Welcome to the 120th edition of the Pari Passu newsletter.

Following last week’s cryptocurrency post, today we will dive deeper into FTX’s bankruptcy that shocked the world in 2022 and is still discussed today. While not a standard bankruptcy in terms of its creditor base and valuation processes, FTX’s Chapter 11 shines a light on how the bankruptcy forum offers tools to navigate complex interests and corporate structures.

From the reasons behind financial distress, monetization strategies, and unexpected creditor recoveries, let’s dive deeper into what we can learn from one of the most influential bankruptcies of the digital era.

But First, a Message from Hebbia

Work a grind? It doesn’t have to be. Hebbia lets you do in minutes what used to take hours. Need to summarize a credit agreement or build a CIM? With Hebbia, you can do it faster than your MD can say, “This is what you signed up for.”

By automating repetitive tasks and synthesizing endless data into clear, actionable insights, Hebbia frees up PE / credit pros to focus on what they actually signed up for: making deals, growing companies, and maximizing returns (and avoiding Chapter 11).

Book a 20-minute demo to see why 1/3rd of the largest asset managers trust Hebbia.

A Brief Overview of FTX [1]

Co-founded in May 2019 by Sam Bankman-Fried (SBF) and Gary Wang, FTX was a global cryptocurrency exchange that offered a wide range of services like spot trading, future, options, and tokenized assets. It had more than one hundred subsidiaries of different types: FTX.com was the main exchange platform, FTX.US was the US-based exchange, Alameda Research was a trading firm and market maker, FTX ventures invested in crypto startups and blockchain projects, and foreign subsidiaries such as FTX Digital Markets operated in the Bahamas.

FTX quickly gained traction, first in the VC world. It would receive early VC funding from Binance, a top crypto exchange at the time. After a very successful Series B round in July 2021 that raised nearly $1bn from investors such as Lightspeed Venture Partners and Sequoia Capital, FTX was already sitting at an impressive $18.0bn valuation. In the following Series B-1 and C funding rounds, FTX would raise about $800mn in total, garnering further investment from firms such as BlackRock, SoftBank, and Paradigm.

In its peak of 2021, the company had more than one million users and was the third-largest cryptocurrency exchange by volume. By January 2022, FTX was valued at $32bn, a 77% increase from six months prior.

The Crypto Winter of 2022

As a quick recap of the last post, the crypto collapse started in May 2022 when the TerraUSD stablecoin collapsed. A stablecoin is a type of cryptocurrency designed to offer a stable value relative to another asset like the USD. One stablecoin is theoretically backed by one dollar, but this dollar soon decreased to $0.95. In reality, investors found out that there was no real collateral to support the price. As a result, the TerraUSD collapse wiped out $400bn of the $2 trillion crypto market cap.

This wasn’t just a collapse of one stablecoin – it was the start of a panic sell-off that spread across the crypto market. Hedge funds like Three AC heavily invested in the TerraUSD faced low liquidity and filed for Chapter 15 bankruptcy as they could not pay back a total of $3.5bn loans to crypto exchanges and lenders. Between November 2021 to November 2022, the prices of many crypto tokens plunged, including Bitcoin’s drop by 77.5%.

The Downfall of FTX

While FTX grew impressively within a few years, its downfall was quick and impactful as well. Months after the Terra-LUNA crash, crypto markets, although not fully recovered, have stabilized. Then, on November 2nd, 2022, SBF and FTX’s fates would change forever. For FTX, it was the November 2022 Coindesk article that raised concerns about Alameda’s insolvency. Behind the article was Coindesk’s senior reporter, Ian Allison, who was told by multiple sources to dig deeper into Alameda’s weak balance sheet even before the collapse of crypto platforms in early 2022[2].

Some key takeaways from the article were:

FTX and Alameda were not independent of each other. Despite countless interview questions regarding the conflicts of interests between the two companies, SBF had time and time again insisted that he was no longer an employee of Alameda and that the operations of the two companies were completely separate.

