into the main focus of this article—Neiman’s infamous drop-down of MyTheresa, it is worth taking a look at the preceding LBOs.

2005 LBO (ft. Warburg Pincus and TPG)

Following economic recovery from the dot-com bubble burst, by 2005, LBOs were back in fashion and Neiman was the star of the runway.

With many eyeing e-commerce opportunities in luxury retail, Neiman attracted the interest of several PE firms. In FY2005, the retailer was generating steadily growing revenues of ~$3.8bn, with 35% gross margin, 11% operating margin, and 6.5% net margin. Earnings totalled ~$250mm. With $2.7bn of total assets, $854mm of cash and equivalents, $457mm of long-term liabilities, and net interest expense of ~$12mm pre-LBO, Neiman’s balance sheets were relatively healthy.

In the five fiscal years leading up to 2005, Neiman’s main segment Specialty Retail Stores (81% sales) grew at a 4.9% CAGR. From 1995-2005, the full-line Neiman Marcus and Bergdorf Goodman store count ballooned from 28 to 37 stores. By 2005, Neiman operated 35 Neiman Marcus stores, two Bergdorf Goodman stores, and 17 clearance centers. [18]

NMG had ambitious plans of future growth, with intentions to open a new Neiman Marcus store in San Antonio in September 2005, another in Boca Raton in November 2005, two more in Charlotte and Austin in 2007, another two in suburban Boston and Long Island in 2008, and another in greater Los Angeles area in 2009. Even before PE sponsors got involved, Neiman had planned a ~13% increase in square footage by 2009. Capital expenditures pre-LBO were ~$200mm. [18]

On May 2nd 2005, Warburg Pincus and TPG announced intentions to acquire the growing NMG. The sponsors would acquire all outstanding Class A and Class B shares of NMG through a reverse subsidiary merger—the sponsor-owned merger subsidiary will merge with NMG, the latter of which would be the surviving corporation—for $100 per share in cash, representing a transaction value of ~$5bn. The deal closed October 7th 2005, with each sponsor owning equal stakes upon close. [18][BBG Terminal]

The equity portion of financing consisted of $1.55bn, split equally among TPG and Warburg Pincus. Debt to capital ratio was ~70%. While the median deal comp multiples made this transaction look reasonable—median 1.82x TV/Revenue compared to NMG 1.31x; median 13.49x TV/EBIT compared to NMG 13.23x; median 9.33x TV/EBITDA compared to NMG 9.47x—it is interesting to note that deal comps included Toys R Us and Intelstat, and we know how that went…

So, how did the LBO change Neiman’s capital structure? Well, prior to LBO, NMG had a $350mm undrawn revolver, $125mm of 6.65% senior notes due 2008, and $125mm of 7.125% senior unsecured debentures due 2028. Thus, prior to LBO, Neiman had ~$250mm long-term debt. With $12.4mm interest in 2005, this amounted to an effective interest rate of ~5%. [18]

Post-LBO, NMG’s leverage increased by over 13 times (by their second LBO, it would be over 20 times their pre-LBO leverage). The 2008 notes were redeemed, and 2028 notes remained. Total existing and new debt outstanding post-LBO was ~$3.3bn, consisting of term and bridge loan facilities and 2008 senior secured. This number does not include an additional $600mm senior secured asset-based revolving facility. On a 2005 adjusted EBITDA of $528.4mm, this represents 6.25x leverage. Annual interest ballooned from $19mm to $217mm; with pre-LBO net income of only ~$250mm, Neiman was running tight. By 2006, net income had dwindled to $71mm, primarily attributable to the higher interest burden. [18][Factset]

Even as debt skyrocketed, Neiman was not using this debt to grow the business. Capex/revenue remained roughly flat at ~3%. Store count growth was also not significant. While on paper, total store number more than doubled, full-line Neiman and Bergdorf stores barely grew. During the holding period, full-line stores grew from 37 to 43. Recall that this growth was all preplanned—San Antonio, Boca Raton, Charlotte, Austin, Topanga (Boston and Long Island 2008 plans were canceled due to the Great Financial Crisis). [18][BBG Terminal]

Thus, the 2005 LBO of NMG left the company saddled with over ~$3.3bn of debt, with little growth to show for it.

