Welcome to the 137th Pari Passu newsletter.

Today, we’re looking at a different kind of software bankruptcy in which the core business wasn’t the problem, but the funding model was. EyeCare Leaders was sponsor-backed, but not by a PE firm. Instead, the company was funded through insider loans from life insurers controlled by Greg Lindberg, a now-convicted insurance mogul. When those insurers were placed into rehabilitation in 2019, the company lost access to capital and spent the next four years slowly unraveling.

This deep dive explores how the provider of electronic health record software to over 8,000 eye-care practices files for bankruptcy with no third-party debt. We’ll walk through the regulatory landslide that froze its capital structure, the critical mistakes that followed, and the insider-backed DIP financing and 363 sale that returned ECL to the insurers that created the mess in the first place.

When things fall apart — Private Credit enforcement from New York to Hong Kong

The global private credit market is exploding, projected to nearly double by 2028, but this rapid growth hides rising distress in larger facilities. With increasing default risks, traditional strategies are failing, forcing lenders into legal action to maximize recovery.

Join 9fin on July 10th at 10 a.m. ET for a webinar on private credit enforcement. Hear from leading experts including John Han (Kobre & Kim), Dan Zwirn (Arena Investors), Ron Thompson (Alvarez & Marsal Asia), Max Frumes (9fin) and others. They'll provide essential insights into global enforcement actions, triggers, and the actual tactics used. Learn what lenders truly recover, and what's lost by not acting. This session equips you to identify when to act and navigate complex legal landscapes to protect your investments. Don't miss these critical insights!

Eye Care Leaders Overview

Eye Care Leaders (ECL) was founded as a one-stop shop, providing software solutions for optometry and ophthalmology (eye-care) practices. The company was born as a rollup-style strategy by Greg Lindberg, a North Carolina insurance tycoon. Lindberg used Global Growth (f.k.a. Eli Global), which had no limited partners and was funded with capital from his insurance businesses via “intercompany loans”, to buy up software providers in a fragmented eye-care software market. Some of Lindberg’s insurance companies included Colorado Bankers Life Insurance Co., Bankers Life Insurance Co., and Southland National Insurance Corp. Lindberg made dozens of acquisitions during the 2010s in spaces such as healthcare, software, education, and finance. The ECL umbrella was specifically comprised of software offerings for Optometrists and Ophthalmologists [1].

To quickly clarify, Optometrists (ODs) examine, diagnose, and treat patients' eyes; they are who you’d think of as a general eye doctor, treating general vision problems and prescribing things like glasses and contacts. On the other hand, ophthalmologists (DOs) are medical doctors who treat complex eye diseases and perform eye surgeries. You’d typically find ODs in retail optical chains, private offices, clinics, and select large retailers. You’d find DOs in hospitals, surgery centers, and specialty clinics. While ECL served both ODs and DOs, ophthalmologist practices, which are more lucrative customers, accounted for the majority of ECL's revenue.