Alameda played a key role in the price regulation of FTT tokens, a type of token created by FTX, and offers discounts to FTT traders. In fact, Alameda held a huge portion of the available FTT pool and would regularly buy up huge amounts of the token to maintain FTT’s price when it dropped.

Alameda’s assets were greatly inflated. Although FTT was listed as an asset of the company, and a major asset at that, it could not actually be liquidated. This was because since Alameda owned so much of the available pool, it could not sell large amounts of FTT without its price completely crashing to zero. Therefore, the FTT that was used as collateral to borrow customer funds was essentially worthless as an asset.

Binance was an early investor in FTX, and it owned about 20% of the company. In July 2021, FTX bought back Binance’s $2.1bn equity stake in FTX, financed part in cash and part in FTT tokens. On November 7th, 2022, four days after the article was released, the CEO of Binance, a Canadian-Chinese entrepreneur named CZ, would announce on X that his company was liquidating its remaining $550mn in FTT, which was sold to them when FTX bought out their shares.

The announcement immediately sparked fear in the crypto space, and many FTX customers began withdrawing assets as they started doubting the reliability of FTX and crypto generally. The tweet alone generated an FTX customer bank run. To stay afloat during this emergency, FTX would begin negotiations with Binance on November 7th to complete a strategic acquisition of FTX by Binance. However, when Binance analysts began their due diligence processes on FTX, they were unable to complete the deal. FTX’s poor accounting practices and abysmal balance sheet made it impossible for the analysts to gain any kind of understanding of FTX from a financial perspective. Within 72 hours, FTX faced a total of $6bn in customer withdrawals, which drove down the price of FTT by 77% from $22 to $5 per token. FTX ended up halting the withdrawals, but the damage had been done: the decline in token prices directly eroded the asset value on the balance sheet.

