Welcome to the 125th Pari Passu Newsletter,

After a very successful retail bankruptcy deep dive last week, today we are looking at a more technical topic: equitable subordination.

In almost every bankruptcy, one party tends to blame another for some issue. Whether it relates to predatory lending practices or poor management, stakeholders strive to remedy their own claims by asserting the wrongdoing of the other party. Today, we are covering a less well-known aspect of the Bankruptcy Code: Equitable subordination, which allows the courts to reorder claims in the event of a bankruptcy if wrongdoing is present. While this is a powerful legal tool, implementing it effectively is tricky, and much discretion is left to the courts.

This report details equitable subordination, what’s required to subordinate a claim, and some key limitations. We’ll also cover the fascinating case of LightSquared, where two billionaire investors fought over the hottest telecom assets at the time, and even after one party had its claim subordinated, the results may still surprise you. Let’s get into it.

Equitable Subordination Overview

As we’ve outlined before, Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code allows distressed companies to reorganize their operations instead of liquidating in order to capture more value for creditors and continue to operate as a going concern. A foundational principle of bankruptcy is the absolute priority rule, which dictates the order in which claims are paid out, ensuring senior creditors are paid out first. Almost all of the time, the absolute priority rule governs the remedies outlined in a restructuring solution. Unfortunately, there are times when creditor misconduct occurs, and the court must intervene to ensure an equitable distribution of claims for every creditor involved. In certain situations, the bankruptcy court may need to alter the order in which claims are paid out, which leads us to equitable subordination.

Equitable subordination is a powerful remedy within the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, outlined in section 510(c)(1), that allows the court to effectively reorder the priority of specific claims among creditors. The primary purpose of equitable subordination is to ensure fairness in the bankruptcy process when wrongdoing is present. Suppose a creditor acts in a way that is inequitable, resulting in injury to other creditors or giving themselves an unfair advantage. In that case, the court may subordinate all or part of the creditor’s claim to remedy the situation. The ultimate goal of section 510(c) is to provide a result that returns creditors to the position they would have been in had misconduct not occurred [1]. Equitable subordination is not meant as a punishment for wrongdoing; instead, it is simply in place to protect creditors who acted in good faith.

History

The concept of equitable subordination has been around long before it became part of the Bankruptcy Code in 1978. Prior to this, the courts simply relied on the interpretation of equitable principles outlined in the common law. In Pepper v. Litton (1939), the Supreme Court ruled that bankruptcy courts have the power to disallow or subordinate claims if equity and fairness require doing so, especially when the claim being subordinated is an officer, director, or stockholder [2]. This ruling set the stage for what we currently see in section 510(c) of the Bankruptcy Code.

Legal Standard for Subordination

Today’s bankruptcy courts rely on the case In re Mobile Steel Co. (1977) to determine whether Equitable Subordination is appropriate and warranted. This case establishes the three-part test [1]. Under the three-part test, the following three conditions must be satisfied for the court to subordinate a claim:

Inequitable Conduct: The claimant (insider creditor) engaged in some form of misconduct or wrongdoing. This can include fraud, breach of fiduciary duty, or simply unfair behavior. An example might be a predatory loan issued by a company officer.

Injury or Unfair Advantage: Second, the conduct must harm other creditors or leave the claimant with an unfair advantage. Most often, this involves unfairly skewing the distribution of claims to the claimant’s benefit. If the insider loan above strains liquidity and forces the company to file, it would clearly harm other creditors, especially those below it in the capital structure.

Consistency with the Bankruptcy Code: Lastly, the subordination of claims must not interfere with any other aspects of the Bankruptcy Code, ensuring fairness for all creditors. This means that even if misconduct was present, creditors still have protections. Specifically, claims that the Bankruptcy Code elevates explicitly, such as administrative expenses, wage claims, or tax claims, can not be pushed below general unsecured claims. For example, it would be much more challenging to subordinate a DIP claim because post-petition DIP financing is treated as an administrative expense under Section 364.

As you can see, the three-part test leaves a lot on the table regarding a court decision, and the bankruptcy court has much discretion when determining whether conduct is inequitable and worthy of reorganizing claims.

Insiders vs. non-insiders

When it comes to the discretion left to the courts, a significant consideration is whether the claimant is an insider creditor (majority shareholder, affiliated entity, sponsor, corporate officer, etc.). Insiders are subject to higher levels of scrutiny when considering misconduct. Insiders’ lower threshold for Equitable Subordination arises from insiders having a fiduciary duty, which is the legal obligation to act in the best interest of their shareholders. Because of this, misconduct by insiders is often viewed by the courts as more egregious due to it being a breach of fiduciary duty [1]. Additionally, because insider creditors control a company, there is much more room for misconduct and asset manipulation to skew recoveries in a distressed situation.

However, the Bankruptcy Code does not explicitly state that Equitable Subordination may not be applied to outside creditors. Still, due to their removal from the company's operations, the threshold for a ruling against them is often higher. For an outside creditor to be subordinated, there must be egregious conduct, such as fraud or gross overreach, as outside creditors also do not bear the fiduciary duty that insiders do. Our case study will outline a situation in which an outside creditor’s claim was subordinated.

Hypothetical Examples of Creditor Misconduct

Now that we’ve established the criteria for subordination and who it often applies to, let’s look at some common scenarios that may be grounds for equitable subordination.

