Welcome to the 140th Pari Passu newsletter.

Before we get started, a huge thank you for all the nice words of support received as a response to our Saks write-up from earlier in the week. It was a massive lift to get this out quickly to make it relevant for all of you, and it was awesome to see such a positive reaction.

Like many travel-adjacent companies, GEE filed for Chapter 11 shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, COVID wasn’t the true cause of GEE’s bankruptcy; instead, it was a couple of poor decisions years prior. GEE provides a case study in how top-line growth can hide the structural flaws of rising leverage and poor capital allocation.

This situation also serves as a cautionary tale for investors considering rescue financing, as we’ll see how a single investor injected nearly $200mm of capital but walked away with less than a 1% recovery. We’ll also cover the importance of a senior position in the capital structure during a Chapter 11 restructuring, especially a 363 sale, where Apollo and other lenders were able to credit bid their claims for control of GEE.

This write-up examines how, despite very strong top-line growth, GEE’s cost structure, excessive leverage, and a poorly timed investment set the stage for an inevitable Chapter 11. We’ll also cover the company’s business model, SPAC roots, and its (almost) successful pre-COVID turnaround.

Why defining a Credit Data Strategy is now existential for Credit Investors

As AI rapidly advances, credit investors who fail to leverage its potential will find it impossible to compete with more agile peers in terms of both performance and AUM. The best way for firms to position themselves for the market’s continued digital evolution is to define a “Credit Data Strategy”. Recorded in partnership with the European Leveraged Finance Association, Cognitive Credit Founder and CEO, Robert Slater, explains what a best-in-class, data-driven approach to credit research looks like in 2025 in this on-demand webinar. Topics include:

How real-time fundamentals can drive faster decision-making.

Leveraging structured data & automation to unlock operational efficiencies

Using advanced analytics to enhance credit portfolio management

Best in class-examples for 2025

Cognitive Credit is the market's premier provider of fundamental credit data and analytics for credit investors. Want to see how our data & analytics could make 1Q25 earnings easier? Request your demo today.

Business Model

Global Eagle Entertainment (“GEE”) operated two distinct business segments: connectivity and media.

Connectivity

The connectivity segment installed and operated satellite-based internet access onboard aircraft, enabling customers to browse the internet, stream entertainment, check social media, or access any other online content with a Wi-Fi connection [1]. GEE originally provided connectivity services to airlines, but would eventually grow to serve maritime and remote (land-based customers without access to traditional internet) customers as well. The company’s primary offering was “Airconnect”, a white-labeled connectivity service and app. White label means that customers can brand the Wi-Fi service as their own and charge flyers at a rate they please. For example, Southwest Airlines rebranded GEE’s connectivity as “SouthwestWiFi” and charged a fee (such as $8) per flight for flyers to connect, meaning GEE essentially acted as a connectivity wholesaler from which Airlines could purchase connectivity and sell to flyers. Revenue models varied by customer, but usually fell into one of two categories: fixed monthly fees or revenue-sharing agreements [3].

Customers who opted for a fixed monthly fee were charged monthly per aircraft in exchange for full connectivity coverage. These agreements typically lasted from three to nine years, providing revenue consistency. For reference, Southwest Airlines, GEE’s largest customer, accounting for 21% of revenue in 2019, fell into this category. Additional notable customers include Norwegian Air, Turkish Airlines, and Air France.

On the other hand, customers under revenue-sharing agreements paid GEE a portion of the fees they charged flyers. This allowed customers to offer connectivity with less upfront costs. While specific proportions aren’t disclosed, revenue sharing agreements made up the “lesser extent” of connectivity service revenue [3].

GEE positioned itself as the platform layer in the in-flight connectivity and entertainment (IFCE) scene. While the company provided satellite internet, it did not own any satellites itself. Instead, it leased satellite bandwidth from various satellite operators. These lease agreements were typically structured as long-term, take-or-pay contracts for specific coverage areas, such as flight corridors. In a take-or-pay contract, GEE pays a fixed rate, regardless of the amount of bandwidth used [3].