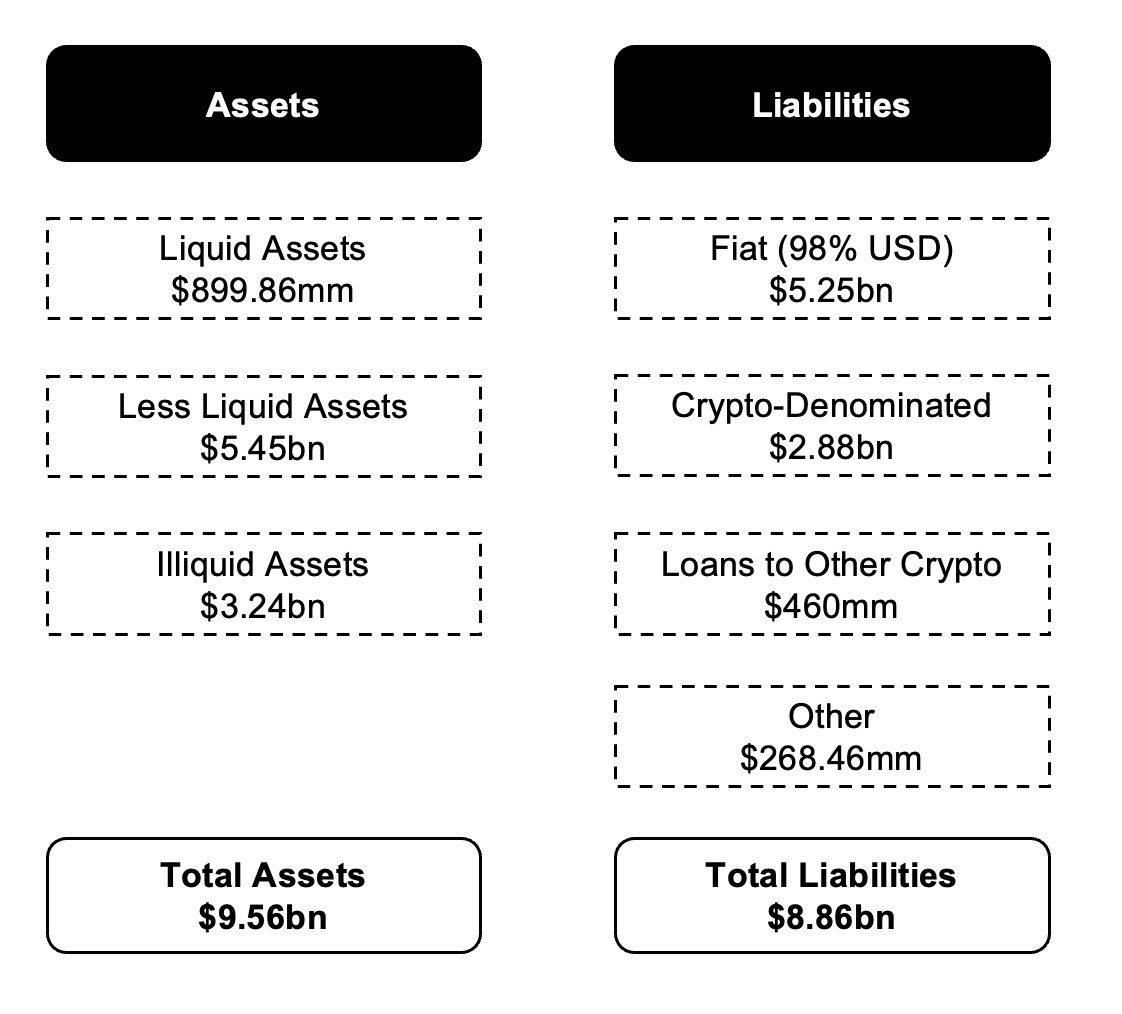

To assess the level of financial distress for a crypto exchange, we have to look beyond income statement metrics. In 2022, FTX’s operating income was projected to drop by 63% to $144mm while the revenue was projected to increase by 10% to $1.1bn as the exchange offered discounts to attract many users. These income statement figures did not fully capture FTX’s declining financial health. What really had been overlooked by the market was the problematic balance sheet. On November 8th, a Financial Times article leaked that FTX only had $900mm in assets compared to $9bn in liabilities. While adding less liquid and illiquid assets would lead to $9.59bn total assets, we will focus on the liquid $900mm assets as they truly represented what FTX was worth. For crypto exchanges, customer deposits are considered both an asset and a liability. They hold customer deposits but owe it to their customers. For an exchange to be solvent, liquid assets should exceed customer deposit liabilities to meet customer withdrawal demands [20].

The problem: only customer deposits in fiat currency (USD, EUR) were recorded as assets and liabilities. Since the customer deposits in crypto were not recorded, assets and liabilities were significantly understated. If the crypto deposits had been recorded as assets, customers would have easily noticed the $4.1bn of FTT transferred from FTX to Alameda, which will be elaborated in the next section [21].

Another problem: in total, FTX misused $10bn in customer deposits and corporate funds in the form of cash and stablecoins, leading to a severe liquidity shortage of $8bn (gap between $900mm assets and $9bn liabilities). However, these transactions from FTX to Alameda were never recorded on the balance sheet to avoid the scrutiny of regulators. Since only $9bn in liabilities were initially recorded, the balance sheet understated true liabilities by at least $4.1bn of hidden funds to Alameda [22].