2013 SBO (ft. Ares and CPPIB)

By 2013, it had been eight years since Warburg Pincus and TPG took NMG LLC private through the entity Neiman Marcus Group LTD LLC. The sponsors were ready to exit, and NMG announced plans to IPO.

However, these IPO plans were soon scrapped as other PE firms displayed interest in a “secondary buyout” (SBO) of Neiman. By October 2013, Ares and the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB)—a professional investment management organization managing Canadian Pension Plan assets—purchased Neiman Marcus from Warburg Pincus and TPG for approximately $6bn, funded primarily through debt. Detailed deal terms were not disclosed, however, we can do some rough math to estimate returns. Free cash flows from the holding period of 2006-2013 sums to ~$1.25bn. With $3.3bn of debt, net debt at exit would be ~$2bn. If the sponsors exited at $6bn, exit equity value is ~$4bn. Given they entered at $1.55bn, MOIC is roughly 2.7x, which translates to an IRR of roughly 12%. [1][22]

Pre-SBO, after the principal was gradually paid from 2005-2013, Neiman had $2.7bn in long-term debt, including debentures expiring in 2028. Following SBO, Neiman’s funded debt consists of a $2.8bn senior secured term loan facility maturing October 2020 (“2013 Term Loan Facility”), a $900mm senior secured asset-based revolving credit facility (“ABL Facility”), $960mm 8.000% Unsecured Senior Cash Pay Notes due 2021 (“Unsecured Cash Pay Notes”), $600mm 8.750%/9.500% Unsecured Senior PIK Toggle Notes due 2021 (“Unsecured PIK Toggle Notes”), and $125mm 7.125% Senior Debentures due 2028 (“2028 Debentures”). Together, this totals ~$5.4bn, though the facilities were not fully drawn, so total debt was really $4.7bn. On a FY2013 adjusted EBITDA of $644mm, the SBO sponsors paid a 9.3x multiple, with the new leverage sitting ~7.3x. Eyeing this heavy leverage, on October 7th 2013, debt was downgraded from B2 to B3. [26][32][BBG Terminal]