Media & Content

GEE’s Media and Content segment provided in-flight entertainment (IFE) and other digital media services to customers. For perspective, the Media segment accounted for 47% of 2019 revenue, while the Connectivity segment accounted for 53% [1]. It primarily purchased and licensed content (including movies, TV shows, games, etc.) for airline customers. GEE offered content on its digital platform, “Airtime”, which powered white-labeled entertainment portals. Airtime paired well with Airconnect (GEE’s white-labeled offering) by allowing airlines to embed content selection in their portals, a common feature on today’s airlines. Airtime also included content-ancillary offerings such as multilingual subtitles, game selections, and curated playlists.

GEE sourced licensed content through direct relationships with Hollywood studios and regional film distributors. Occasionally, GEE would localize content itself to suit consumer needs by translating or subtitling select content.

Content revenue came from two primary sources. The first source was contracts with airlines and other customers, typically spanning multiple years. Under these contracts, GEE might update content offerings monthly, while fees are tied to the number of aircraft served and the amount of content offered. The second source of revenue was advertising. GEE monetized its media offerings through digital advertisements, including preview video ads, banner ads, and other sponsored content. While customer contracts were the larger source of revenue, the company did not disclose the exact split between the two revenue streams. The contract-based nature of the content segment provided more consistent top-line numbers than the connectivity segment, which included usage-based offerings.

A key differentiator for GEE was the integration of its content and connectivity offerings. By offering both IFE and IFC on a single white-labeled platform, GEE became a one-stop shop for airlines, creating stickier revenue and reducing churn.

Corporate History & Funding

Global Eagle Entertainment was formed in 2013 through the merger of two companies operating in the in-flight connectivity and entertainment space: Row 44 and Advanced Inflight Alliance AG (AIA).

Row 44, based in the U.S., provided satellite-based Wi-Fi systems for commercial airlines. Its primary product was a high-speed Ku-band internet system that could be installed on aircraft to provide passengers with connectivity during flight. Row 44 had already secured key customers like Southwest Airlines and was gaining traction as a low-cost, high-uptime connectivity solution.

Advanced Inflight Alliance (AIA), headquartered in Germany, was a media services business that licensed, curated, and distributed entertainment content such as movies, TV shows, games, and music to airlines globally. AIA was a leading player in the in-flight entertainment (IFE) market, with clients across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

In January 2013, these two companies were combined through a SPAC transaction involving Global Eagle Acquisition Corp (GEAC), a blank-check company formed by media investors Harry Sloan and Jeff Sagansky. GEAC had raised $190mm in its 2011 IPO with the intent to find and merge with a media or entertainment business. The deal valued the combined company at approximately $430mm, with the new entity assuming the name Global Eagle Entertainment Inc.

This transaction created an integrated in-flight connectivity and entertainment provider, capable of offering both satellite-based internet and curated content to airlines and other customers. At the time of the merger, the combined entity had little to no debt and recorded $260mm of revenue. Regardless, the newly formed GEE was struggling to break even in terms of profitability. However, this would quickly change as GEE rapidly scaled its customer base.

Over the next six years, GEE would grow rapidly, driven by strong demand and a series of acquisitions. The most notable transaction was GEE’s $550mm 2016 acquisition of Emerging Market Communications (“EMC”), a provider of satellite connectivity to cruise ships, yachts, and remote islands. This transaction expanded GEE's customer base from just airlines to maritime and remote customers as well. By this time, GEE had depleted much of its cash balance on building out its platform, and despite strong top-line growth, it continued to not generate profits. GEE paid $550mm for EMC, which consisted of $370mm of debt (assumed from EMC’s balance sheet), $100mm in cash, and $80mm in stock. Notably, the $370mm represented a large increase in debt relative to GEE’s pre-transaction balance sheet. To illustrate this impact, GEE’s 2015 interest expense before the transaction was just $2mm. In 2017, the company paid $58mm of interest.