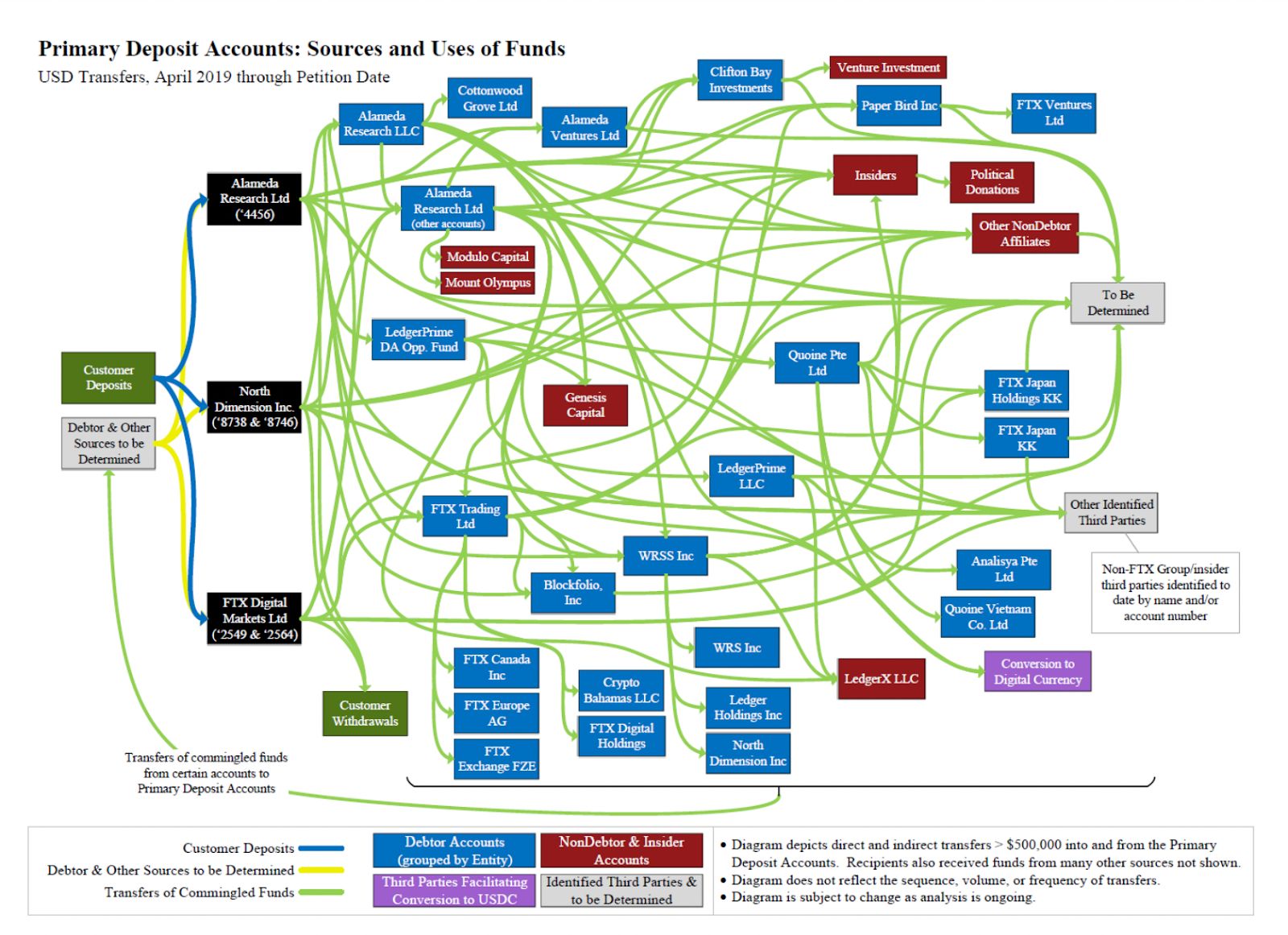

On the assets side, customer deposits in crypto tokens were not recorded on the balance sheet. As a result, on the liabilities side, the balance sheet did not reflect loan payables to many other customer accounts and third parties (blue, red, grey boxes in Figure 2 below), resulting in an estimated range of true assets and liabilities between $10bn and $50bn.