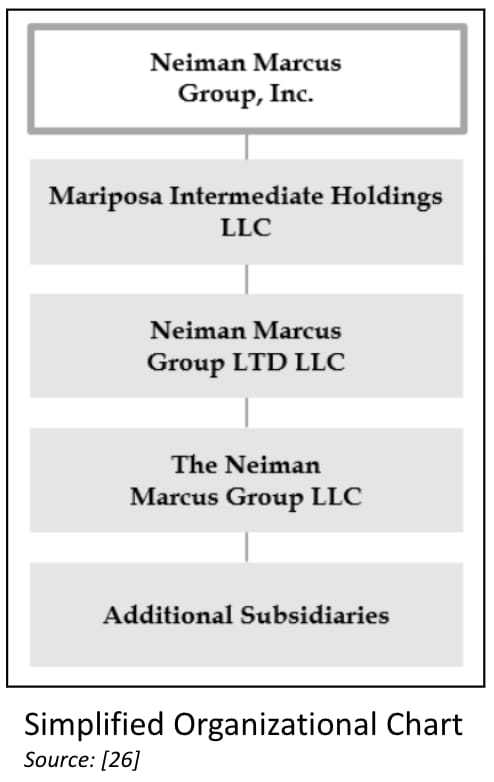

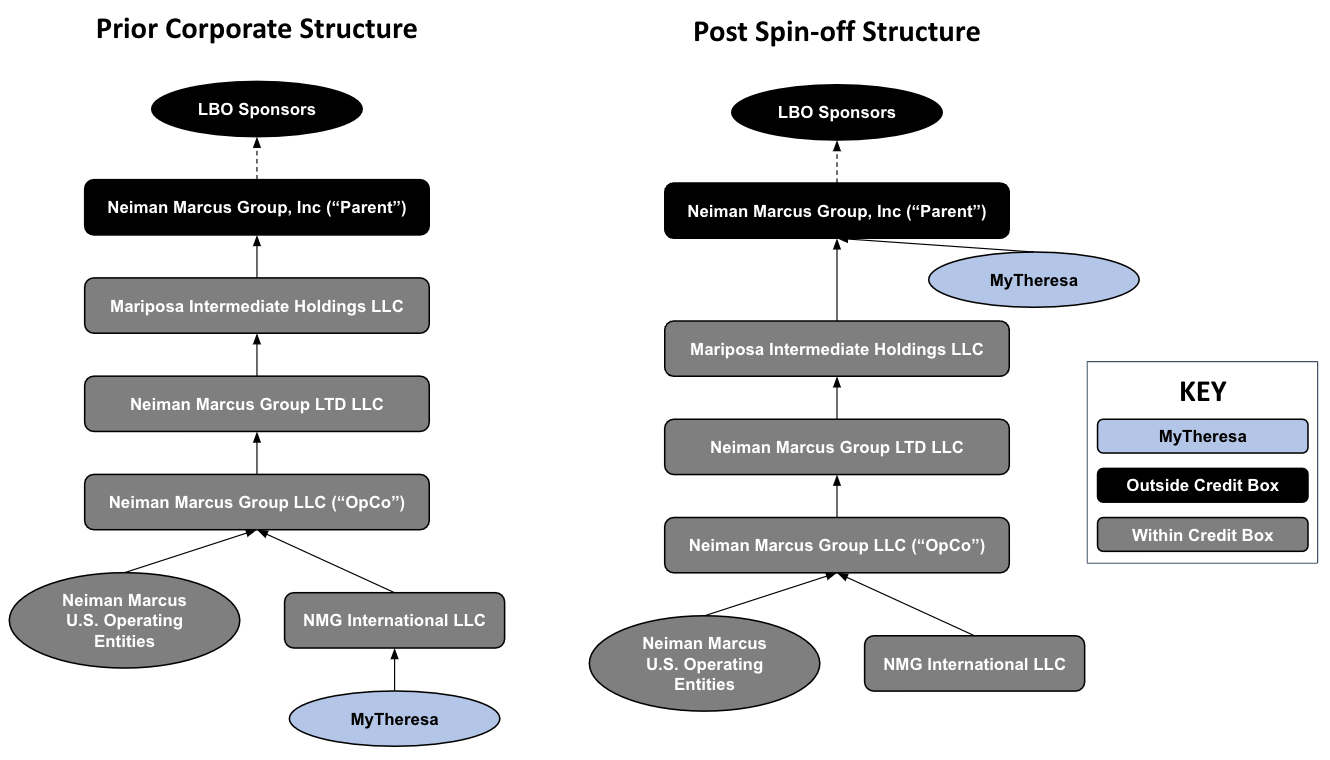

The acquisition of NMG LTD LLC was structured through a new non-debtor parent called Neiman Marcus Group, Inc. (a.k.a. “NMG Inc.” or “NM Mariposa Holdings, Inc.”) and debtor Mariposa Intermediate Holdings LLC (“Mariposa Holdings”). The resulting organizational structure looked something like this: [26]

The ultimate parent, NMG Inc., has never been an obligor or guarantor of any of the debtors’ debt. In other words, the ultimate parent is outside the credit box. The debtors’ funded debt obligations have always been issued or guaranteed by Mariposa Holdings, NMG LTD LLC, NMG LLC, and certain guarantor subsidiaries. This fact will become crucial during the MyTheresa drop-down. [26]

Operations-wise, in the twelve months leading up to April 2014, Neiman generated $4.5bn in revenues and an adjusted EBITDA of $623mm. At the time of SBO, Neiman operated 79 stores—41 Neiman Marcus stores, two Bergdorf Goodman stores, and 36 Last Call outlet centers. Alas, things would only go downhill under Ares and CPPIB ownership.