Shortly after this acquisition, in 2017, GEE refinanced the EMC debt with a new $500mm senior secured term loan due 2023 and a $85mm revolving credit facility (RCF) due 2022. This new facility carried an interest rate of EURIBOR + 6.50%. EURIBOR stands for Euro Interbank Offer Rate; think of it similarly to SOFR, but for Euro-denominated lending. Additionally, it’s important to know that EURIBOR was effectively 0% at the time, in an effort by the European Central Bank to stimulate economic activity. While GEE was headquartered in Los Angeles, AIA (the content segment subsidiary) was based in Germany, and the credit facility was issued from a German legal entity, hence the use of EURIBOR. Additionally, this 2017 refinancing provides a significant inflection point from which we can view GEE’s financial profile. We’ll start by examining the first period, 2013-2017, and follow with the period from 2017 to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Growth and Investor Sentiment

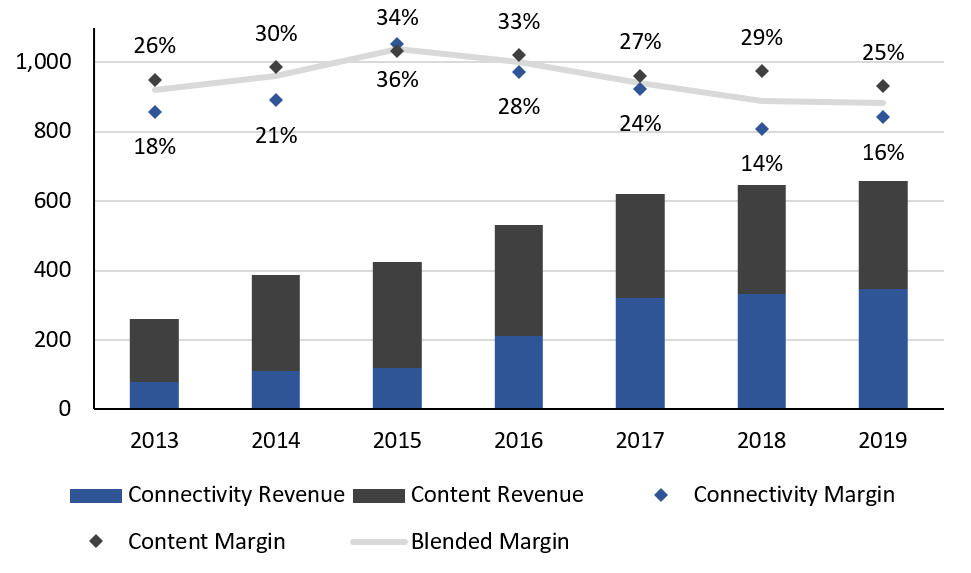

When GEAC (the SPAC) acquired Row 44 and AIA in 2013, the combined entity generated $260mm in revenue, with the connectivity segment accounting for 30% and the content segment accounting for 70%.

From 2013 to 2017, revenue grew at a CAGR of 24%, with the majority of this growth being driven by the connectivity segment. For reference, the content segment grew at 13% from $182mm to $277mm over this period, while the connectivity segment grew at a CAGR of 42% from $78mm to $321mm in 2017, surpassing the size of the content segment. This reflects the growing demand for in-flight connectivity during the mid-2010s [3].

In terms of investor sentiment, despite GEE’s rapid growth in the subsequent years, the company’s market cap actually peaked during February of 2014, just shortly after the SPAC merger closed, at over $1.1bn. For example, for much of 2017, its market cap trended around $250mm, less than a quarter of its 2013 valuation, despite generating more than twice as much revenue.

This initial surge in valuation reflected investor views on what at the time was an emerging technology. Additionally, it showcased the familiar trend of bullishness surrounding post-SPAC valuations. These two factors drove GEE’s market cap up to nearly 3x its original valuation, as the industry’s newest vertically integrated IFEC provider.

However, despite continued revenue growth, investor sentiment gradually shifted as it became clear that its expanding top line was not translating into profitability. While GEE had nearly doubled its size through acquisitions, persistent losses raised questions from investors about the company’s long-term viability. This disappointment was magnified by the company’s rising leverage, which steadily eroded profitability, further continuing the decline in market valuation. In the next section, we’ll dive into the primary cause of both lagging gross margins and a rising debt load.

Figure 1: Revenue and Gross Margin by Segment [3]

EMC Acquisition Analysis

Using the chart above, which provides a full picture of GEE’s growth and profitability, let’s examine how GEE’s profitability and cash flow began to erode.