Figure #1: FTX Leaked Balance Sheet Breakdown [3]

All this time, FTX was able to get away with this balance sheet because the value of tokens was artificially inflated (as explained below). Another reason was that the balance sheet didn’t need to be balanced. As a private company, FTX never had to audit or release its financial records publicly. Under SBF’s trustworthy public persona, investors, regulators, and customers never questioned FTX’s financial health.

Most concerning was the percentage of assets consisting of highly illiquid tokens like FTT and Serum, which declined in value by 91% and 60% in one week, respectively. Similar to FTT, only 3% of Serum was publicly traded while 97% was held by FTX. Big problem: Serum was made up by FTX – it only traded mostly within the FTX exchange. So if FTX ever decided to sell Serum in the open market, it would flood the market with too much supply compared to the demand, dropping the prices significantly.

Although not all assets were created by FTX, only $900mm out of the $19.6bn in total assets were cash or liquid (easily convertible to cash) stock and cryptocurrencies. All this time, customers had faith that FTX could easily pay them back. But in the end, it turned out that assets were only one-tenth of reported liabilities [3]. More importantly, where did all this money go?

Simply put, there are a few reasons for FTX’s failure that will recur throughout the post, including:

Absence of corporate governance: there were no third-party investors on the board and all decisions were in the hands of a group of inexperienced, unsophisticated individuals.

Control failures: financial statements were either non-existent, limited, or completely unreliable. Assets and liabilities were shuffled among the subsidiaries and insiders without proper documentation, such as sending customer funds to Alameda without customer consent.

Use of native tokens as collateral: FTT was used as collateral for Alameda’s trading activities, but this was highly risky since the value of FTT was dependent on the market’s perception of the FTX and the token’s future value. A simple analogy would be: the crypto token is the stock for FTX, the company. If FTX generates strong profits, the token’s value will rise.

High concentration of illiquid assets: a lot of FTX’s tokens had low trading activity and would result in low valuation under liquidation.

Poor Cybersecurity: Ignoring security controls, FTX put all their assets in “hot wallets,” which are less secure online cryptocurrency wallets used for conveniently managing digital assets. On November 11th, 2022, A group of hackers stole $477mm worth of cryptocurrency stored in FTX using a service called ‘mixers’ that hid their traces across the blockchain network. The hacked money represented 15% of the total $3.1bn owed to the largest creditors [4].

Where did my money go? FTX’s Commingling of Funds [5]

What makes FTX’s bankruptcy particularly interesting is that it wasn’t simply about splitting up the pie of fixed assets – the main objective among lenders of a distressed company. The debtors not only had to locate lost assets but also understand how much could be recovered.

Without clear intercompany loans between subsidiaries, assets and liabilities traveled through different entities without proper records. The graphic below may look complex, but there are a few main avenues where the $10bn of customer deposits and corporate funds were ‘commingled’ by SBF and other directors, meaning they were used for unrelated purposes.

As a customer of FTX, you would want your funds to be stored safely or only used for trading. However, these were transferred to bank accounts (the black boxes) of Alameda Research, a subsidiary called North Dimension, and FTX Digital Markets, a non-debtor subsidiary that was solvent. Here, FTX clearly breached its fiduciary duties. They used their customers’ money for Alameda’s general corporate purposes, speculative trading, venture investments, purchase of luxury properties, and political donations to bolster FTX’s status. Then, the customer funds flowed into various debtors’ wallets (the blue boxes) across various jurisdictions. In some cases, they would end up in the gray boxes in the hands of third parties with the value to be determined.

Figure #2: Visual Depiction of Commingling of Funds [5]

A transfer with a significant impact on customer recoveries was transferring FTT, FTX’s native cryptocurrency, to Alameda Research. By June 2022, the Coindesk report revealed that 163mm FTT tokens with a market value of $4bn were secretly transferred to Alameda. As a quick recap from the crypto post, FTX had a feature called spot margin trading that allowed users to borrow funds from other users. Just like a traditional loan, users would pay principal and interest. For example, if the leverage was 10x, users could put down $100 of their money to make a $1000 trade. Before regulators stepped in to bring down maximum leverage to 20x, users were allowed to trade at leverage as high as 101x. To fund their trades, Alameda took out loans from different crypto lenders like Genesis and Voyager Digital, with customer funds in cash or FTT as the collateral backing these loans.