From 2013-2017, things were really not looking too good. Topline remained largely stagnant, from $4.6bn to $4.7bn, mainly driven by a slow retail environment in 2016 and 2017. Muted U.S. economic trends, a sea change away from in-store to shopping online, reduced tourist spending due to strong U.S. dollar, and integration challenges with a new inventory management system led to weak earnings. Beginning 2017, comparable-store sales had declined for five consecutive quarters and fiscal trailing 12-month adjusted EBITDA was down 19% year-over-year. Online sales were flat for fiscal 1Q 2017, with domestic softness balanced by continued growth for the company's international online business, MyTheresa. [15]

Excluding MyTheresa, NMG EBITDA margins had historically hovered around 13-14%. By 2017, margins were 9.4%; in 2018 a mere 10.1%, while adjusted EBITDA nearly halved from 2015-2018. Debt remained roughly flat. Net interest in FY2016 was $286mm, increasing to $296mm by FY2017. In FY2017, net income was -$532mm. [15][32][33]

It’s easy to get lost in the numbers here. Compared to Hertz’s $19bn of debt, or PG&E’s $22bn of debt, $5bn of debt might seem relatively trivial. However, we need to keep in mind that this $5bn of debt is supported by a two-digit store count. Moreover, prior to SBO, net income averaged around $100-150mm; now, Neiman was shouldering upwards of $250mm+ of annual interest.

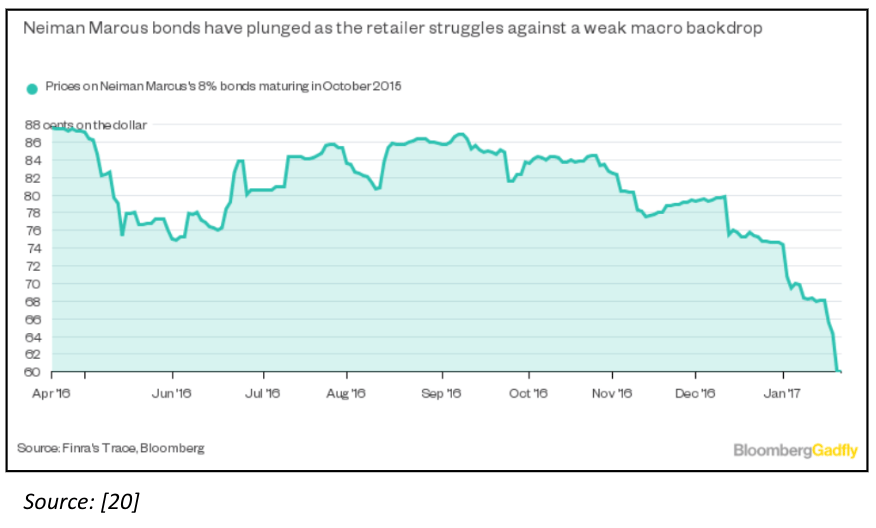

The market recognized the precariousness of the situation. Early January 2017, Neiman Marcus's term loan was trading at ~86 cents on the dollar. Bonds were trading in the 60s. By March 15th 2017, Neiman’s credit rating was downgraded from B3 to Caa2; Neiman faced a subsequent downgrade shortly after, on October 26th 2018, from Caa2 to Caa3. [20][32]

Ares and CPPIB had had enough.