Predatory Lending: A creditor imposes exploitative terms upon the debtor. These terms can include unreasonably high interest rates or strict repayment terms, typically done with the intent to cause the debtor to default and give the creditor access to assets or control of the company. Because the creditor isn’t technically deceiving the debtor, these predatory lending practices would have to cause extraordinary harm to other creditors to be grounds for equitable subordination. While in theory, a distressed debtor could walk away and refuse unreasonable terms, it may be so desperate for liquidity that it accepts predatory financing as an alternative to running out of money. Moreover, if the lender holds a coercive position over the debtor, the threshold for misconduct becomes even lower.

Fraud: A creditor deliberately deceives the debtor and/or other creditors by providing false information, misrepresenting terms, etc., tricking stakeholders into an unfavorable transaction. For fraud to be considered fraud, it must be intentional deceit. Fraud is typically considered more egregious and thus more likely grounds for equitable subordination.

Insider Abuse: An insider creditor breaches fiduciary duty by putting its needs above the company's interests. This may include self-dealing practices, where the insider forces the debtor into loans at unfavorable terms. It might also include abuse of confidential information or any other insider activity deemed a breach of fiduciary duty in bad faith.

An important emphasis is that these examples aren’t guarantees of equitable subordination. The right conditions - and the right judge - must be present for a claim to be subordinated, and the solution must not interfere with any other principles of the Bankruptcy Code.

Simple Subordination Example

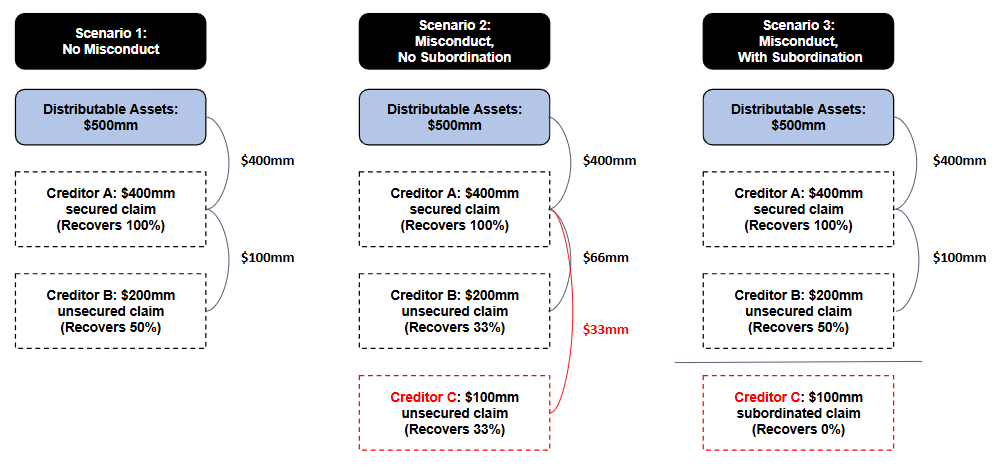

Before we continue with the post, let’s go over a simple example of what recoveries would look like under a few different scenarios:

Scenario 1: Company ABC files for bankruptcy with $500mm of total assets. The capital structure contains Creditor A with a $400mm secured claim and Creditor B with a $200mm unsecured claim. In this scenario, there is no misconduct from insider creditors. Some simple waterfall math would leave Creditor A with a 100% recovery and Creditor B with a 50% recovery. Remember that secured creditors must always be paid out first, so Creditor A would receive its full $400mm claim, leaving only $100mm left for Creditor B’s $200mm claim.

Scenario 2: Company ABC files for bankruptcy with $500mm of total assets. However, the capital structure now includes an additional $100mm unsecured claim from Creditor C, an insider creditor. The court eventually found that Creditor C, a majority shareholder, forced Company ABC into taking the $100mm loan at an unreasonably high interest rate (self-dealing), forcing the company into distress and breaching fiduciary duty. Despite the misconduct, the bankruptcy court did not deem the misconduct severe enough to subordinate Creditor C’s claim. In this case, Creditor A still receives its entire $400mm, but Creditors B and C must share the remaining $100mm because they are both unsecured. Therefore, Creditor A receives a 100% recovery on its secured claim, and Creditors B and C each receive 33%. As you can see, Creditor B, an innocent creditor, is worse off following Creditor C’s misconduct.

Scenario 3: Assume the same capital structure and misconduct as scenario 2. However, this time, the court decided that Creditor C’s wrongdoing passed the three-part Mobile Steel test. The court chooses to subordinate all of Creditor C’s claims. Under this scenario, Creditor A recovers 100%, and Creditor B recovers 50%, which are the same recoveries had Creditor C not engaged in predatory self-dealing. In this case, Creditor C receives zero recovery.

Equitable subordination is not punitive, meaning it isn’t meant to punish the creditors at fault. Courts carefully calculate the minimum amount to be subordinated to remedy injury. For example, if there were distributable assets of $650mm, the courts would only need to subordinate 50% of Creditor C’s claim for Creditor B to recover 100%. In that case, Creditor C would recover 50% instead of zero. There are no fines or damages part of equitable subordination. While it may seem like it’s meant to punish wrongdoing, courts only subordinate the extent necessary to provide other, innocent creditors with their original recoveries.. Figure 1 below outlines this scenario.

Figure 1: Hypothetical example of equitable subordination

Let’s apply the three-part test to this scenario:

Subscribe to Pari Passu Premium to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Pari Passu Premium to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- Get Full Access to Over 150,000 Words of Content

- Institutional Level Coverage of Restructuring Deals

- Join Hundreds of Readers

- Exclusive Premium Writeups (Starting April 2025)