First, GEE’s acquisition of EMC in 2016 was ill-timed and margin-dilutive. Contrary to GEE’s expectations, maritime and land connectivity markets ended up being significantly less profitable than the company’s core aviation connectivity segment. In 2016, for example, the new Maritime and land (“M&L”) segment reported a 19% gross margin, while the aviation segment reported 34% (2016 was the only year that GEE reported separate maritime and aviation segments, but it provides enough information to draw conclusions). While the acquisition of EMC did add roughly $73mm of incremental connectivity revenue, it dragged the overall connectivity margin down to 28%, an 8% decrease from the prior year [3].

To analyze the true financial impact of this acquisition, we’ll use some simplified unit economics. Let’s outline what we know about this transaction:

$100mm cash was paid.

$370mm of EMC debt was assumed.

$80mm in new shares were issued.

This debt was quickly refinanced at EURIBOR + 6.50% (6.50% effective rate).

The resulting interest expense was $24mm ($370mm x 6.5%).

Maritime and Land Connectivity gross margin was roughly 20%

Ignoring the cash portion of the acquisition and any other expenses, at a 20% gross margin, the M&L segment would have to generate $120mm in revenue ($24mm / 20%) to cover the associated debt’s interest expense alone. Unfortunately for GEE, the 2016 M&L segment recorded just $73mm of revenue in 2016, resulting in contribution profit of just $14mm, which doesn’t even cover interest alone [3].

In addition to servicing debt from the acquisition, GEE also paid $100mm in cash and diluted its current shareholders. Stepping back, it’s clear that GEE would have to rapidly grow revenue while expanding margins to make the acquisition profitable, a task that management underestimated in its difficulty.

While this simple analysis reveals the mathematical flaws of the EMC acquisition, the true flaw in the acquisition, as in most, came from the mismatch between expectations and reality. This mismatch can be boiled down to a few reasons.

Firstly, M&L, particularly installation costs, was simply more capital-intensive than aviation. The M&L segment involved a larger number of vessels to serve, including cruise ships, yachts, commercial shipping vessels, etc. Each ship required antennas, modems, routers, and other infrastructure. As the company put in its 2018 annual report, “Our maritime and land business is more capital intensive and has a larger number of vessels to serve” [3]. In addition to being capital-intensive, installation periods for maritime customers typically lasted much longer than aviation installations, as cruise ships and oil rigs are much larger than aircraft, requiring more connectivity infrastructure. When examining unit economics per vessel, this factor delayed payback periods on the upfront investment, as new contracts wouldn’t generate revenue until a full installation of hardware, which could take months.

Additionally, to build out its M&L connectivity network, GEE had to lease new satellite bandwidth. Recall that the company selectively leased bandwidth in standard flight corridors for its Aviation segment. However, to build out maritime connectivity, the company had to lease bandwidth in areas far from these flight corridors. This new bandwidth, often structured as take-or-pay contracts, was inherently less profitable because maritime vessels do not follow the same structured routes. This means GEE leased more geographical bandwidth and received less utilization as a result.

The effect of the above factors is twofold. First, installing new hardware was expensive, and the company saw material increases in capital spend. Second, GEE leased additional satellite capacity at a lower bandwidth utilization. This means that for every dollar of fixed bandwidth cost, there was less revenue to support it, which lowered the overall gross margin. These two strains on cash, combined with interest expense, resulted in increased cash burn following the EMC acquisition.