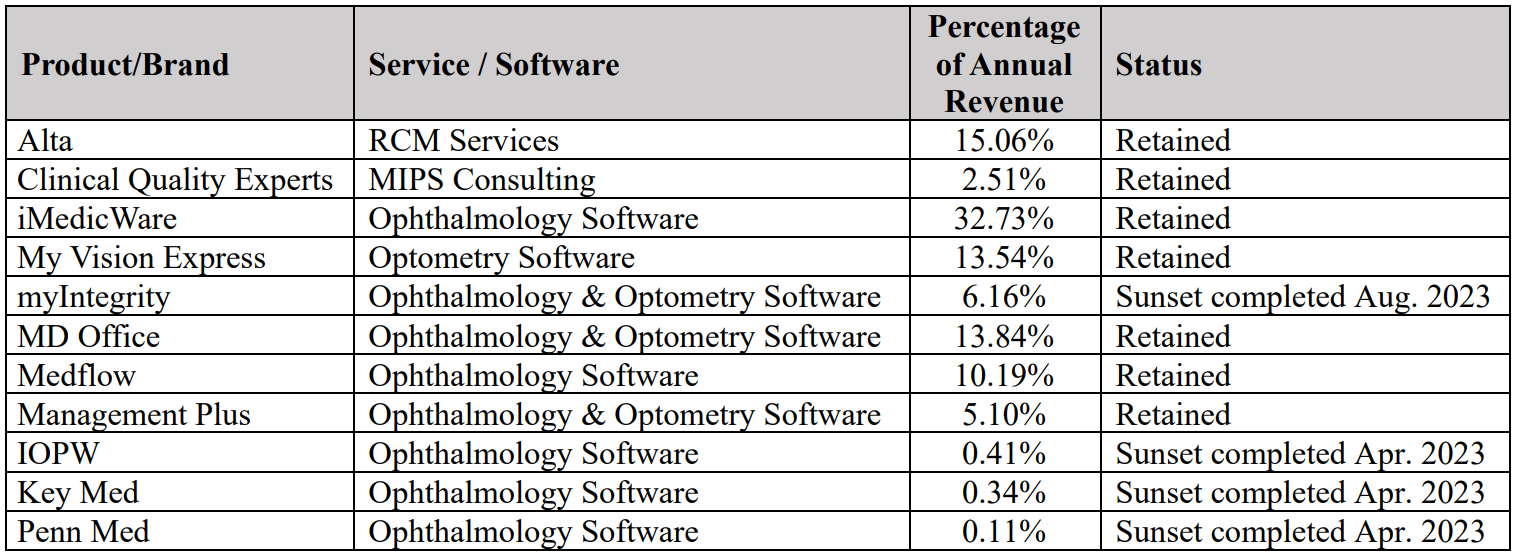

The company’s software portfolio featured notable names, including iMedicWare (ophthalmology software), My Vision Express (optometry software), and Alta (revenue cycle management software). Collectively, these three products accounted for roughly 62% of ECL’s annual revenue. The company offers cloud-based electronic health records (EHR), practice management, revenue cycle management, and some consulting services. The table below details all of ECL’s offerings [2].

Figure 1: ECL Segments as % of Annual Revenue [2]

ECL’s primary offerings were software and revenue cycle management (RCM) services. The software segment was split between electronic health records (EHR) and practice management (PM), with PM usually being bundled with EHR, creating a full-suite software platform.

Electronic Health Records (EHR): ECL’s cloud-based EHR system was designed to replace paper charts and on-site servers. EHR software stores and manages clinical data such as exam notes, diagnoses, surgical plans, imaging results, etc. ECL’s EHR offerings, with IMedicWare (IMW) and My Vision Express (MVE) being the two largest, presented themselves as secure cloud-based alternatives. ECL charged monthly license fees per provider for access to the software, along with support services and updates. The company charged much more for iMedicWare ($3500 for IMW vs $300 for MVE per provider per month) as software for DOs must be more technical, supporting surgery, imaging, and complex charting [1].

Practice Management (PM): ECL also offered PM software to assist with the day-to-day operations of eye-care practices. PM includes things like appointment scheduling, patient check-ins, insurance verification, and coding. In healthcare, coding is the process of attaching specific billing codes to services provided. ECL typically bundled the PM services with its staple EHR offerings [1]. This strategy lowered churn, as practices would struggle to switch software providers when so heavily integrated with ECL products.

Revenue Cycle Management (RCM): Alta Billing was ECL’s primary RCM company. Unlike other offerings, the company’s RCM segment was service-based, allowing Alta to provide billing services for the practice from claim creation to reimbursement. The revenue cycle in healthcare is quite complex, and it’s good to have a baseline understanding of the process, so let’s simply outline the different steps. First, after a patient visits, clinical staff assign the standardized codes we mentioned above. Procedure codes determine what treatment was provided, and diagnosis codes determine why it was provided. These codes create a claim, which is submitted to the patient’s insurance provider. The insurer then approves, denies, or partially reimburses the claim. Alta handled this entire process for its RCM clients, for fees of roughly 6% of clients' net collections [1].

ECL grew rapidly to serve over 8,000 ophthalmology and optometry practices, roughly a third of the U.S. eye-care market by location count. Additionally, ECL managed records for over 25 million patients at its peak [1]. While ECL’s financials are not public, we can use some information available to estimate its peak run-rate annual revenue. In the class action suit against ECL, which we’ll cover momentarily, the numbers in the table below were reported:

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Get Access to the Restructuring Drive

- See Sources and Backups to All Free Writeups

- Join Hundreds of Readers