A mere two years after their SBO, the sponsors were ready to exit. In 2015, Neiman Marcus had announced plans to IPO, but delayed to 2016 due to stock market volatility. In 2016, IPO dollar-volume was down 42% year-over-year. By 2017, as they faced weaker customer demand, Neiman withdrew their IPO plans, and pushed a revolver maturity from 2018 to 2021. [20]

The sponsors realized they were in this for the long haul, and by early 2017, Neiman retained Lazard to explore potential liability management transactions, including asset sales, debt exchanges and other strategic transactions. They first considered a sale of their U.S. operations, called Project Harry, to another luxury retailer. After that transaction terminated, the parties began negotiations early 2018 on another deal known as Project Einstein, which would have resulted in Neiman obtaining another luxury retailer’s operations in exchange for Neiman’s real estate interests. Those discussions ended in late July 2018. It was only then that the sponsors looked towards a drop-down of MyTheresa. [26]

MyTheresa

We’ve briefly mentioned it a few times prior, but now is time to properly introduce Neiman’s crown jewel: MyTheresa.

The international e-commerce platform, mytheresa.com, traces its roots back over 30 years to a luxury boutique in Munich, Germany. In October 2014, NMG acquired the online business of MyTheresa and its physical store in Munich for $196mm (plus a later $57mm in two contingent earn-out payments) to expand its e-commerce platform and international presence. Since then, MyTheresa has operated on a standalone basis, with its own CEO, CFO and management team, as well as separate vendors, suppliers, and bank lenders. After acquisition, the German entities that operate MyTheresa sat under a series of German and Luxembourg holding entities which fell under the subsidiary, NMG International LLC. As such, MyTheresa was located well within the credit box. [4][26]

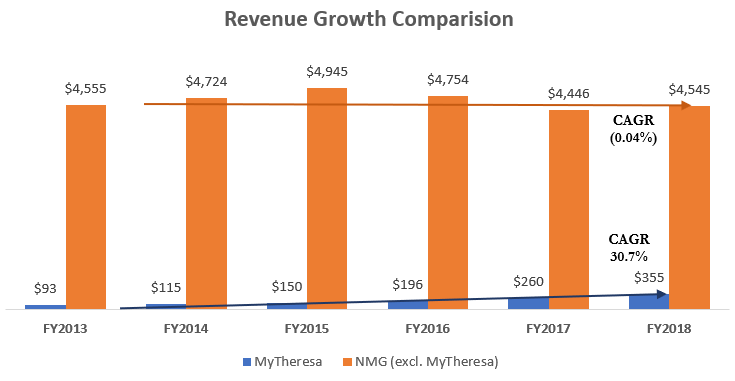

By 2018, MyTheresa had grown into a major e-commerce platform then valued at ~$282mm. It was the only growing asset in the otherwise stagnant portfolio of Neiman Marcus Group Inc. From FY2013 to FY2019, MyTheresa’s revenue catapulted 360% from $93mm to $428mm—a 29% CAGR. From FY2014 to FY2018, MyTheresa’s revenue grew at a CAGR of 30.7%, while NMG’s revenue (excluding MyTheresa) declined at a CAGR of -0.04%. [26][32]

Drop-down: No Longer (our)Theresa

So here’s the situation: PE sponsors own a company that is now in distress. This company in turn owns a valuable asset worth $282mm (likely more) that is the only fast-growing unit in an otherwise struggling portfolio. One of the sponsors is notoriously good at financial engineering. Can you guess what happens next?

While in hindsight it doesn’t take a genius to connect the dots, at the time, the drop-down came as a surprise. Before the 2018 transfer, there was some anticipation that NMG would use the MyTheresa shares to entice bondholders to swap their debt for bonds with a longer maturity. In other words, a distressed debt exchange involving MyTheresa shares as collateral. [12]

Ares and CPPIB had other plans.

Before we examine what actually happened, it is worth defining what a drop-down is. It is a type of liability management exercise that entails the use of basket capacity under existing investment and restricted payment covenants to transfer assets from the entity that guarantees its debt (restricted subsidiary) to another entity that is not subject to the same creditor claims (unrestricted subsidiary). The unrestricted subsidiary, backed by the “dropped-down” collateral, is then free to issue new debt which is structurally senior to old claims on the restricted subsidiary. We can think of this as a form of asset stripping, where assets are moved outside the “credit box.”