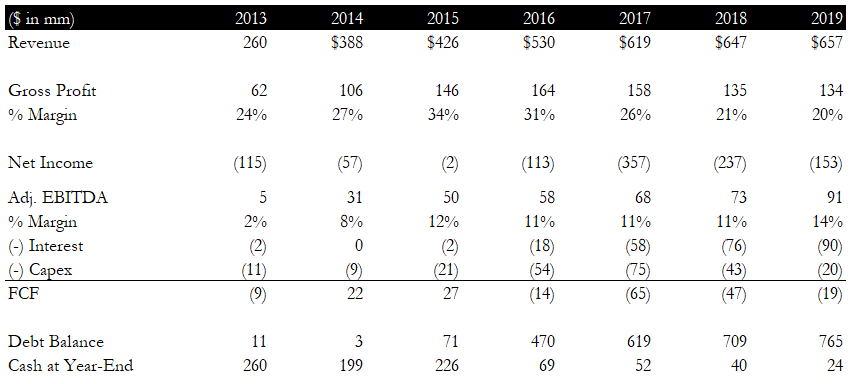

From 2015 to 2017, total revenue grew from $426mm to $619mm while EBITDA grew from $50mm to $68mm, representing 12% and 11% margins respectively. From 2015 to 2017, debt increased from $71mm to $619mm, reflecting the assumption of EMC’s debt and the subsequent refinancing into the aforementioned 2017 facility. As a result of this increase, interest expense increased from just $2mm in 2015 to $58mm in 2017 [3]. While the EMC acquisition contributed to top-line and EBITDA growth, the incremental profits were not enough to justify the added interest burden. This mismatch materially increased cash burn and strained GEE’s ability to fund its operations. The table below provides a high-level overview of GEE’s financial profile from 2013 to 2019.

Figure 2: GEE Financial Profile [3]

2018 Searchlight Capital Injection

In early 2018, GEE began facing the possibility of a liquidity issue. The company started the year with $52mm in cash and $1mm available under its RCF, resulting in just $53mm of liquidity. If cash burn were to accelerate or remain at 2017 rates, the company would quickly run out of cash. Recognizing this fact, the company looked to raise additional debt capital [3].

On March 28, 2018, Searchlight Capital Partners invested $150mm of new capital in exchange for second-lien notes due June 30, 2023. Proceeds were used to fully pay down the drawn portion of the RCF and to provide operational liquidity. These notes carried a 12% PIK interest rate, which would later switch to 10% cash. In addition to the second-lien notes, Searchlight received equity warrants for 18.1mm shares at a $0.01 exercise price and 13mm shares at a $1.57 price. For reference, this represented roughly 30% of the company’s common stock. These warrants were only exercisable if the company’s stock price exceeded $4 [3]. For reference, it was trading in the low $1 range at the time, meaning these warrants indicated that Searchlight was betting on a major turnaround for the company. Additionally, Searchlight received two board seats in this transaction, allowing the firm to play a role in the turnaround it foresaw.

This investment gave GEE a second chance by providing enough runway to turn around operations. The primary method of turnaround was a three-phase cost reduction program, which the company referred to as its “Cost Realignment Plan” [3]. This plan included renegotiating contracts, consolidating operations centers, automating basic operational functions, and other pure-play cost-saving measures. One notable saving was the renegotiation of two major bandwidth contracts from take-or-pay to volume-based discounts, directly benefiting the bottom line of underutilized regions.

Additionally, the company refocused future investment on its core, more profitable airline segment within connectivity. This was made possible by GEE’s new lease agreement for a Ku-band high-throughput satellite (HTS) network, the first of its kind to span Europe, Russia, Scandinavia, and North Africa. GEE accelerated HTS installations, particularly with Air France, to quickly provide the company with higher margin revenue [3].

GEE’s cost-reduction plan initially proved successful. By Q2 2019, the company reported achieving 90% of its Phase II cost-savings initiatives. The numbers backed this statement up as well. 2019 EBITDA soared to $91mm, and the company only burned $19mm in cash, relative to the $65mm it burned just two years earlier. The future was looking bright(ish) for GEE (despite substantial improvements, the company was still footing interest expenses of $90mm in 2019). While the margin for error was small, GEE predicted that the continued rollout of the HTS connectivity and cost controls would bring the company to positive free cash flow in 2020 [3].

COVID-19 Pandemic

Unfortunately for GEE, the COVID pandemic put a near-immediate halt to the company’s turnaround plans. Over the course of a few weeks, air travel collapsed, and cruises were halted. In March 2020, global airline seat capacity fell by over 90% as governments imposed travel bans and airlines parked their fleets. Cruises suffered the same fate, with cruise lines suspending trips. In response, GEE accelerated its cost-cutting efforts, lowering salaries by 20-30% and initiating layoffs. Additionally, the company nearly drew down the remaining $37mm of its entire $85mm revolver once again, leaving the company with total liquidity of $54m entering the pandemic [2].