Making trades with FTT gave the false impression that the token was in high demand, so Alameda could continuously borrow more funds. In reality, there was little value to the tokens. When collateral is a tangible asset like real estate, lenders have more certainty about the real value of the assets. The problem was that FTT was not a reliable source of collateral – it did not adequately capture the risk behind the FTX exchange or any liabilities on FTX’s balance sheet. Key point: the value of FTT was directly correlated to the market’s perception of FTT’s future demand. But if FTX collapses, how would FTT exist? When the market lost confidence in the stability of FTX, FTT prices declined by 75% in one day and automatically triggered a liquidation of customer loans, meaning FTT was sold off in a fire sale. Within five days, FTT’s market value was wiped out by 90.5%, from $2.94 trillion to $281bn. As panic rippled through the market, customers holding the top six crypto tokens withdrew a total of $20.7bn across the crypto exchanges between November 2nd and November 13th, 2022 [19]. Specifically, users on FTX withdrew at least $5bn worth of crypto tokens. Firstly, this meant that true liabilities on the balance sheet would have been at least $14bn (from the existing $9bn, which did not include crypto deposits as explained above). Secondly, customers could still withdraw less liquid crypto tokens ($5.5bn as recorded above) since this was just moving their tokens to external wallets. However, beyond this, FTX could not meet withdrawal demands and froze customer accounts.

The possibility of monetizing FTT looked dim. Having a separate balance sheet from FTX, Alameda held around 25% of their $14.6bn assets as unlocked FTT tokens. $292mm out of $7.4bn in liabilities were in locked FTT tokens. Intuitively, listing tokens as an asset would make the most sense since Alameda can freely sell the tokens in the market for profit. However, locked tokens were treated as a liability as they could not be monetized to pay back customers. Locked tokens are contractually prevented from being traded freely in the market for a period of time, so they have little ability to boost FTX’s liquidity. Any future unlocking would suddenly increase the supply and drive down FTT’s market price. Similarly, unlocked tokens could contribute very little, given FTT’s market value already declined heavily after FTX’s bankruptcy [6].

This left customers unable to withdraw their funds as FTX and Alameda did not have enough liquidity. Furthermore, they have never agreed to be exposed to Alameda’s risk. Naturally, customers demanded that they should be first in line to receive any returned funds. Where the tension rose in court, however, was customer creditors demanding a senior position in the capital structure. More discussion between the two competing creditor groups will come below.

Without the funds to pay back its customers and with no one to bail it out, FTX filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the District Court of Delaware on November 11th, 2022. Total liabilities were $7.8bn based on the unaudited balance sheets prepared by SBF. But based on the petition filing, both assets and liabilities were about to look much higher at an estimated $10bn-$50bn as the new debtors stepped in to uncover the missing figures.

The Critical Role of New CEO John J. Ray III [7]

Before SBF was arrested and extradited to the U.S. on December 12, 2022, John Ray stepped in as the new CEO on November 17th, 2022, to navigate FTX through bankruptcy. As a restructuring veteran, Ray tried to use Chapter 11 to achieve five goals: implement controls, protect and recover assets, conduct transparent investigations, efficiently coordinate with any non-US proceedings, and maximize value. The top priority for John Ray and the debtor’s advisers was reorganizing the corporate structure and building an accurate balance sheet.

“I have over 40 years of legal and restructuring experience. I have been the Chief Restructuring Officer in several of the largest corporate failures in history…Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here.”

– John J. Ray III

Cleaning Up the Corporate Structure with ‘Silos’ [8]

Many companies operating in different segments often have multiple or even dozens of subsidiaries. In the debtor’s case, they were operating…

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)