Of course, creditors are not clueless, and there are a litany of negative covenants to protect against asset stripping. The ingenuity of the Neiman drop-down was how the sponsors utilized a series of exceptions to outline a loophole where they could distribute a $282mm business line to themselves during a period of uncertain financial stability without triggering covenant breaches under multiple credit facilities. [1]

The Neiman drop-down occurred in two steps. First, in stages from 2014-2017, Neiman designated the MyTheresa entities as unrestricted subsidiaries under its existing debt documents. Second, Neiman distributed the unrestricted subsidiary’s equity to the NMG parent company (a.k.a. sponsors) through dividends. By utilizing loose credit documents, Ares and CPPIB were able to move the equity of MyTheresa out of the credit box and into their own hands. Let’s take a closer look.

Step 1: Unrestricted Subsidiary Designation (2014-2017):

Upon acquisition, MyTheresa was within the credit box, and thus were “restricted subsidiaries” subject to the affirmative and negative covenants of the credit facilities. However, they were not guarantors under the Term Loan and ABL Credit Facilities—meaning creditors did not have a lien on MyTheresa assets. This meant that Neiman would not have to worry about structuring the transaction and garnering votes to release liens, as in cases like PetSmart and Incora. [1]

But wait, if the creditors never had claim to these assets as collateral, why would they care about MyTheresa in the first place? And shouldn’t they care even less after MyTheresa is unrestricted and not even subject to covenants? Well, NMG International, the foreign subsidiary holding company wholly owned by NMG which held the MyTheresa assets, had 65% of its equity interests pledged on a first-lien basis in favor of the senior secured lenders, meaning that creditors had an indirect claim on MyTheresa equity as part of collateral. Any distributions on account of an unrestricted subsidiary’s capital stock would flow up to the loan party group, thus providing secured creditors indirect credit support through ownership in the subsidiary rather than an asset claim. Note that despite 65% pledge of NMG International’s equity interests in favor of the senior secured lenders, no MyTheresa entity’s equity was directly used to guarantee any of the Debtors’ obligations at any point. [1][26]

With that out of the way, let’s take a closer look at this drop-down. Because Step 2—where the claim on equity value is transferred directly to the parent outside of the credit box—is only possible with unrestricted subsidiaries, Step 1 was to convert these restricted subsidiaries into unrestricted subsidiaries.

Neiman’s debt instruments had several negative covenants placing parameters around unrestricted subsidiary designation, limiting investment capacity, and limiting dividends. However, these facilities had exceptions through “baskets” which quantify the maximum dollar amount for a specific exception to a covenant restriction (e.g. you can issue at most $X amount of dividends). Because Neiman had multiple credit facilities, they would have to move MyTheresa outside the credit box for each facility by utilizing basket capacity.

Each credit facility permitted Neiman, specifically NMG LTD LLC, to designate any restricted subsidiary as an unrestricted subsidiary subject to no event of default and sufficient investment capacity. Other requirements include a minimum of $225mm in excess availability on the ABL facility, and a minimum Fixed Charge Coverage Ratio of at least 1.0x on a pro forma basis for the term loan facility. [1]

In 2014, Neiman designated the MyTheresa entities as unrestricted subsidiaries under the ABL facility and the term facility. In 2014, the MyTheresa entities were valued ~$253mm, well below the $502mm of investment capacity from Neiman’s builder investment basket, general investment basket, and foreign subsidiary investment basket. [1]

In 2017, Neiman designated the MyTheresa entities as unrestricted subsidiaries under its note indentures as well. Though the MyTheresa entities were now valued at ~$280mm, there was basket capacity to spare given the $578mm of investment capacity through Neiman’s builder basket and general investment basket. [1] [26]

So, by March 2017, Neiman had successfully designated the MyTheresa entities as unrestricted subsidiaries under all of its debt facilities, and Step 1 of the spin-off was accomplished. While MyTheresa remained in the credit box, there was now a channel out.