Outside of its capital structure, the reason GEE was poorly positioned for the COVID pandemic came down to the mismatch between cost and revenue structures. As a reminder, the company leased satellite bandwidth on long-term contracts. While it had renegotiated some contracts to be volume-based, they likely still had large minimum payments. Additionally, contracts that weren’t adjusted would still be on take-or-pay terms. In terms of revenue, GEE had three types of agreements: “a set fee for each enplaned passenger, a fee based on usage by passengers, or flat rates per installed aircraft” [3]. While the grounding of planes did reduce some lease costs, it is very likely that the hit to revenue severely outpaced the volume-based discounts, not to mention GEE’s other fixed costs, including wages and interest expense.

Q2 2020 revenue nearly halved to $83mm from $144mm in Q1 of 2020, and by the end of June, the company had already burned through the entire revolver draw and the majority of cash on hand. With a $22mm interest expense each quarter, a Chapter 11 filing seemed inevitable for the company, and it began discussing with lenders in Q2.

The Restructuring

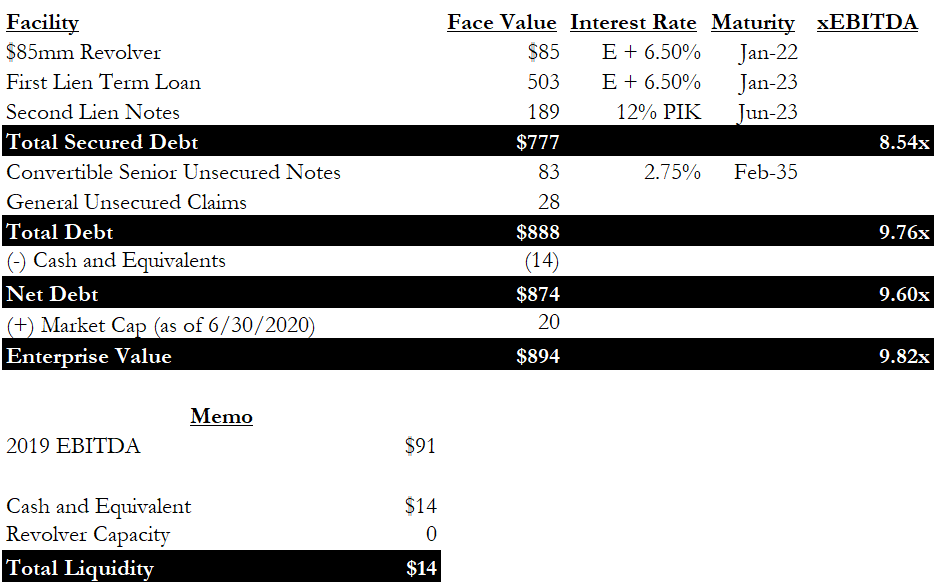

GEE filed for Chapter 11 on July 22, 2020, in the District of Delaware, with approximately $1.1bn in funded debt. Additionally, the company had already negotiated a Restructuring Support Agreement with the majority of its first-lien term loan lenders (represented by Apollo, who had bought up a large amount of first-lien debt as it traded at distressed levels). As a reminder, an RSA proposes a plan and solicits creditor support before the debtor files, aiming to speed up the in-court process. The company filed with the following capital structure:

Figure 3: Pre-petition capital structure [2]

A couple of notes on the chart above: first, while the term loan was issued in the amount of $540mm, it featured 2% annual amortization, bringing the pre-petition balance down to $503mm. Also, while Searchlight provided $150mm of second-lien notes, the $189mm reported at filing included the PIK interest that had accrued.

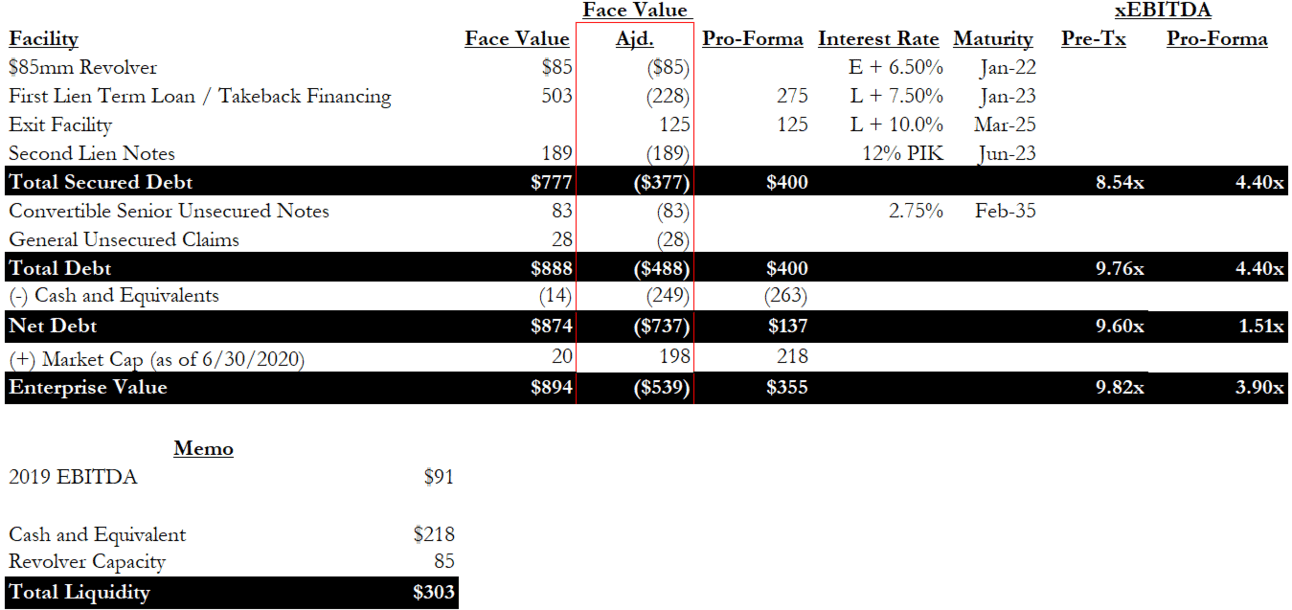

The RSA, which had support from roughly 90% of first-lien lenders, Searchlight’s approval, and 80% of unsecured notes, proposed a section 363 sale sale of the company, with first-lien lenders playing the role of stalking horse bidder (see our Section 363/Credit Bid writeup for a great explanation of mechanics.). As stalking horse bidder, the first-lien lenders bid the entirety of their roughly $588mm secured claim (Term loan outstanding plus drawn RCF) in exchange for full control of GEE and its assets. This bid included $275mm of takeback term loans, with the remainder being a credit bid. This means that first lien lenders weren’t bidding with cash. Instead, the face value of the entire first lien credit facility would be reduced to $275mm post-petition [2].

In addition to the credit bid, the RSA also proposed two other key components. The first was an $80mm DIP loan, provided by an ad hoc group of first-lien lenders, to fund the in-court process. The second component was a $125mm exit facility, provided by the same group, to refinance the DIP facility and provide fresh capital to GEE. To clarify, the $125mm exit facility can be distinguished as new money debt, providing fresh cash to the business. On the other hand, the $275mm takeback debt consisted of part of the pre-petition term loan, rolled into the new facility. Under the RSA, total debt upon emergence was not to exceed $400mm ($125mm + $275mm)[2].

Following the 363 auction process, Apollo and other first-lien lenders emerged as the winners and took control of the company. Given the fact that this auction took place at the peak of COVID-19’s disruption to aviation and cruise travel, there was understandably limited interest from third-party buyers. Moreover, third-party buyers would have to bid $600mm+ in cash to be competitive in the auction. Apollo and other secured creditors, on the other hand, had to contribute no incremental cash for their $588mm credit bid, allowing them to be much more aggressive.

This sale process provides a great example of an offensive credit bidding strategy, also known as a “loan-to-own” strategy by Apollo. While specific purchase details are not public, Apollo was not part of the original first-lien lender group and thus bought the debt at some point on the secondary market. Assuming these purchases occurred while the debt was trading at distressed levels, likely at a material discount to par, Apollo was able to accumulate a controlling position at a reduced basis. It then used the full face value of that secured claim to credit bid in the Section 363 sale process, acquiring substantially all of the company’s assets without contributing incremental cash. This strategy effectively converted a discounted debt investment into ownership of the reorganized entity, consistent with the traditional loan-to-own model employed by distressed investors.

In addition to the new money exit facility, Apollo and the new owners made a $218mm equity investment into the reorganized GEE. The figure below shows the company’s new capital structure.

Figure 4: Pro-forma capital structure under the RSA [2]

Let’s also take a look at what other creditors recovered under the plan:

Searchlight, the provider of the second-lien notes in 2018, received just $1.75mm in cash under the plan, representing less than a 1% recovery on its $189mm claim. Searchlight was the true loser in this scenario. While the firm provided the necessary runway and helped facilitate the beginning of a GEE turnaround, it still experienced a massive loss, despite having significant equity upside. In fact, having issued a PIK interest note, the $1.75mm was the only cash Searchlight ever got back from GEE. This highlights the risk of making a subordinated debt investment in a struggling company. This effect is amplified when the investment is structured with PIK interest, since it defers cash interest and offers no interim returns, leaving investors fully exposed to downside risk.[2].

Next, all unsecured claims, including the convertible unsecured notes, received their pro rata share of $4mm [2].

GEE emerged from bankruptcy in March of 2021, rebranding as “Anuvu” in May 2021. The company’s new strategy refocuses on its legacy offerings: in-flight and at-sea connectivity. As a part of this, Anuvu sold off a portion of its non-core business segments, such as its African fixed-site land remote connectivity business. Additionally, the company is doubling down on its innovative HTS offering, signing a multi-year contract for HTS coverage over the entirety of North America [5].

While Anuvu, a private entity, no longer reports public financials, it did disclose an additional $50mm growth investment from its new owners to support its expansion into geosynchronous orbit (GEO) and eventually low Earth orbit (LEO) networks [6]. Fast-forwarding to today, the company is still striving to improve its connectivity segment by upgrading its “Dedicated Space” platform, a network that dedicates satellite bandwidth to individual aircraft. Notably, the company has reported 2x increases in download speed and 4x increases in upload capability on the 800+ aircraft equipped so far [7].

Key Takeaways

Despite its surface-level appearance, GEE’s distress can’t simply be attributed to COVID-19. Instead, it was driven by a poorly timed and debt-funded acquisition into a capital-intensive space. While revenue grew rapidly, the company’s debt grew even faster, with its ability to service this debt falling behind. The EMC acquisition serves as a great example of how poor capital allocation can be detrimental to a company’s balance sheet, despite being an industry leader.

Another lesson here is the inherent risk of rescue financing. While Searchlight’s investment provided much-needed liquidity and came with significant upside, it wasn’t nearly enough to carry GEE through a global pandemic, and ended up receiving little to nothing back, highlighting the shortfalls of injecting expensive debt into an already over-levered balance sheet.

Apollo’s emergence as the post-reorg owner also reflects a textbook loan-to-own execution. After entering the capital structure via secondary market purchases, the firm credit bid the full face value of its claim to acquire the company through a Section 363 sale, turning its claim into ownership without deploying additional cash.

GEE’s Chapter 11 gave the company a fresh start, cutting debt in half to $400mm and providing over $300mm of new money. The success of the rebranded entity, Anuvu, will depend on the company’s ability to adhere to its core strategy and stay disciplined with its capital allocation.

📚 Interested in our updated reading / wellness list? Check it out here.

🍰 Moving soon? Use our 10% discount for Piece of Cake, the mover of finance bros.

📈 Interested in buyside comp data? Access detailed compensation reports on buyside hub here.

👕 Interested in our merch store to shop our latest swag? Check it out here.

Sources (Available to paid subscribers only)

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Get Access to the Restructuring Drive

- See Sources and Backups to All Free Writeups

- Join Hundreds of Readers