STEP 2: Asset Stripping (September 2018)

For 18 months after unrestricting the MyTheresa assets, Neiman just sat on their assets. That changed in September 2018, when Neiman disclosed that the MyTheresa subsidiaries had been conveyed through a series of distributions to NMG Inc. (“Parent”), a hold-co wholly-owned by the sponsor, which, as we might recall, did not guarantee debt and thus was outside the credit box. Mariposa Luxembourg I (the highest level foreign hold-co which held MyTheresa assets) shares that had been distributed to NMG Inc. were then moved into a series of new MyTheresa holding entities: MYT Parent Co., MYT Holding Co., and MYT Intermediate Holding Co. Any value generated from MyTheresa would flow up directly to the Sponsors, bypassing lenders. [1][26]

So, what exactly were these “series of distributions”? Credit facilities usually prevent credit box “leakage” by restricting a company’s ability to make dividends and distributions. However, as in Step 1, each of the credit facilities contained an exception—an exception the sponsors were unafraid to utilize.

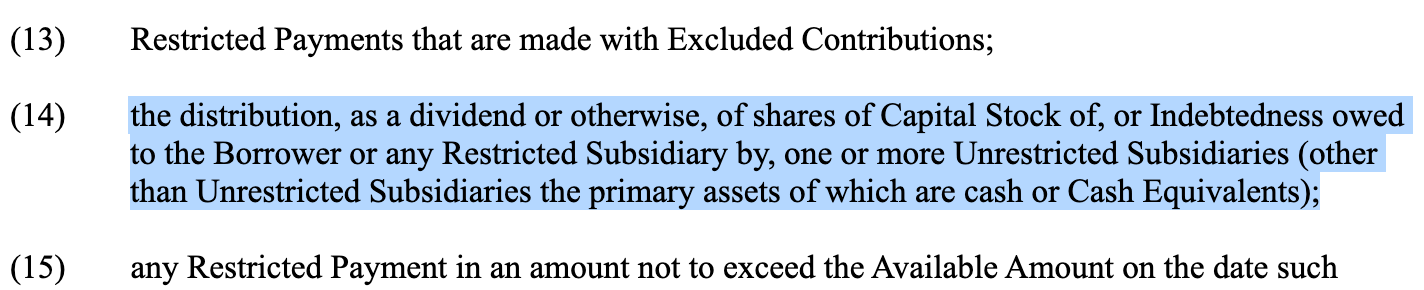

An express provision (a.k.a. explicitly stated) to the limitation on restricted payments stated that Neiman was allowed to make a “distribution, as a dividend or otherwise, of shares of Capital Stock of, or Indebtedness owed to the Borrower or any Restricted Subsidiary by, one or more Unrestricted Subsidiaries.” Thus, Neiman could make a dividend of the equity of any unrestricted subsidiaries, such as the MyTheresa entities, and effectively “spin-off” that equity outside the credit box. As a result of the spin-off, the sponsor-owned parent NMG Inc. now owned 100% of the capital stock of the MyTheresa entities. Step 2 of the drop-down was complete. [1][32]

Aftermath

Neiman’s drop-down was by no means the first (e.g. 2016 J. Crew drop-down, June 2018 PetSmart drop-down); however, it was yet another precedent where borrowers exploited fairly common baskets in a credit agreement’s negative covenant which were originally intended to preserve flexibility for debtors to pay dividends. As mentioned above, these baskets serve as an exception to what may otherwise seem extremely restrictive covenants (e.g. a debtor would be much more amenable to a covenant that allows them to issue at most $X dividends compared to a covenant that does not allow dividend issuance).

When creditors realized MyTheresa was no longer their MyTheresa, they were, unsurprisingly, not happy. Because this spin-off was effectuated as a dividend rather than a sale…

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals